Rohena Gera’s Is Love Enough? Sir opens with Ratna (Tillotama Shome) in her village home packing her bags to leave for the city to which she has been unexpectedly called back. We see her making her way to Mumbai, navigating the long road back on scooters, buses and trains, with the greener, airier, open roads of the village being slowly replaced by views of skyscrapers, the sea, crowds, grime and traffic outside her window as she approaches the city. Her wearying trip ends at the swanky apartment of her employer Ashwin (Vivek Gomber) which she must ready for his return. From one home to another, Ratna’s journey in this roughly three-minute sequence establishes right at the outset the contrast between the two worlds that will exist in parallell in this film, while also tracing both literally and symbolically the route its heroine has traversed in search of work, independence and selfhood.

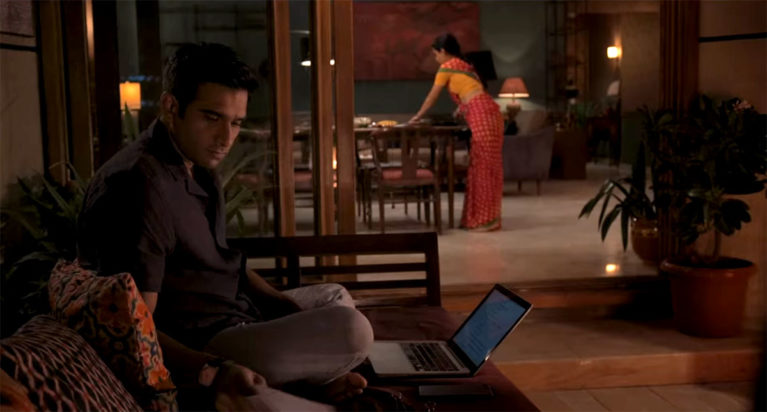

Ashwin’s plush Mumbai flat, where Ratna is engaged as a live-in maid, houses these two disparate worlds. The two characters typically occupy separate spaces within the home, and the camera pans across these spaces—a visual movement repeated more than once in the film—to track their simultaneous activities, highlighting, in spite of their proximity, the distance between their places in society. We see him in the living room reading and working and her in the kitchen preparing his food, him in his spacious bedroom watching television and her in a cramped back room doing the same. The camera also frames them together as they interact, with the frames themselves progressively bringing them physically closer to underscore the growing bond between them. Wider frames with Ratna and Ashwin positioned apart, often with furniture separating them gradually give way to tighter frames situating them together inside elevators and in hallways. The home, closed off from prying, judgemental eyes, is also, if momentarily, an empathetic space, allowing conversations and the forging of a connection that could not have developed or existed outside of it; a fact that Ratna, who declines Ashwin’s invitation to step outside together, is only too aware of.

The home, closed off from prying, judgemental eyes, is also, if momentarily, an empathetic space, allowing conversations and the forging of a connection that could not have developed or existed outside of it; a fact that Ratna, who declines Ashwin’s invitation to step outside together, is only too aware of.

The film’s central characters, like the spaces and worlds they inhabit, are dissimilar, each serving as a foil for the other. A common enough trope in romances, the idea is only gradually discernible here because of the one point of difference between them that overshadows all others; that of a deeply entrenched social variance. Driven, earnest, and hardworking Ratna moved to the city to work so that she could be self-sufficient after her husband died within months of their marriage. She hopes her younger sister will have a better life because of the education she is helping her acquire and herself dreams of and trains for a career in fashion design. In contrast, Ashwin is lost and forlorn, having recently called off a wedding he realised only belatedly he could not go through with. He helps out at his father’s construction site but it is his old writer’s life in America that he pines for and seems better suited to. The perceptive Ratna senses this longing in him, ultimately inspiring, unwittingly, his move back.

So much of Shome’s stellar performance in this film, given its long and frequent silences, resides in her body which imbibes a language born out of Ratna’s efficiency and optimism on the one hand and the daily insults and humiliations she faces coupled with an ingrained sense of her social place on the other. With her gentle nods to the perfunctory ‘thank you’ s she receives through the day and a face that lets out what her words are often not permitted to in the presence of the people she works for, Ratna walks a delicate line between an initial physical awkwardness around a male employer and a swift and ready resourcefulness; between a measured restraint with regard to the personal lives of those she serves and a sincere willingness to reach out to them. Vivek Gomber’s Ashwin with his quiet, brooding writerly sensitivity and as the only member of his class who sees and respects Ratna for who she is, is very likeable while Geetanjali Kulkarni as Laxmi, another live-in maid in a neighbouring flat and Ratna’s maternal companion, infuses her brief scenes with such compassion, candour, and humour that it leaves us wishing she was more central to the story.

Formerly simply titled Sir when it started screening at festivals in 2018, the film’s later addition of ‘Is Love Enough?’ is interesting because of the way it draws attention to an early admission Ashwin makes regarding his recently terminated relationship. For Ashwin, “it wasn’t enough”, as even though the girl in question was a perfect fit in every way, implying that she was acceptable to the family having even supported them at a time of crisis, there was no love between them. The film’s new title which alludes to his relationship with Ratna sets it up as the inverse of his previous one, as if rearranging their determinants to challenge him to make his choice. While Ashwin’s solution to the question posed by the title is unsurprisingly fanciful, the impossibility of the idea it suggests is made amply clear by the reactions of the people around him to it.

Ratna’s uprightness, practicality and sense of pride make her seek a different route. She agrees to drop the ‘Sir’, a term she has used to address him throughout, a term that has defined their relationship thus far, forcing them into roles they now wish to escape. Leaving his employ frees her from that bind if not from society’s prejudices. Calling him by his name then marks a departure from old identities and dynamics in favour of new ones. Standing at the threshold of a new life and possibilities, this, for the moment, is perhaps enough for Ratna. Love, though, is another matter.