As a young girl, my grandmother loved to swim. She was born in what was then East Pakistan, in Barisal, where her family still lives. Even now her voice and laugh are a wheeze. They fill the room.

She is a large woman, with a loud voice often on the verge of tears. She was married off at seventeen to a man 10 years her senior. Her name was changed from Sujata to Sabita by her mother-in-law, who treated her unkindly. It was the way things were done.

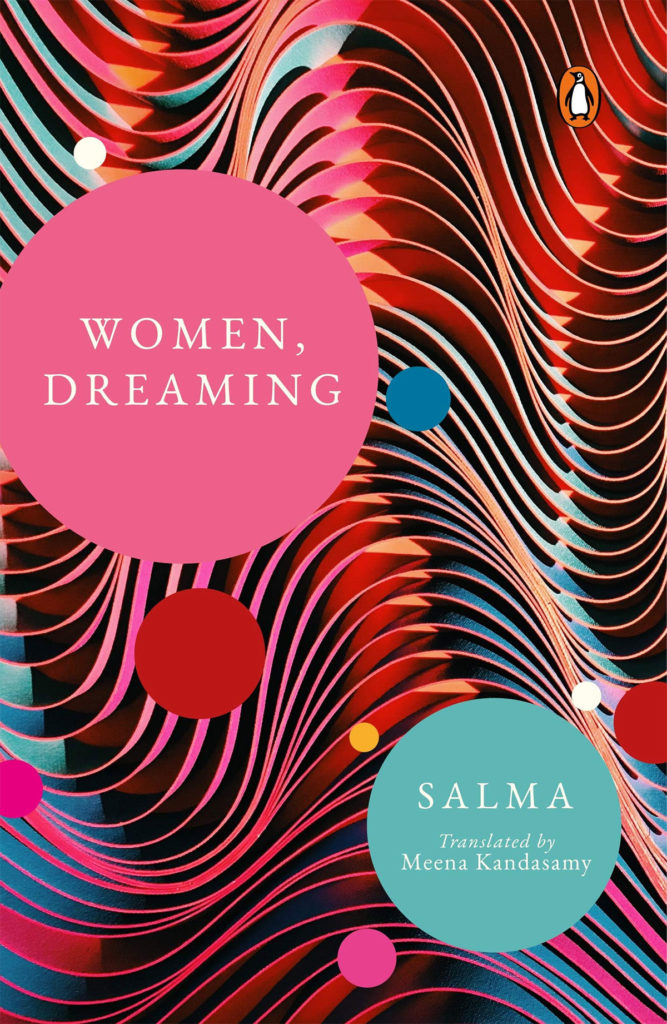

She is now eighty-four, a widow for over fifteen years, and seems to hold on to every stray hurt and rudeness that has come her way. It’s an exasperating quality that I find difficult to bear sometimes. In many ways, reading Women, Dreaming by Salma is a similarly and profoundly unsettling and uncomfortable experience. It is too real. Although worlds away from me, set in a small Muslim village in Southern Tamil Nadu, it brought me up close to familiar tears and hard lines.

Other reviewers have—as an aside to their praise for writer Salma’s novel and Meena Kandasamy’s deft translation—complained about the weeping interspersed through the book. It’s tiresome, they have said. I want to start here. It is tedious to be confronted with tears over and over. But so is grief, so is the act of crying—and so is the unbearable truth that many women, both from older generations and young girls today, have lives hemmed in by grief and by freedoms they dream of, and fall short of grasping.

I think of my grandmother; how her voice begins to quiver, cracking mid-way through a sentence; how every time I call, she complains that I don’t call her. How I take a deep breath to keep from snapping at her. It’s a mark of how utterly specific and universal Salma’s novel is. Her women, set in a very different milieu, are the women I know and have failed in my own life. The mothers and grandmothers, whose dreams were roughshod by boundaries enforced on women, and whose dreams for me I found too restrictive in turn. But, oh, Salma’s women dream.

Parveen, who opens the book, dreams of romance. Amina, her elderly blind aunt, remembers a childhood when she tried to grasp the shape of stars, and the only time a man touched her—a scene that reveals why Salma’s work has met abuse from conservative quarters that would deny women’s sexuality. Together they conspire to keep secret a burgeoning romance—within limits. Parveen’s sister-in-law, Mehar, and her mother, Asiya, weep over broken dreams. Mehar’s daughter Saji dreams of being a doctor. Still a child, she sometimes dreams of a car-ride with her brother and both her parents; a childhood she hadn’t known to cling on to. Meanwhile she grows skinny and isolated at her hostel, and her brother Ashraf, terrified by their authoritarian conservative father Hasan, runs away from his mother and bicycles around the neighbourhood.

It is a generational tale of women bound to each other by blood, marriage, and proximity—and how they each uphold various patriarchal mores even as they jostle against them.

The novel goes to surprising lengths to acquaint us even with the humanity of those we would write off as oppressors, without diluting the consequences of their actions. We are dropped inside the mind of a mean mother-in-law, Hasan’s bewilderment as he attempts to reconcile his rightful place as superior, male, patriarch with the lost love of his family, whose dreams he crushes in his pursuit of ibadat. Once a small boy who cherished dance routines and weekends at the cinema, he gives up on small joys. Above all, it is a generational tale of women bound to each other by blood, marriage, and proximity—and how they each uphold various patriarchal mores even as they jostle against them. It is, unquestionably, a feminist text that centres women, and the kind of translation we need more of in the mainstream.

The stories circle around each other, faltering and gathering pace—a stylistic choice translator Meena Kandasamy has elsewhere described as “a deliberately hesitant style that reflects the tiny, minute rebellions and transgressions women still manage to make in order to find their own independence and individuality.” I came to this book as an eager fan of Kandasamy’s writing, which is intimidatingly clever and always innovative, from the meta-narrative of When I Hit You and The Gypsy Goddess to her most recent Exquisite Cadavers, which unravels the creation of fiction itself. Here, it feels like she lets Salma be Salma. The prose is simple and unadorned, with moments of observation scattered throughout that are painful in their accuracy and clarity.

A few: Mehar’s love of a calendar from a grocery store featuring the usual Hindu Gods taped over with a white paper and a photograph of her children. Parveen’s recollections of posing for white tourists, thrilling at the attention. Women clamouring over WhatsApp-forwarded porn. The venomous contempt certain men cultivate towards their wives. The guilt Saji feels towards her future escape, knowing that her mother is denied it. Men’s neglect of petty things like time. I recognised the stakes of fighting to wear light-sarees in the form of childhood memories of a slap for wanting to wear jeans with holes at the knees.

Perhaps you will recognise these women. Perhaps they are women whose fragments live in your mothers, grandmothers, yourself. I did. I found it to be largely a feminist text of dread. It ends perched on a precipice. I wished I knew more about the women and the texture of their dreams. There are glimpses when the text glimmers with air and space such as the moments in Saji’s terrace, and women forwarding porn to each other. Freedom for women is still hard won, and fought for. I’m still thinking of what happened to the ones in the book, days after the words stopped. They are not so far away from us, these women dreaming.