These days, most ‘bad’ films tend to be so popular that the Internet and other media are full to the brim with criticism for them—so much so that one can even find videos collected by film enthusiasts and critics for, um, illustrative purposes.

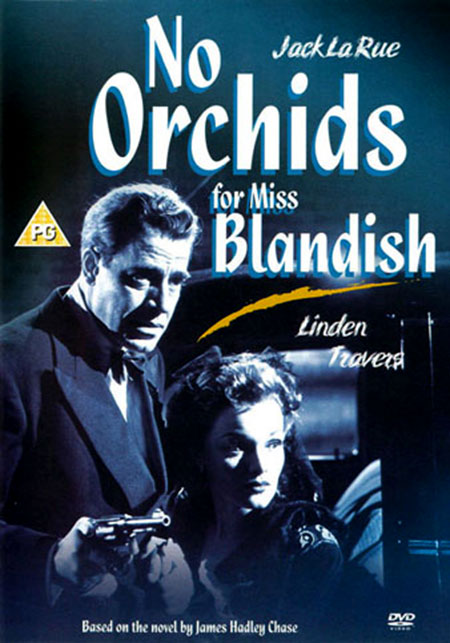

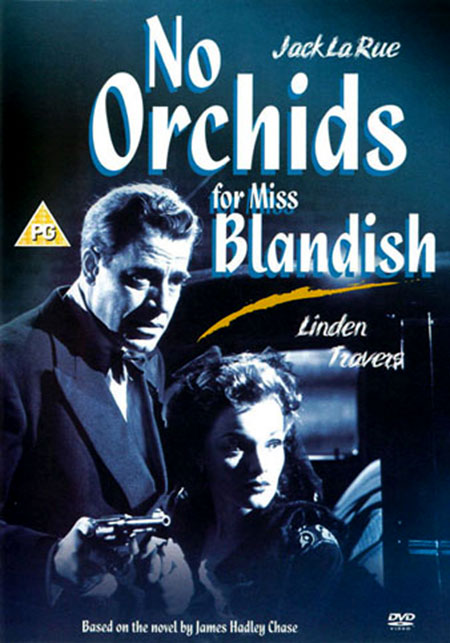

Even a film called Plan 9 from Outer Space is available to watch on YouTube, accompanied by the viewers’s comments—some who criticise the film for obvious reasons, and others who argue amongst themselves about another film that could officially have been the Worst Film Ever. However, No Orchids for Miss Blandish is different. Adapted from a James Hadley Chase novel, the film hardly has any presence on the Internet. This isn’t the kind of ‘bad film’ that has become everyone’s punching bag over time. In fact, far more humiliatingly, it has just been ignored.

No Orchids for Miss Blandish film poster.

Reading the book on which a film is based, does, to some extent create a bias in one’s mind about the quality of the film. And it did happen to me as well. However, in a way, that made me a bit more liberal about the film as a whole. Even with the original book, after the first 50 pages, I was inclined to believe that the book might have the Stockholm Syndrome as one of its themes. As I read further, I was disappointed—not only were the advances between the captor and the captive one-sided, the end of the plot (even for a dispassionate reader like me) was a little too gloomy as well. But I will admit that despite its violence, I did enjoy the book. If I hadn’t read the book, I would have been more critical of the film, but usually in adaptations, some creativity often serves to make the plot better. The film follows the book for most part, except probably in the development of the characters. But then, writers usually aren’t bound by limits, unlike filmmakers, who have a two to three hour window to present their plot.

One of the film’s major failings has been in its refusal (or perhaps inability) to change the setting from America to England. British actors speaking in an American accent creates dissonance, and makes them look like wannabe theatre artists trying hard to get into character. Why, we wonder, weren’t American actors used? Why wasn’t the setting changed to England? A cheap book doesn’t necessarily have to translate to a cheap film, does it?

Another shortcoming of the film has been the gratuitous violence, which is where the film most closely resembles the book. The book, too, had been castigated for the brutal subplots that many felt were unnecessary. But violence itself doesn’t make for a ‘disgusting’ film. And that’s exactly what critics at that time panned the film for: being disgusting. One has to bear in mind that the film was released in 1950—much before filmmakers had discovered an acceptable and even entertaining way of displaying violence. Had St. John Leigh Clowes, the director, seen films such as Reservoir Dogs, or even the Korean film Old Boy, he would have thought of a better scene setting. Now, films like Taken have been declared as low-budget hits—their U.S.P. being ‘action’: countless corpses scattered while someone seeks revenge. If No Orchids for Miss Blandish was re-released, or better (or worse) still, remade in this era, would the audience be more accepting of its bloodshed and bullet showering? I wonder.

If I had to pick one thing about the movie that really didn’t work for me, it would be the lack of exploration, or evolution, of the relationship between the captor and the captive. The half-crazy Slim’s feelings for Miss Blandish aren’t just the obsession of a sex-starved, subdued man. His feelings are an attempt to find the hidden humanity in himself. In the book, at times, one gets to see the weaker side of him—his dependence on his mother, his inadequacy to resolve issues without bloodshed. Slim’s character is an amalgamation of strengths and weaknesses that evoke a perverted form of sympathy—the kind of sympathy that one could feel for The Tempest’s antagonist, Caliban. He is the exact opposite of Miss Blandish; she is suave, soft-spoken, and neat; he is unruly, violent, and maniac. Yes, opposites do attract, but for it to happen as easily as it does in the film? That seems unconvincing. After all, Miss Blandish has been placed with a dangerous man, and one would expect more than just rowdy behaviour to make her forget her fiancé’s death, and fall in love with Slim. The love-by-fear idea is not reliable and adds another shortcoming to the long list of mistakes.

Amidst all the criticism and allegations of the unwarranted body count, it is really surprising that the film remains an obscure entity. Interestingly, Linden Travers, who played Miss Blandish in the film, called this role her favourite. Alas, no one even seems to have noticed.