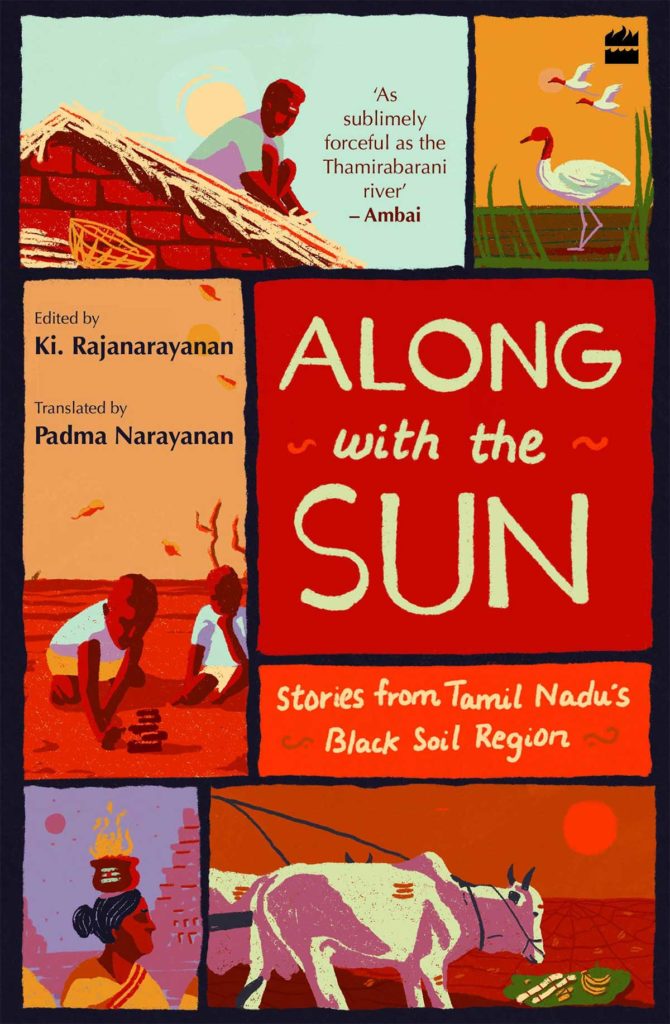

Along With the Sun: Stories from Tamil Nadu’s Black Soil Region is an anthology of 20 stories originally published in the 1980s. The brainchild of Ki. Rajanarayanan or ‘Ki. Ra’ to the writers’ collective that blooms under his shade, the anthology is composed of twenty such Tamil writers he coaxed and nurtured into literary figures over the years. The stories are written in a realist mode chronicling vignettes from the lives of people in the Karisal region of Tamil Nadu— the eponymous ‘land of the black soil’, where rain is scarce, the sun unforgiving, and the parched unpredictability of the fields translates into a ceaseless preoccupation with water.

Written as they are about the people of a particular region, the stories cohere into a collective voice that presumably marks what contributing writer Cho. Dharman calls ‘Karisal literature’. The stories have several stylistic similarities, such as an elliptical nature of introducing characters via their relationships to one another; characters who are quick to sorrow or lash out, and dramatic about how they do it; adhering to the virtues of writing how people speak; endings that arrive almost uniformly before you expect them to and are usually bitter— or more appropriately, laced with salt. In his introduction, editor Ki. Ra relates the lack of water in the region to the aridity and harshness in people’s natures.

Water, the search and wait for its arrival, is a tangible presence throughout the anthology. People are quarrelsome and gush forth with the emotion in an abundance their streams do not have. The sky without rain is “a deep hole without a drop of water”.

Water, the search and wait for its arrival, is a tangible presence throughout the anthology.

The good: Working-class struggles are rendered with clarity and immediacy. The language is beautiful, leaning towards evocative description. In ‘Dry Leaves’, the skilled writer has you empathising with the material plight of wife-beater Sankan, who cannot control the urine soaking through his veshti. Here is water, in reverse— a deluge from the sky in a scene reminiscent of the tortured fugue state Elena Ferrante’s protagonist experiences in Days of Abandonment. In the story ‘Arrival’, a man is woken from his sleep by a voice that “pierces him like a mosquito bite” and the sweat from his skin “maps a picture on the ground”.

The poetry in some of these lines is startling— even in translation, perhaps especially in translation. For instance, when people go to relieve themselves, the stench is described as “rising as high as a palm tree throughout the village”. Translator Padma Narayanan does a wonderful job with lines like “Just as one picks out particles stuck between the teeth with one’s tongue, they scraped out the grass stuck to the edges of the fields with small sickles and gathered enough…”, which will leave a trace in your memory long after you’ve turned the page.

A sliver of a story by Gowrishankar about baby white cranes (Krauncha birds) caught in my throat like a shard of glass. ‘Dearer than Life’ is another standout, where a man given to fainting spells would rather risk death than stop working on thatching roofs, a task which lets him perch high from where he can view the dominant castes of the village as ants crawling beneath him.

However, after a while, the overly descriptive language can get to you. One of the stories, ‘Ruin’, takes on magical realism in its florid passages that read like a delirious ‘Overstory’. Sample this: “Unlike other women, Paneerakka was sensitive to the sorrow of the wandering birds— for was she not a wood nymph?” I gagged. Then I read that this intolerable Paneerakka had mynahs combing her hair.

The book begins with stories that are unremittingly bleak— the first two end, literally, in tears. Eventually, it settles with spaces where you can put down the sense of anticipatory dread that the stories have cultivated in you thus far. But not for long. For the most part it traffics in uneasy endings.

As a work of translated fiction, does it entirely succeed? To my mind this depends on three things: whom the editors imagine their audience to be, what we expect of work being legibilised for an audience likely to include people unfamiliar with the language or region, and what the editors and translator of the anthology wanted from the work.

The stories here are significant to Tamil literature and have been the subject of school syllabi and research for years. With this translation, they are available in English for the first time.

Recently on Twitter, the writer Moni Mohsin said of Megha Majumdar’s acclaimed novel A Burning, that she was “struck by how often local Indian food the characters eat is explained in English. Kachuri with chholar daal is explained in the next stand alone sentence as ‘fried dough stuffed with green peas, and a lentil curry’”. This, in Mohsin’s opinion, detracts from the experience of reading. She further points out that we don’t expect these gymnastics from Western writers who feel free to sprinkle ‘eiderdown, pretzel’ and so on into their work. I tell you this to say that this thread played on my mind as I read the anthology woven throughout with Tamil words like aatha (and interchangeable aathadi), modalali, Moodevi, and so on. There is a glossary, but Tamil words and phrases for various cultural rites, and titles of kinship, particularly the interchangeable ones, are so frequent that the lazy, indisciplined reader in me felt frustrated by the interruptions as a non-Tamil speaker.

The stories here are significant to Tamil literature and have been the subject of school syllabi and research for years. With this translation, they are available in English for the first time. In her translator’s note, Padma Narayan writes that if the stories are able to bring about an awareness of the evils of caste, she would feel the work has achieved its purpose. By that metric, she can sleep soundly.

Here’s what I will say. After reading the collection, I came away tormented by the reminders of the countless stupid ways Indians have devised to be cruel to the ‘others’ that they have arbitrarily designated as ‘lower’ based on outdated scriptures kept alive into the 1980s, when these stories were written, and 2021, where we read them now. It’s not a particularly uplifting thought but these are not particularly uplifting realities. You could argue that dominant caste-society in India needs this reminder.

Caste and its machinations are the roiling life-blood of this collection, that rises to centre-stage occasionally. In ‘A Way of Life’, you see it in food, and a passing reference to a college shut down over a protest. In ‘Women with Flowers on their Thalis’, a Dalit woman is compelled to to walk barefoot along a circuitous route for water, and in the denouement take on the tasks of the entire village in a 1980s Dravidian version of ‘Dogville’. Sparkling observations bring it to life in dialogue such as the sad, neglected wife in ‘Sharing’, who lingers over her hot-water bath because not having ‘ghee or wealth’, she can only lust after water. In ‘The Solitary Householder’, a minute lack of custom compels a departure. It takes centre-stage, sprouting separate water-wells and sets houses ablaze in ‘Helpless’— one of the most striking stories of the collection.

Then again, you could argue as Black scholar Namwali Serpell does, compellingly, that the idea that art promotes empathy is ultimately a platitude. On my part, I am mostly unconvinced that reading about the horrors we casually inflict or are complicit in, elicits a change in behaviour. But again, we have arrived upon the question of intended audience— who is it for instance, that does not know the evils of caste?

Perhaps ‘enjoyment’ is not the point in stories about the everyday suffering of a people whose very lives are marked by suffering.

I don’t think I am the intended reader for this collection, and I can’t say that I enjoyed it. But perhaps ‘enjoyment’ is not the point in stories about the everyday suffering of a people whose very lives are marked by suffering— which is another way for me to confess that even within suffering, I am biased towards finding brief utopias or moments of happiness. (The pursuit of the bird in Fandry, sinister as the plan behind it is, the dreaming, is as important as the stone flung at my face when it comes.) And the moments of happiness when they surface in this collection are few and are quickly snatched away.

Still, literature of drought, rain, and agriculture is especially resonant with this moment where the farmers’ protest is at the forefront of our minds. If you go by what farmers have to say for themselves, and the mass exodus from agriculture in the past few years, it’s a bad life. From 1980s Karisal to 2021’s Punjab, stories of scarcity should not be timeless, but they are. Perhaps the ground is fertile, after all, for the receptivity of readers to this collection of stories set in rural India.