“Sometimes when a piece of art draws cries of ‘this is random, anybody could do this’, its goes back to one of the earliest arguments, as soon as people started to make a break from any sort of representational art, anywhere. In cases like this you cannot argue about quality of technique, you have to acknowledge that this has a theoretical presence and an intellectual basis for it; it has nothing to do with a measurable technique. It has to be recognised that art is being done here which is not representative, and it’s not supposed to beautiful or attuned to any sort of standard in commercial sense.” — Byron Coley.

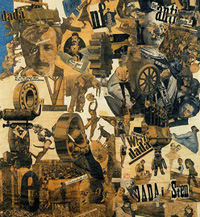

Dadaism

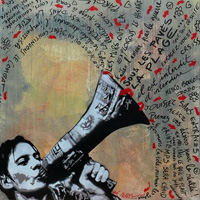

Situationism

Fluxus

Abstract Expressionism

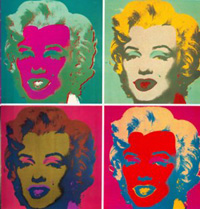

Pop Art

Conceptual Art

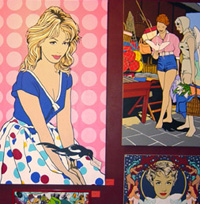

Stuckism

Surrealism

What exactly is worthy of being called art? What distinguishes an ostensible piece of art from an everyday artefact? What is it that allows us to construe an idea with artistic merit as opposed to an outlook of triviality? The fact that there has never been, and probably never will be a strict definition of the word should be proof enough that the word holds innumerable dimensions. While some see it is an expression of human endeavours in its most primitive form, others believe it to be the true idiom of a rich and multi-layered emotional being. With such an extensive and subjective description of this universal word, most modern day art connoisseurs don’t dare fathom the convolution of the term that is ‘Anti-Art’. But it is in the context of this idiom that art may truly be appreciated in all its variable forms.

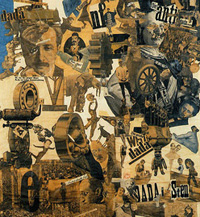

Simply put, anti-art is a long lineage of counter-movement ideas designed to kick out against the complacency that the art world has a tendency to settle into. Originating with the Dadaists in Europe following World War I, it represented a new generation of artists who shared a nihilistic outlook toward the standard expectations of arts and literature. Removing themselves completely from intellectual analysis, they employed anarchist ideas generally unheard of at the time, to undermine the ruling establishment by employing outrageous tactics in the vein of demonstrations, manifestos, and heavily absurdist art critiquing social values and providing an alternative to the constraints of 1920s art.

Photo montages and collages made of trash and refuse material were premeditated to scandalise the general public opinion while perhaps the most famous and controversial Dada artwork, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, consisting of only of a urinal set on its back raised a powerful question on the validity of art. It also attacked the ideal that art takes time and effort to create, establishing the concept of ‘readymade or found art’, something the pop art movement would borrow heavily from.

This granted artists such as Duchamp, along with Kurt Schwitters and Raoul Hausmann, who were recognised as famous Dadaists, a place in art history as conveyors of the first anti-art movement influencing surrealism, punk rock and avant-garde music akin to the experimental band Sleepytime Gorilla Museum named after a small group of Dadaists.

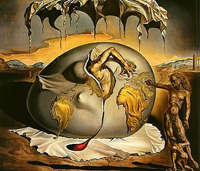

By 1920, the blatant politicisation of art began with the rise of communism in the Soviet Union and along with an expressive break from Dadaism in the form of Surrealism and later Abstract Expressionism. Although by no means as outrageous as the radical Dada artists, the leftist ideas soon manifested themselves in emotively conceptual works of famed artists Salvador Dali and Jackson Pollock respectively.

Arguably the most politically-charged movement in the ’50s came in the form of the Marxist-inspired Situationism based around the ideas of an international group of artists — the Situationist International. Melding art and politics into a single concoction for the purpose of overcoming the forced suppressions of a capitalist rule, and eliminating Dadaist and Surrealist ideas while calling for a cultural revolution, was the basic concept. Although largely overlooked, the Situationists were solely responsible for trouncing the notion that art exists as a separate entity, and integrating it into the fabric of daily life, influencing not only music but also the application of graffiti and street art in reclusive underground artists like Banksy.

Fluxus, a global movement which embodied the true essence of the avant-garde took form in the ’60s, retaining the anti-art and anti-commercial spirit of Dadaism, however with a stronger objective for experimentation, creating a socially aware population and the belief of living the art. Centered on ‘scores’, essentially a collection of works designed by an artist with prominent instructions on how to recreate and reinterpret the piece by others, thus propagating the do-it-yourself ethic, the concept breathed new life into age old concepts of sound art, visual poetry, and an amalgamation of different artistic media. Unplanned mass gatherings of people to witness improvised performance art at unusual locations termed ‘happenings’ was considered a characteristic feature of the movement, personified in the notoriously controversial performances of Carolee Schneemann. With a notable alumni consisting of Dick Higgins, John Cale, and Yoko Ono, the core values of the movement would prove essential to New York’s No Wave scene.

Gaining prominence around the same time, the last movement of the modern art era was a reaction against the prevalent pretentious workings of Abstract Expressionism. Born out of the enthused Neo Dada crowds, Pop Art, acting as a bridge between high brow and low art, made heavy use of mass culture themes and techniques such as billboard advertisements, consumer product packaging, comic strips and celebrities. Andy Warhol’s renowned painting’s of banal and everyday topics such as Campbell’s Soup Cans, Coca Cola bottles, Marilyn Monroe, and Elvis, expressed a positive outlook on modern consumer culture while challenging the topical sensibilities of an accustomed art world.

The Postmodernist era continued to take its cues from the ubiquitous belief in reducing contemporary art to a derivative of intangible ideas, foregoing aesthetics in favour of concepts. Conceptual Art became the beloved stance of most artists during the ’90s, chiefly led by the collective Young British Artists, who offered up the notion that the deliberation of an idea was more imperative than the actual executed product. A dead tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde in a vitrine, or a disheveled bed stained with bodily secretions and detritus objects presented by prolific conceptualists Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin respectively, offered up a nonfigurative visual experience that polarised artists and audiences alike.

Refuting the notion that anything can be considered art, Billy Childish, along with Charles Thomson and his radical art group Stuckists, expressed an obstinate desire to lead away from the pretentiousness of conceptual art, as pop art had done against abstract expressionism decades ago, in this case however by means of manifestos and protests against postmodernist art which they believed to be a cold and mechanical view of culture. The ‘Anti-Anti-Art’ philosophy of Stuckism championed realism over the deliberate abstraction of conceptual and performance art with an ideology of Remodernism, returning art back to its creative passion and clarity in age old disciplines of figurative paintings.

In conclusion, while the recent back-and-forth spat between the conceptualists and the Stuckists, or the basic concept of anti-artists demonstrating against anti-artists may seem trivial, and a remote take on the perennial objective of the Dadaists, it is, however, in retrospect, a representation of the new millennium’s version of the imperative question: What exactly is worthy of being called art?

Looks like a wiki entry frankly. Not at all worth reading.

Brilliant piece of work…

Informative yet interesting…thought provoking indeed…

I believe that any piece of work that appeals to me is art..and in that case you are an amazing artist!!

Relevant article. Although the Dadaists are anti-art, they're clearly still defining art by defining it (a) in terms of what its not and (b) by loosening the parameters, albiet to a very great extent. And while the notion of “anything goes” is great in theory (and holds ground in fact- are we not being artistic on an everyday basis when we put together a particular outfit or combine food in particular ways?) the fact remains that notions of an elitist and exclusive art is still deeply embedded in our psyche. To quote from your own piece: “Fluxus, a global movement which embodied the true essence of the avant-garde ..” “True essence” of avant-garde? Really?

Well according to me everything is art. Since the artists consider their creations to be art and see it in that context, it should be proof enough for its validity in the art world. Everyone should be allowed to have their own perception of what is art and thus in the so called 'great debate' between stuckists and conceptual artists, I would have to go with Damien Hirst and co.as clear winners.

You raise possibly the most important question facing art at the moment, namely what we should call “art”, as opposed to some other classification. This doesn't just reflect on artistic values, but on wider values about what is important and meaningful in human existence. I might mention that Stuckist “realism” is not restricted to the material, but also encompasses the psychological and spiritual dimensions of experience.

Charles Thomson, Co-founder, The Stuckists

@Francis: I am glad everyone is allowed to have their own perception of what art is, as I can then have mine that not everything is art.

Charles Thomson, Co-founder, The Stuckists

Exactly, since you respect different people having different interpretations of art, how then can you justify stuckist protests, at say the Turner prize for instance?

I respect they can have a different interpretation, and I respect that I can have a different interpretation to their interpretation. I respect that one can have an interpretation that someone else's interpretation is a wrong interpretation. I respect the fact that they are entitled to have, in my interpretation, a wrong interpretation, and I respect my right to assert their interpretation is a wrong interpretation. I also respect their right to assert that my interpretation is wrong that their interpretation is wrong. Some people seem to find it very hard to accept all of that, and think that accepting someone's right to hold an interpretation means you shouldn't say they're wrong to hold it. It doesn't. Quite the opposite.