A Clockwork Orange, directed by Stanley Kubrick, becomes a film which embodies the conflict between individual free will and state control. On the surface, it is a straightforward film about a juvenile delinquent—Alex—who is the leader of a gang consisting of four almost mystical men, who he calls his “drooges”.

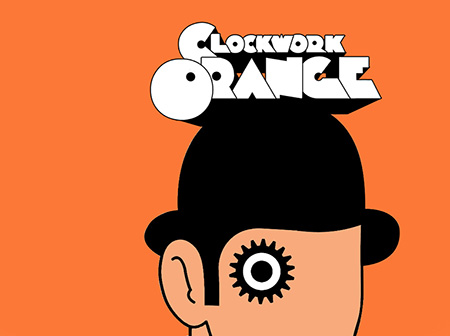

Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange.

After murdering a woman, he is convicted and placed into jail, following which he volunteers for “conditioning” to get out of the prison. In the process, he is conditioned to become sick at the very prospect of sexual or aggressive action, and is then released to be abused by all his former victims. Hospitalised after a suicide attempt, he is “de-conditioned” by a government now fearful that he may prove to be an embarrassing example of its social engineering, and at the close of the film Alex, and his subversive character is fully restored as he smiles wolfishly in the embrace of the slimy Home Secretary.

The equation is clear and neat: The brutality of the first differs little from the brutality of “law and order”. Except that this isn’t, in fact, Kubrick’s point. Quite clearly, he prefers the brutality of the first, for Alex is made charming while the Home Secretary is thoroughly deplorable. The means by which Alex is celebrated are simple enough: He is not made into a morally significant figure, but into a comic hero. A Clockwork Orange is one of the most technically stylised and cogent films made by Kubrick, which in the same moment is metaphorical, witty, bizarre, thrilling, frightening, musical, political, comical and sardonic.

The 1970s (especially in Britain) was considered by many to be a decade of violence. It was considered as a liberal and truly disturbing time. It saw the rise of Teddy Boys, Mods, bikers, skinheads, punks, school students, teen girls, and Rastas—people who deviated from the norms of the dominating culture and emphasised on the non-compliance with authority by forming their own subversive collective identity, in the fear of not getting isolated.

This was also an open period of film censorship in Britain. Therefore, when A Clockwork Orange came out it was marked as a film that spoke for the people who were the apostles of violence and a time when the social horizons were literally very dark indeed. Many critics and policy- makers felt that youngsters were doing what they were doing because of what they saw in the film. Some local councils banned it by terming it as “REAL pornography”. It cannot be disregarded that the film has a mimetic quality that certain people who watch Alex and his drooges are almost tempted to ape—if not the behaviour, then at least the poses, which can be frightening enough. However, to dispel the film as being a technique of brainwashing is being over-deterministic.

‘This is the mirror and I hold it up to you.’

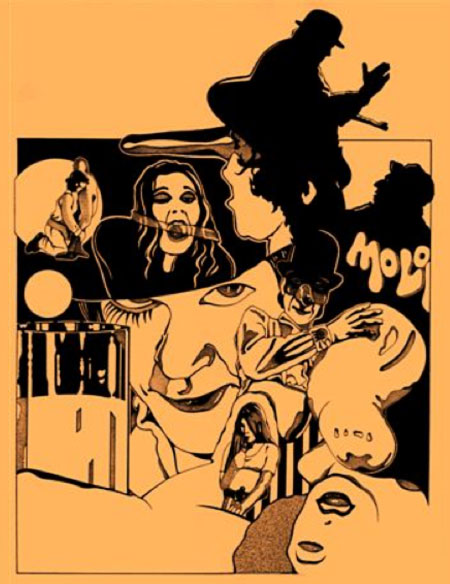

In an Interview, both Kubrick and his star Malcolm McDowell have referred to the picture as “satire… social satire dealing with the question of whether behavioural psychology and psychological conditioning are dangerous new weapons for a totalitarian government to impose vast controls on its citizens and turn them into little more than robots.” The dystopia, violence, and subversion are illuminated at many levels in the structuring of the film—the language, music, and mise en scène. The language used in the film— Nadsat—seems to be a confused mix of Russian Slavic and gibberish words. The language speaks of a sense of alienation that may be felt by the protagonist and the other teen speakers, since it cannot be understood by mainstream society (which includes the spectators).

The music thrashes out at the audience with the following assertion: ‘You think you are very civilised? That art has become so advanced that you are incapable of relapsing back into the animal world? Think again. This is the mirror and I hold it up to you.’ Most of the ‘ultra-violent’ scenes involving rape, murder, violence, and sexually violent fantasies are performed with a classical music score in the background, and Beethoven’s music provides a continuous narrative of action, which rises with the acceleration of drama—especially in the final sequence of the film where the film, music and Alex all reach an ecstatic climax of liberation.

Kubrick has suggested that the violence portrayed is somehow “sterilised” by the mythic stylisation that he has given to it. Violence is theatrical. The fact that it is set to music keeps you at a distance from it. You are not invited into it, to gloat. It is the abstract effect of violence that makes an impact. The contrapuntal use of music makes up delightful scenes in the film, emphasised in the slow motion sequence of Alex attacking his gang and the high-speed sexual escapade with two teenage girls. Even in the most talked about scene in the film, where Alex and his gang enter the house of the journalist to assault him and his wife, Alex kicks them around reciting the celebrated musical love number by Gene Kelly, ‘Singin’ in the Rain’. What becomes disturbing to the audience is the misappropriation, but it is this misappropriation that has made it memorable. This absurd scene lodges somewhere between your heart and head which creates the disturbing friction, and it is from this friction that you feel the presence of Stanley Kubrick and his style.

Voyeurism in A Clockwork Orange is inflicted by two things—one, audiences may feel implicated because of the low angle static shots which capture a theatrical event, making the audience contemplate because the apparatus doesn’t lead you to look at something specific. You make your own way through the film as your mind wonders. This, along with the jeering voice of the narrator/actor Malcolm McDowell, really gets under the consciousness of people—both parts of the cinematic illusionism, which a film like A Clockwork Orange tries to break as well as hold on to.