What defines a Bollywood film? In the song Dhoondo Dhoondo Re Saajna from Ganga Jamuna, Vyjayanthimala’s coy appeal for Dilip Kumar’s help in finding a lost earring epitomised the restrained, socially-permissible sexuality of the times. Yash Chopra’s Waqt introduced the template for multi-generational epic sagas that we’ve seen repeated over the decades in its various iterations, from Amar Akbar Anthony to Hum Aapke Hain Kaun. Deewar was a textbook model of emotional drama, its dialogue instructing us in what is truly important in life. Gabbar Singh, Shakal, and Mogambo raised the bar for bad guys, while Amrish Puri’s freakishly quivering red-veined eyes in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge injected the fear of God—and of Bauji—deep into the throbbing ventricles of our hearts. Pardes taught a generation of Indian girls to be good, and a generation of Indian boys to be protective of said good girls’ honour. Taal—by way of breathtaking long shots of the Chamba valley and serene close-ups of Aishwarya Rai’s pageant-winning face—showed us what a film really ought to look like.

Bollywood, especially pre-multiplex Bollywood, blusters with emotion and drama. It is lush, even gaudy. But we laugh through the slapstick humour and cry through the forced separation of lovers because the stories that undergird this massive cultural industry fuel our base impulses and make us complicit in all that ensues on screen.

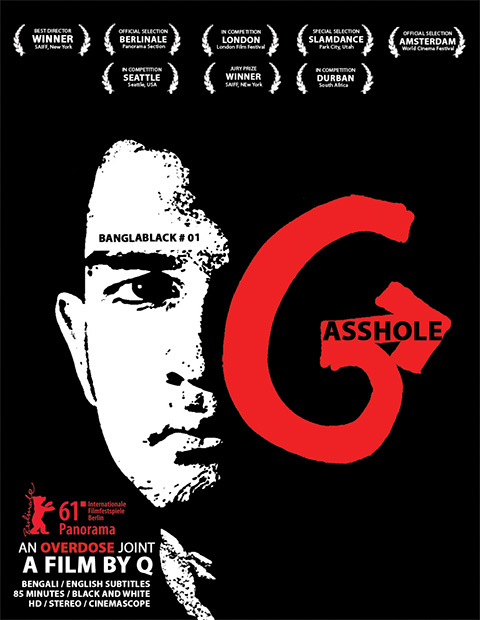

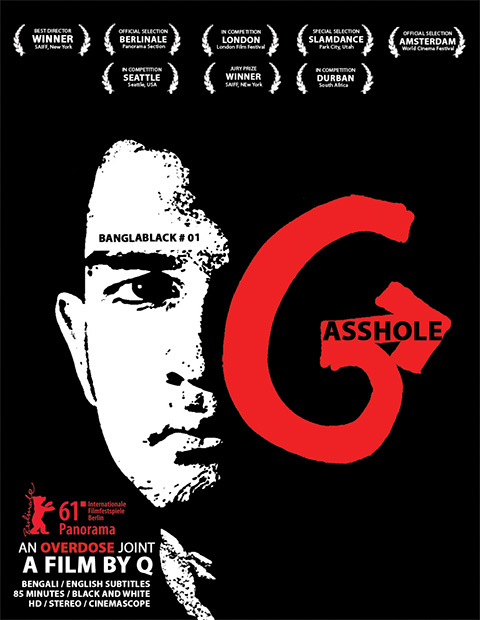

Qaushiq Mukherjee’s Gandu.

If this is an acceptable understanding of Bollywood cinema, the 2010 film Gandu, directed by Qaushiq Mukherjee—better known as Q—is the very definition of the anti-Bollywood. Shot in black-and-white save for a few scenes, every sparsely composed frame of this film serves as something of a negative image to the super-saturated and thickly populated visuals typical of Bollywood. Gandu walks right past the seamless narrative continuity that draws us into the world of most films, and blows the veneer of gentle and romantic marital sexuality to irretrievable bits. Does the film have anything at all in common with a standard Bollywood narrative? Yes. As Q himself describes it, the film is a musical. But even there, Gandu inverts the genre, presenting us with something we wouldn’t know to expect because we’ve never seen it before: it’s a Bengali rap musical, with a brutal soundtrack composed by the alternative rock band Five Little Indians.

Ostensibly, the film is about a disaffected young man who goes by the name of Gandu, whose only ambition in life is to make it as a rap artist. There is a cast of supporting characters around him, and each of these people help or hinder him along his path to success. But there is no epic journey here; Gandu isn’t your wronged-but-noble hero who has set forth on the thorny path to success. Living up to his name in all earnest, Gandu is an unequivocal asshole. An anti-hero at best, he is a creepy and slightly disturbed boy whose epic journeys are limited to sneaking into his mother’s room at inappropriate moments, wandering the streets of the city, and tripping on all kinds of psychedelic drugs with his only friend. His quest won’t bring tears to your eyes or that warm feeling in your heart. But you will also not be able to take your eyes off it.

The film jumps into the reality of Gandu’s life in the very first sequence: he lives in a large but inexplicably unfurnished apartment with his mother and her lover, the wordless and perennially sunglassed Dasbabu. Dasbabu and Gandu’s mother have copious amounts of sex, and Gandu uses these occasions to crawl into his mother’s room—while she and her lover are hard at it—and steal money from Dasbabu’s wallet. The money goes mostly into lottery tickets that never yield any return, and while this doesn’t deter Gandu from continuing to invest in them, it adds to his frustration with life. Aside from this, we get little in terms of establishing the setting: one scene in which Gandu is bullied by a couple of other boys is the director’s only allusion to the fact that he is ostracised by his peers. But the scene isn’t presented in a manner that evokes sympathy or provides an eye-opening understanding of why Gandu is the way he is. In keeping with the tone of the rest of the film, the scene is spliced between two unconnected moments and presented entirely without comment.

The turning point—if one may use that term for a narrative that consciously defies the trappings of conventional storytelling—is when Gandu meets Riksha, a cycle rickshaw driver who worships at the altar of Bruce Lee and accepts Gandu’s oddities without question. It seems natural that these two characters, both of whom teeter at the roughest of society’s edges, are drawn into a companionship. Gandu starts to spend all his days—and some nights—with Riksha. And after his mother discovers him in her room while she is having sex with Dasbabu, the two boys run away together.

There is a lot that happens in the story from this point forward, but that is almost of secondary importance. What makes the film spectacular is the form, and the effect the director’s stylistic choices have on the viewer. Right from the symmetry and stark contrast of the very first shot, where Gandu is sitting at a table against a window, Q’s framing and composition are striking. The film isn’t beautiful in the manner of any of the classics, of course—I’m not talking about Mizoguchi’s precise mise-en-scène or Tarkovsky’s surreal landscape shots here. I’m not even referring to classic composition as we understand it in Hollywood or Bollywood cinema, where a good shot is defined by how soft Katharine Hepburn’s hair looks, or how well-lit Madhuri Dixit’s face is when she raises a single sensual eyebrow at the camera. Q embraces aspects of filmmaking that are quite entirely impermissible in the world of conventional cinema, but because he does so with method and order, he manages to conjure a stark, almost abrasive visual beauty. I lost count of the number of shots in Gandu that were consciously back-lit, shots where a character’s face was in extreme close-up and yet I could only see him or her in silhouette. Q may not allow us to see the features on Gandu’s face but his silhouette, a solid black in contrast to the daylight around him, is framed with an understanding of aesthetics and visual balance.

The scenes where Riksha and Gandu are lying next to one another are hardly lit at all, and while the tightness of the framing includes us in their intimacy, the lighting only allows us to come so close. When Gandu is masturbating to porn, the unapologetic explicitness of the scene makes us want to look away, but its situation at that particular point in the narrative makes us want to root for him as well. Q’s greatest achievement lies in moments like these: he gives us pleasure while simultaneously denying it, he allows us to have no sympathy for his character while still getting us to back him, and he shows us the beauty of the mundane while sparing us none of the ugliness of life. In repeatedly pulling us out of the narrative and making us conscious of our position as the audience, Gandu’s disaffection pervades the viewing experience as well. In watching the film we turn into an anti-Bollywood audience: we are not carried away by the fantasy, and we don’t embroil ourselves in the drama. We don’t really care what happens to Gandu, but we cannot stop watching his life unfold.

Ironically (minor spoiler alert), the film does have a happy ending. But the journey up to that point takes us so far away from anything we may have expected that this token tip of the hat to classical cinema can do little to bring us back. I recommend Gandu both as a film scholar and a film lover. There is no dearth of films that attempt an anti-Bollywood, anti-Hollywood, or anti-classical cinema stance. But few among them actually get it right. Q himself has had missteps: his most recent feature Tasher Desh (2012), while representative of the aesthetic choices typical of his oeuvre, fails to come together. Even Gandu has moments when he gives in to his impulse for the gimmicky, as directors with a rigid vision are sometimes wont to do: the insertion of sections where he interviews people about the things that are happening on screen at that moment is, in my opinion, an unnecessary disruption. But my unfavourable opinion of these segments notwithstanding, they fit with the film’s overall pattern. Gandu succeeds in becoming the very definition of the anti-Bollywood. And as its anti-audience, I thoroughly enjoyed watching its disaffected anti-hero go through the motions of his life.