I spent four days in Jaipur last month. It was my first time in the city—I’d always wanted to visit, but I made this trip with a very specific plan in mind. Instead of touring the forts and palaces, I confined myself to the resplendent Hotel Diggi Palace, which has hosted every edition of the Jaipur Literature Festival since it was started in 2006. (In addition to the Palace, I spent a large part of my time at India Coffee House eating mutton dosas, and an even larger part at the bookstore.)

‘This was my first literary festival ever, and already, I was lightheaded and buzzing with an as yet unrequited excitement.’ Photograph by Krishna Kulkarni.

The Jaipur Literature Festival is the largest free literature festival in the country. To be honest, being my first time, I expected it to be a beautifully decorated, enormous space, full of literary giants who would be watched by an audience of no more than a hundred people. Surely, this is not the sort of event that would draw crowds, I thought naïvely, and somewhat foolishly. My first day (January 22) was a huge surprise. I wouldn’t be exaggerating if I said that I had never seen crowds like that before or since (but I’ve never been to the NH7 Weekender). I made my way through thousands of people, each of them with a programme in one hand and a book in the other. Everywhere I turned, I overheard snippets of conversations about literature, politics, writing, each one more interesting than the last. I was in heaven. This was my first literary festival ever, and already, I was lightheaded and buzzing with an as yet unrequited excitement. I missed the first day of the festival, and hence, the keynote speech, on account of some poor planning on my part, but I was adamant about making up for it on the second day. Early in the morning, I sat on my bed with the programme and a pen, marking the panels and seminars I wanted to attend, making sure that none of them overlapped with one another. Fortunately, on that day, none of them did.

The Jaipur Literature Festival, like many other music and literary festivals, contains several ‘tents’ within a single, larger venue—in this case, Hotel Diggi Palace. This meant, regrettably, that there were a number of events occurring simultaneously throughout the day. Of course, this is the only practical way to do it—one can only imagine how long the festival would run if the events were lined up linearly, one after the other (about a month, after some quick math), but this system makes some difficult choices necessary, which I’d rather live without.

I began the fest with Margaret Atwood. She spoke about her new book, The Heart Goes Last, about love in a dystopian world (which is her modus operandi, for those who know and love her). She was interviewed by an ex-protegé of hers, Naomi Alderman, who has a couple of bestsellers on the shelves now herself. The conversation was stimulating, even though I failed to acquire a seat and therefore had to stand through it. They spoke about the process of writing (Stephen Fry, in a later interview, hit the nail on the head when he said that the number one thing everyone at a literary festival is interested in is process). This was immediately apparent with the questions raised at Atwood’s seminar: she was asked many a question about ideation, how long she takes to write, and was showered with a great many well-deserved platitudes. I was itching to ask her about her poetry, which no one seemed too concerned with, but I wasn’t offered the microphone in time. Someone did, however, ask her how she felt about the ‘failure of feminism’, which incited a witty, biting, and most Atwood-like response. She took a quick vote. “Anybody who thinks women should not be educated, raise your hands,” she said. She then continued to question the audience about voting rights, whether or not they thought “women should be considered humans” and whether women should be forced to wear corsets. No hands were raised. She turned to the poor guy who asked the question, and informed him, in no uncertain terms, that feminism has not failed. There was a burst of delighted applause, and the discussion came to an end.

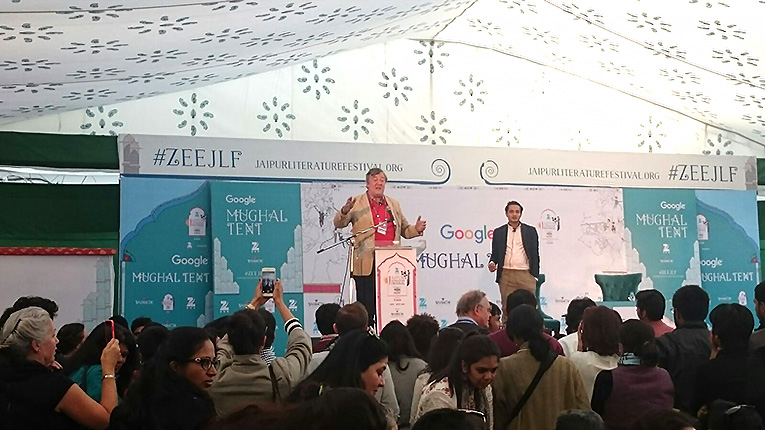

‘I stood in line for a good forty minutes to get my book signed by him, and when I was finally in his presence, I was unable to utter a single word.’ Photograph by Krishna Kulkarni.

The next panel I watched was titled ‘Selfie’, and was about autobiographies. I attended the discussion to watch Stephen Fry (whom I adore), but ended up rather falling in love with the rest of the panel as well. They spoke some more about process; about the need to write an autobiography, whether or not it’s some sort of narcissism, how much of your friends and family to write in (the very things we all wonder about when reading them). The discussion was engaging and stimulating, and I was particularly taken by Helen Macdonald’s H Is For Hawk, in which she chronicled her experience as a falconer, which she used to cope with her father’s death. On the morning of January 24, I watched her being interviewed about it, and she read a passage aloud for the audience. The prose was glittering, and I instantly liked the book. I made a mental note to buy it, but much to my regret, forgot to do so. Stephen Fry talked about his comprehensive, three-part autobiography in this session, and about the second part of The Fry Chronicles in greater detail the following morning. He played the crowd like Shakespeare’s Antony. A perfect Rowan Atkinson impression, some wonderful Hugh Laurie anecdotes, plenty of well-placed literary references, and he had us all swooning. It made perfect sense, then, that his speech that afternoon (January 23) about Oscar Wilde was packed. I adore Wilde, and mouthed along to the anecdotes, as though I was at a literary rock concert, and at the end, I stood up and applauded Fry like everybody else. I stood in line for a good forty minutes to get my book signed by him, and when I was finally in his presence, I was unable to utter a single word. I shook his hand, thanked him, and watched as he waved his hand across the page and a signature appeared. I turned to look at the line snaking behind me and realised that he has, if this is at all possible, won the J.L.F. I was unable to attend individual talks by any of the other speakers on the ‘Selfie’ panel, although I was quite eager to read their autobiographies as well.

‘Hunt and Tharoor, both highly politicised and esteemed historians, quickly became representatives of their own empires’ histories.’ Photograph by Krishna Kulkarni.

Sarah McPhee spoke about her book, Bernini’s Beloved, which is about representations of jealousy in Renaissance Roman art. She painted the most human picture I have seen painted of Bernini, and I learnt a great deal. This was one of many historically themed books and lectures at the forefront of the festival this year. Another example of this was Gerard Russell’s Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms, about which he was interviewed by William Dalrymple (my first and only encounter with the man during the festival, apart from a brief hello at the entrance on Day 1), on the morning of the 25th. The biographers panel turned out to be quite historically driven as well—there were biographies about spies (Ben Macintyre’s Kim Philby book), politicians (Victoria Glendinning’s Raffles), and economists (Tristram Hunt’s Engels). There was an air of academia about the biographers panel as they spoke about reconciling painstaking research with creative liberty, and about biographies as a part of history. As a lover of the biography as a form of writing, I took great pleasure in the discussion, as I did in the historicity that pervaded the festival. The political married the historical when Tristram Hunt replaced Niall Ferguson as the interviewer for Shashi Tharoor on January 25, and the discussion turned to colonialism and artefact ownership. Hunt and Tharoor, both highly politicised and esteemed historians, quickly became representatives of their own empires’ histories. The audience loved Tharoor, but it was Hunt, in my opinion, who really triumphed, playing his cards with the objectivity of a historian and the patriotism of a politician, acing Tharoor, who seemed more of a politician than anything else.

The highlight of the festival, however, was when history, politics, and literature combined in the form of James Shapiro, a professor of Shakespearean studies and a personal hero of mine. He came in on the morning of the 24th to speak about his new book, 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear, which he followed with Shakespeare in America, tracing Shakespeare’s presence in some of the greatest historical moments in the country’s history. I met him after the lecture, and professed my love for his work. He was very indulgent, and as he signed my book, I was struck by how surreal this moment was: only a few months ago, I was poring over his papers for my M.A. dissertation in the seclusion of my room.

Now, as I revisit my experience, I’m suddenly full of little regrets. I wish that I had seen Irving Finkel and some more of Dalrymple, that I had reached a day earlier and been there for the keynote speech, that I should have bought H Is for Hawk like I wanted. But more than anything, I think about the magic of literature festivals; about how they bring people and ideas together so seamlessly, and I feel at peace.