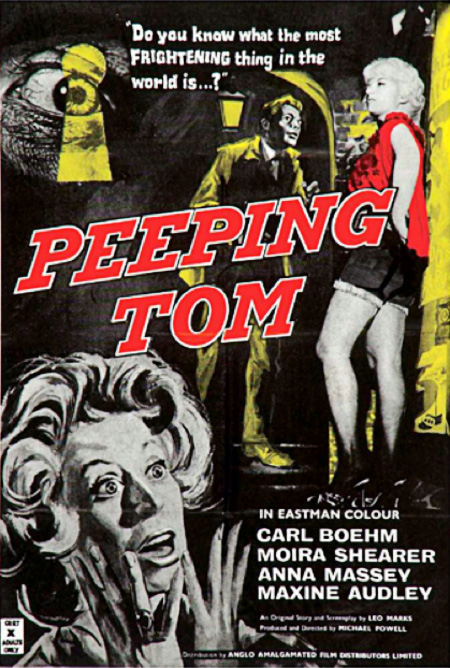

Jumping from A Clockwork Orange which works on an indexical and direct presentation of voyeurism, we move to Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), which is submerged in dealing with how cinema is a powerful medium because it addresses the most intimate in you and yet it’s a public form.

Peeping Tom is about a serial killer who uses his movie camera as a weapon: It’s equipped with a stiletto and a distorting mirror. He simultaneously kills and films women, showing them their own fear in the reflection of their screaming faces. Peeping Tom effectively ended Powell’s career. Powell’s sinister masterpiece was trashed by British critics—“The only really satisfactory way to dispose of Peeping Tom,” wrote London Tribune‘s critic at the time, “would be to shovel it up and flush it swiftly down the nearest sewer. Even then the stench would remain.”

Peeping Tom was about porn and how it is a flourishing industry along with the “respectable” movie and newspaper industry.

In the beginning of the film, as Mark watches in silence at the black and white projection in the darkness, of the walk upstairs by the prostitute, the disrobing and the look of horror by a curious light in the eye, he seems to get up uneasily from his chair as if experiencing an anxious orgasm. The film was considered nasty because of the apparent fetishisation of all the women in the film by Mark. As sexual politics becomes important during this time, patriarchal images and ideology come under attack and is linked to everything that is wrong with cinema and visual culture.

Hitchcock’s cinema comes under attack and is used to mobilise such debates about family, domesticity, work, and sexuality. Feminist film critic Laura Mulvey makes a polemical argument about how the male gaze engages with the cinematic gaze-overlapping of masculine point of view with the cinematic apparatus, and that pleasure of looking has been split between active/male and passive/female, where the woman is never the bearer of the look and is known for only her “to-be-looked-at-ness”. However, to call the film sexist is a sign of really essentialising a lot of elements. In fact, the two most important women in the film—Mark’s tenant Helen (Anna Massey) and her blind mother (Maxine Audley)—play active roles, and each takes the initiative in entering Mark’s life.

The central underlying theme of Peeping Tom is voyeurism.

What is really wrong with this debate is it is too prescriptive and anti-pleasure hinging on a form of ‘Christian morality’, where visual forms have been given too much importance in order to see how they are constructing spectators. But what this theory really misses is that there is no concept of a universal spectator. Therefore, whether a female viewer can feel complicity with Mark is a redundant argument. In fact what Powell really wanted to work on was the two forms of taboo: One at the level of general society (flourishing porn industry) and the other specific to movie-watching (voyeurism and cinema).

Peeping Tom was about porn and how it is a flourishing industry along with the “respectable” movie and newspaper industry. Powell’s serial killer exists between these two worlds showing how Times and Telegraph readers—and later cinephile Sight & Sound readers—could also be greedy porn enthusiasts, and how a creepy guy with a camera could easily pass himself off as an Observer photographer.

The central underlying theme of the film is voyeurism—or as a jolly psychiatrist describes it later in the film, ‘scoptophilia — the morbid gaze’—captured through the “aggressive and violating camera,” as Martin Scorsese puts it. Like Mark in the movie, Powell wanted to make the “perfect film” about films which does not take any obvious moral stand, but deploys all kinds of devices that make for commercial audience appeal.

Right from the extreme close up of the eye opening in the beginning of the film to Mark filming his victims’s murder in order to make a “documentary” and rushes from the commercial movie studio along with mixture of scientific footage and home movies taken by his psychologist father, who used Mark as a guinea pig in studies of fear speaks of a sense of “films within a film”. Home movie videos have been used with a very morbid twist here. The home footage not only provides us with insight into the life and experiences of young Mark, but they also become the genesis of his life-long voyeurism. Through the act of watching the home movies, Mark relives his victimisation.

Perversely, these movies chronicle the break-up of a family rather than the usual solidarity, and thus stimulate rather different emotions. At the end of the home movies, we witness the symbolic gift, the camera, given from father to son, a compensation for the lost mother and alienated affections. It is at this point that Mark crosses over from victim to future victimiser, from object to subject, from actor to filmmaker, the maker of his own home movies. As viewers of the film we experience a similar process and thus come closer to understanding Mark’s dilemma—this is one of the ways Powell implicates us.

And that’s not all. In the final two minutes, Mark kills himself amidst a popping of preset flashbulbs and the babbling of multiple tapes, as if developing from his brain as a stream of his repressed childhood memories; the police break in; the film runs out in Mark’s projector; the screen fades to blackness with a ghostly exchange of words between Mark and his father. No closure is provided to the spectator. Powell takes this voyeuristic notion significantly further in by implicating both himself and the spectators. For example, at the beginning of the film, when Mark murders a prostitute, we are implicated as voyeurs. Powell lets us see exactly what Mark is visualising through the lens of his camera as he prepares to film her gruesome death. He focuses on the camera as a crucial prop in the representation of voyeurism. Mark demonstrates this voyeurism through his involvement with the camera and with the filmmaking process. Mark asks Helen towards the end of the film: “Do you know what the most frightening thing in the world is?” What is perhaps more frightening is that we cannot tear our eyes away from the screen.