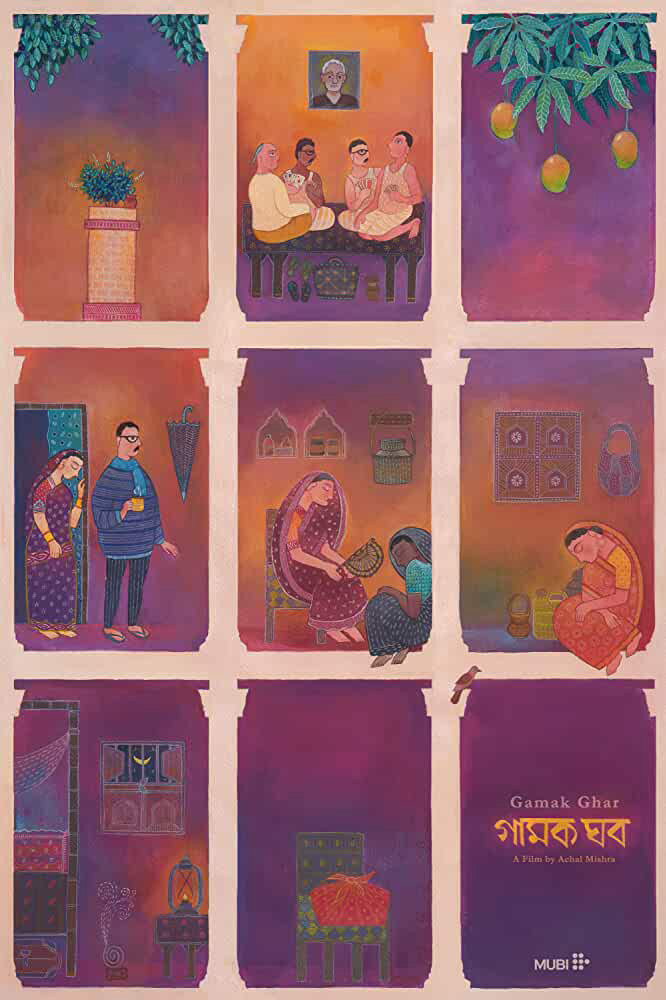

Photographs come alive in Achal Mishra’s Maithili-language film Gamak Ghar.

In an interview late last year, the first-time director spoke of early attempts at discovering his calling, his persistent interests in photography and writing and how films ultimately proved the perfect amalgam for them. There were talks of the need to move with the times and village homes all around his own near Darbhanga in Bihar were starting to be modernised. This pushed the director to return to his ancestral home and its stories, people and pictures, to reimagine, recreate and ultimately preserve through film a cherished time and place before time inevitably and permanently changed that place. In fact, it is time that determines the film’s structure, dividing the film into three visually distinct sections. The ancestral home and its changes are plotted against time’s unavoidable march as we see it at three different periods, each separated from the next by roughly a decade: 1998, 2010 and 2019.

Gamak Ghar’s form defies easy slotting. Mishra reconstructs his own and others’ memories and employs locals to enact moments as they are remembered. While depicting real incidents and attempting to safeguard through his film traditional ways and practices which are fast dying out, he also infuses them with creative and imagined elements. Thus, although based on real family members, the characters are not played by them. The house is real but its glory days are viewed not by means of actual old, salvaged footage but reconstructed in the present time. This combination of the real and the constructed, of truth and fiction also feeds into the ways in which the film plays with the ideas of past and present, stillness and movement, photography and film.

The film’s frames resemble photographs as a retiring camera captures unobtrusively, in its first section, the activities in different parts of the house as the large family comes together to celebrate a birth and prepare a feast. Eschewing close-ups, Mishra makes use of medium wide shots, some so static that detecting movement in them, in the form of the gentle sway of leaves on a tree or the soft billowing of smoke from an incense stick, is possible only after the image has been held and observed for a good few seconds. The camera doesn’t follow the characters; it remains still as they move in and out of the frame or busy themselves with activities just on its edge. Thematically too, they are secondary and we learn of the changes in their lives only in the context of the ancestral home. It is only when the family gathers for Chhath Puja festivities years later that we learn of the births and deaths that have occurred in the interim. The camera’s preference for the spaces of the home to the people who occupy it is unmistakable.

The frames in this first section with their 4:3 aspect ratio convey a sense of depth rather than width. The mise-en-scène is carefully designed and the visual layering of the foreground and background evoke the richness and variety of life and practices that were observed within the walls of the village home at one time. Moreover, these early images are imbued with a warm sepia glow which imparts to them a feeling of gentle nostalgia, inseparable from the remembrance of childhood and the family home.

The frames in this first section with their 4:3 aspect ratio convey a sense of depth rather than width.

The brightness of the first section fades considerably in the second and third while the frame becomes progressively wider, the visual differences indicating those periods’ distance from a happier, more carefree time in the past as well as the house’s relative and growing emptiness. There are mentions of floods which have wrought damage and parts of the house which have fallen into disrepair. Equally, the absence of people is felt; some have moved away to cities in search of jobs and have found functional flats in them to live in, while others have passed on. Shots from the earlier section are repeated and a lot of the same views of the house are offered. But the walls now have stains, the tulsi in the courtyard has withered. The house shows signs of age and neglect.

Moreover, even as Mishra’s frames resemble photographs, there are characters in them taking pictures themselves chronicling their present both through the images they capture and the devices they take them with, the changing technology yet another marker of the passage of time. Interestingly, we see a group photo being taken in the 1998 section while the product of that moment appears later tucked inside a photo album along with some of Mishra’s other early frames, strengthening further Gamak Ghar’s ties between film and photography.

The one character whose presence in the film comes closest to resembling who he was in real life is that of Mishra’s grandfather, playwright and actor Kedar Nath Mishra. His framed photo is seen in each of the film’s three time periods establishing both the connection with roots, and a sense of ancestry and long-standing tradition that extend their reach from afar. It is also an emblem of the past which has borne silent witness to the ravages of the years. In direct contrast to this idea is the centrality of the birth in the opening section and the repeated mentions of initiation ceremonies for young boys of the family in the later ones which hint at an opposing pull of the future explaining the film’s final moments.

Gamak Ghar is pieced together from old photographs, people’s recollections of local ceremonies, books found in dusty trunks and diary entries about daily errands and grocery—tangible and intangible relics from and of an earlier time and place. Through the medium of film, these relics find their place in and help to create a new, varied and more permanent record of that past.

Gamak Ghar is currently playing on MUBI India.