Man Bites Dog (1991) is a film shot in documentary format in grainy black and white, following the killing spree of the murderous serial killer Benoit. The film opens with our “hero” strangling a woman on a train, and then cuts to his lesson on how to properly dispose of the corpse—a film which begins with viewing violence for laughs turns into a disturbing and sour satire.

Its realism has a fictive tone (in terms of the theme), complete with choppy editing and unsteady hand-held camera shots, and is reminiscent of cinéma vérité and gives that authenticity to the film. Added to that, the three main characters in the film use their real names. The filmmakers are Remy (Rémy Belvaux), Andre (André Bonzel), and Benoit (Benoît Poelvoorde). Man Bites Dog may seem to be a laudable successor of A Clockwork Orange as this generation’s most telling and uncompromising look at our views on violence. But Man Bites Dog filters that through the lens of the media and its fascination with televised tragedy: the more real, the better.

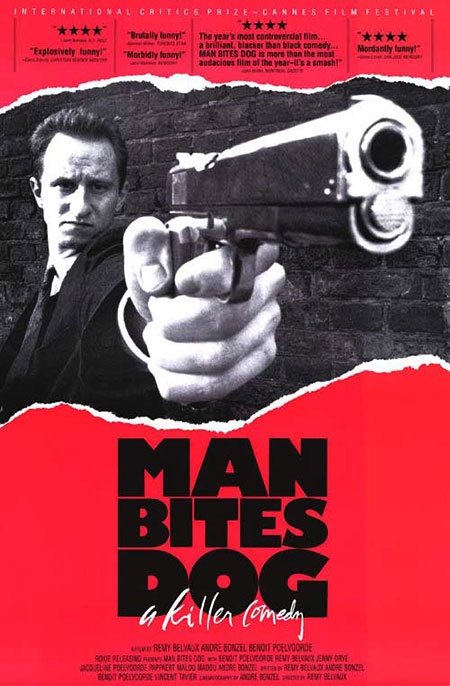

Man Bites Dog.

This film that won the International Critic’s Award at the Cannes Film Festival in 1992, while carving out a figure as entertaining as the killer (brilliantly performed by Benoit Poelvoorde) tries to comment on the documentaries and reality T.V. that survive on manipulating the sordidness and entertainment value of those who are captured on camera. Benoit doesn’t see himself as just a murderer. Most importantly, he’s a man who wants an audience, and he does have his own crass charisma. Benoit certainly thinks he deserves a movie, in which he’s a star, and the film crew agrees. In documentary films, the pleasures arise not through make-believe or fictional enactment, but by the presentation of actuality, of two contradictory desires. A reality on one hand, which involves the camera as a mastering, all-seeing view; an aid and supplement to vision and logical interpretation whereby we are shown a social reality that our own human perceptual apparatus cannot perceive. On the other hand, there is a desire for the real, not as knowledge, but as image, as spectacle—“The Spectacle of Actuality”.

The period of paranoia attached to cinema as a social machine should be considered long past us. Earlier, cine-psychoanalysts may have jumped to answer the above question by drawing comparisons between the movie-viewing process and the illusion of a solid-state ego given by the mirror phase, as hypothesised by Lacan. Such nascent origins can be touted as the reason for the fear and the instinctive lashing provided to cinema, blacklisting the apparatus as a propagator and appropriator of voyeur-centric behaviour. In fact even in Man Bites Dog, which can be categorised as capturing the voyeurism of the “real” due to its story and the way it is shot (providing moments of pseudo-realism), one can bench on the above attestation. As a precursor to the shady Brussels apartment scene where Benoit and the crewmembers take part in a gang rape of a woman in the couple’s home, one watches Benoit and the others intoxicated in a bar. When the woman bartender has had enough of them she shuns them away by saying-“I have had it with your grossness”. This is followed by Benoit exclaiming at her in a jubilant high, with others sniggering in the background: “Just say I disgust you! … All because I have some faults!” This cuts to them walking on the streets singing: “… Cinema! I’ll go because I am Cinema! … From screen to screen, film to film, gave you my life… And you, Gabin, son of Lucien, it made you a good boy again… All together now!”

I think this scene was intelligently charted out as a way of mocking at the myth about cinema. The singing is a jibe at the spectator—by jeering “I am Cinema”, the following grotesque scene and its validity can be promulgated to the fact that Cinema has always been the medium of such perversity. In that sense, Man Bites Dog becomes not only a satire on the fascination for televised tragedy, but also tries to joke about the uncalled stain provided to cinema.

It is critical to highlight that these three films drive home the point that this so-called voyeurism is actually found thriving on the opposite side of the screen—amongst the audiences who watch it. The spectator engages in peeping-hole phenomena and the idea of the scopic drive cannot be a natural category, it is constructed. The only way the films can be considered guilty is that they work on a cynical view of the spectator. The reason why these films have been so ahead of their time during the period in which they were made/released is that in some way or the other, they are self-conscious or self-reflexive, which has invited bashing from spectators, including the mainstream critics.

What these films do is “deprive the cinematic game of its illusion”. The mechanism that they use to intrude upon this illusion is by making their artifice recognisable. The films fashion this in their own different ways—A Clockwork Orange through its theatrical stylisation, which becomes almost pleasing to watch even in scenes which are perverse, Peeping Tom by being a film about films and implicating the viewer to side with the protagonist and his activities (seeing what he sees) and even sympathising with him, and Man Bites Dog, where the apparatus becomes central and the agents have to address the issues thrown out by it. Such films remind us of our complicity to cinematic illusion. This complicity results in the greatest voyeurism, which relies on the fascination with the real. Cinema hinges on voyeuristic premises because of the “fourth wall convention”, which has become popular in the genres of fiction cinema. So when self-reflexive films like the ones discussed come along, they disrupt this myth. Also the convention of a “passive” audience created through the point-of-view tool of cinema is too extreme a stand and is also a misappropriated generalisation. Point of view and identification maybe a constructed category, but it is in no way a forced one. There is a paradox in the viewing system—people “have sentimentalised and censored their own view of human life”, not recognizing that they themselves have engaged in it in some way or the other by becoming a part of the cinema-viewing process.

“We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms,” deplores the housekeeper played by Thelma Ritter in Alfred Hitchcock’s celebrated 1954 film Rear Window. She didn’t know even the half of what was to follow. Since that movie’s release over 50 years ago, the technical means of Peeping Tom-ism has exponentially exploded with camcorders, webcams, digital audio, video cameras on mobile phones, etc. and from a period of being the surreptitious Tom, we have become exposed by the same mechanical apparatus which we consider to be the reason for our pleasure, weakness, and paranoia in this world of stringent censorship.

first para itself doesn’t create a urge to go thru da whole writing of yours…