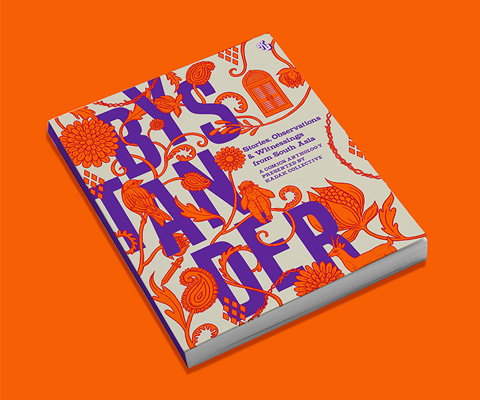

Bystander is an ambitious new project conceptualised by the minds behind Kadak, an inspiring collective of South Asian women who work with graphic storytelling that traverses the personal and political, questions culture, and examines subculture.

An anthology of graphic narratives, Bystander will gather works created by a diverse group of over 50 South Asian creators from 13 countries. The project aims to curate and present narratives about geography and gender, identity and self, boundary and exclusion through the lens of the experience of the ‘other’—the bystander.

The Kadak Collective and the creators involved in the project are currently using the Kickstarter platform to gather funds to produce the Bystander anthology. We spoke to Mira Malhotra, founder of Studio Kohl and part of the Kadak Collective, and Sabika Abbas, a performance poet, alternative educator, and one of the editors working on the anthology, about the massive scope of the project, how they’re putting it all together, and what their goals are for Bystander. Read on for excerpts from the interview—

Bystander. Image courtesy of the Kadak Collective.

Bystander is a truly ambitious project. Could you tell me about how the idea for the anthology came together?

Mira: The idea came about a little while ago, when Kadak was just starting to get recognised as a brand. We had released a few zines and been a part of zine fests and exhibitions, and we were wondering what the next step for the collective should be. It was around then that Akhila [Krishnan] had attended a Kickstarter workshop in the U.K. She was quite excited about the idea of doing a crowdfunded project, and asked us whether we’d be interested, as it would be a good way of doing something big. We felt that a crowdfunded project would work well for us, as we have a considerable network that we can reach as a collective, and the fact that a bunch of women were creating something together would be so different from what you usually see in terms of [creative projects from] South Asia. All of the big design projects that have come from here [in the recent past] were led by a bunch of dudebros, to be honest (laughs).

(Laughs) That is true. I’d love to know more about the conversations that led to the idea behind this anthology. It has a very broad scope, with over 50 contributors from South Asia and the South Asian diaspora contributing to this project.

Mira: All of us were talking along the lines of geography, gender, spaces, but we found that there was already quite a bit of work done around those themes in the last five years. We felt that we needed another angle that we could explore. Aarthi came to us with the idea of a ‘bystander’, and I thought that was very cool. These days, a lot of us are having to question our privilege, especially with the idea of intersectionality entering more and more feminist conversations. We thought about what it was like to be privileged in one way, but not be privileged in other ways, to be able to negotiate your own privilege. The idea was: what happens to the other? And the conversation really expanded from there. What do we expect from people with privilege? What about situations where you can intervene, but you don’t? What if you can’t intervene, for some reason? How do you engage with a situation unfolding when you aren’t privileged enough to participate in the discourse? Another thing that Aarthi pointed out was that there is no proper translation for the word ‘bystander’ in most South Asian languages.

Sabika: When Aarthi wrote to me and shared her idea with me, what got me really excited was the fact that for me, the idea of a bystander is something that I’ve explored in my own work and thought about and had tensions with, actually.

In what ways?

Sabika: When mob lynchings are happening in the country, the first thing that people ask is: what were the people standing around doing? Why couldn’t they intervene? Same with road accidents; people don’t come to help. When I read the brief that Aarthi had sent, the nuances of the idea of a bystander was what was so attractive and unique about this project. We weren’t interested in conversations around a unilateral narrative of a bystander. You could be a bystander because your identity makes you a bystander; because your fear of becoming the victim makes you a bystander. Your physical disability could make you a bystander; not knowing a particular language, being a migrant, belonging to an ethnicity could make you a bystander. The idea of a bystander is fluid and intersectional and has many aspects.

Was it surprising for you to discover that there is no direct translation of the word ‘bystander’ in most South Asian languages?

Mira: It wasn’t exactly surprising. Maybe it speaks to the cultures that we belong to; the fact that it is maybe permissible to not do anything in a given situation. And this is not just limited to public spaces. One of the contributors put forth the idea that you can be a bystander to your own life, where other people make all your life decisions for you. As a woman, that’s something I can really relate to. You’re constantly told that you have to get married, have a baby, you keep hearing a lot of things like that. No one asks if you want to do any of these things, ever. You’re just asked when you’re going to do these things, because it’s expected of you.

Once you had decided on the theme, how did you go about selecting the contributors for the anthology?

Sabika: The list of contributors initially consisted of various people that the people in the Kadak Collective already knew through their networks. What’s very important is the identities of the contributors. They don’t just practise different art forms; they also have their own politics and positions, which gives a new perspective to the idea of a bystander. The contributors include Dalits and Muslims and people from different tribes, and they’re all spread out over 13 countries. When we asked the contributors to send us their concept note about how they see or they want to interact with this theme, we [in the editorial team] were beyond surprised by the range of the ideas that came in.

Mira: (Laughs) I was quite pleasantly surprised to see that designers, artists, and illustrators are thinking about politics, and it’s amazing.

“The contributors came to us with so many perspectives—development, tribal rights, environment, ethnicity, migration, even the idea of looking at yourself as a bystander.” Image courtesy of the Kadak Collective.

Sabika: It is amazing, because they came to us with so many perspectives—development, tribal rights, environment, ethnicity, migration, even the idea of looking at yourself as a bystander. Since there were so many different kinds of ideas and conflicts to consider, besides just the idea of bystanders in public spaces and how spaces themselves create bystanders, we decided to group them into sub-themes. We realised that there were some ideas about the self—self-reflection, the gaze of the self, self-distancing, and how we see the self as the other. There are pieces that deal with the idea of the bystander as a philosophy or a perception. What makes someone a bystander? Who cannot be a bystander? There are concepts around the idea of being a bystander with regards to your immediate surroundings, physical and sociopolitical.

Some artists are keen to explore the haptic and audiovisual aspects of being a bystander. There are pieces that deal with the politics of being a bystander, from inside and outside political movements, and the expectations that people have of bystanders in that context. Also the political calling out of the bystander for their inaction. We also explore the societal aspects of being a bystander, the idea that society itself creates bystanders to oppression. Then we have being a bystander in a relationship, or certain relationships themselves being bystanders. Queer relationships, hetero and non-normative family structures, friendships, comradeships that create bystanders within and outside themselves.

There were also concepts that came in that explored ideas that we didn’t think of ourselves. How do we see nature? How we deal with being bystanders to the destruction of the environment and wildlife, how so many communities are forced to become bystanders to the destruction of their homes and rituals in the name of development. Mental health is also a crucial theme that is explored—how it makes people bystanders to experiences and ‘normative’ activities; how anxiety, depression, trauma, and stress can make it difficult to intervene.

It sounds like you have been working on this anthology for a while now. How much has been completed and where do things currently stand?

Mira: We started work on the book in February 2019, as we began to understand how to make sense of the theme. We started putting together our list of contributors and looking at the different countries that they were from. Our external editors Sabika and Gopika [Bashi] came on board after that; they brought in a very different perspective. They have a lot of experience when it comes to social organising, activism, and campaigning. All of us at Kadak really needed and appreciated what they brought to this project. We had to make some tough decisions, which came from wanting to be as inclusive and comprehensive as possible. At this point, we have all of our contributors’ concept notes and everyone has committed to this project. All we are waiting for now is for the project to get fully funded on Kickstarter so that we can start making our comics and illustrations and designing the book. We’re doing our best to make the crowdfunding process as ethical and transparent as possible.

Do you have a launch date planned for the book?

Sabika: We’re looking to release the anthology in January 2020. Something I’ve been thinking about lately is how crowdfunding makes projects a lot more democratic. For example, seeking funding from a space or organisation that has a particular agenda or ideology would not work as well for something like Bystander, which is important to consider in terms of the politics of a project like this.

The creators and contributors talk about Bystander.

What would you like people to consider or feel after reading the perspectives presented in Bystander?

Sabika: In our conversations [about the book], there has been no big political narrative-based intervention into the idea of a bystander. It has always been about calling out the bystander for their lack of action. Bystander is going to offer a novel narrative that will hopefully make people rethink the idea of a bystander.

Mira: What I find interesting is that there is a lot of writing and a lot of journalism out there that talks about many of the issues presented in the book. But bringing these issues to light in this particular format hasn’t really been done before, especially in the South Asian context.

Why did you choose to highlight these stories in the form of graphic narratives?

Mira: In the work that I’ve done for organisations that work in the social good space, I still have to justify a lot of my decisions, for example, using a particular type of illustration of a person or a certain skin colour, etc. They want to do what’s right, but they’re still not clear on what the consensus is. With Bystander, in a lot of ways, we’re starting from scratch in this regard. Thinking about the kind of visuals that will be generated as part of this project, we could actually use them as a sort of model for future communication on these topics.

Sabika: We’re also creating a pool or comradeship of South Asian artists. A collaboration on this scale also gives way for further collaborations down the line.

Do you feel like telling these stories through the medium of comics may also make them accessible to people who may not otherwise read or talk about these subjects?

Mira: Absolutely. You can talk to a younger audience, for example. Someone who inspires me in this regard is Sharad Sharma, who goes from village to village teaching people how to make comics. That allows the people in the villages to raise their voices and talk about the issues that they face through comics in a very nuanced way, which in many cases results in those issues being taken seriously. If you have to read a 10-page document that is all text, you’re probably not going to get through it, but if you have to read a comic about the same thing, it’s so much more engaging. It makes it easier to get the message across and you cut out a lot of the noise. You give the readers something besides just the information, you give them an experience.

There is also going to be a version of the Bystander anthology created for the Web. Will there be different kinds of stories presented there?

Sabika: Yes, they are two distinct anthologies, with two different sets of contributors. We have a lot of visual artists who enjoy using the medium of the Web, and we are excited about that. The Web version of the anthology will be free to view and reach a wider audience as well, and will also bring an element of accessibility for our readers.

Mira: The Web version of the anthology will make full use of the medium. There are many contributors who want to tell their stories through sound, or videos, or GIFs, or just taking advantage of the plastic nature of the Web.

The creators are looking to gather funds to produce Bystander through a crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter. Graphic by Kritika Trehan.

How have your own practices been influenced by working on a project of this scale, with such a wide range of contributors?

Sabika: Gopika and I learn new terms and ideas every day related to visual art and graphic design that we’ve never heard before in our lives (laughs).

Mira: (Laughs) Gopika was telling me the other day about how we should have feminist principles guiding the way in which Kadak functions. We’d never considered this before because we have never functioned as an organisation. Sabika blows our minds away sometimes with the perspectives she brings in and the conversations she encourages us to have. For us, just working with the editors and all the contributors is like being in a different world sometimes, and in the best way. It’s been a very beneficial experience.

Are you looking at taking the project to offline spaces, maybe at galleries or through performances, etc.?

Sabika: We’ve actually planned workshops throughout the year, across cities. We will have resourced people conducting workshops around the theme of a bystander, interacting with the theme in different ways. Of course, all this depends on whether we get funded (laughs).

Mira: Yeah, all of our plans depend on that (laughs).

I’d like to end this interview by coming back to the idea of a bystander. For many of us, social networks are our only source of news and opinions—how would you define a bystander in the context of echo chambers created and perpetuated by social media?

Sabika: One of the reasons that I started performing my poetry on the streets is that whenever I was invited to give lectures or talks or be a part of panel discussions, I would regularly see the same faces. Always. Similar faces asking similar questions, using all the jargon that you have access to if you come from a particular academic background. Through my street performances, I also have a lot of conversations with people who come to watch me perform.

It’s true that echo chambers exist on social media. I do think that there are groups of people who enjoy having fancy, ‘intellectual’ conversations, who are bystanders to the things that happen on the ground. I think the echo chambers are a bystander to on-ground politics.

Mira: I feel like echo chambers are a relatively new phenomenon that we don’t quite know how to grapple with yet. Platforms like Facebook and Instagram are themselves bystanders to the echo-chamber phenomenon while at the same time being the ones creating it. There is no action being taken against the toxicity that these platforms generate or the targeting that happens through them. They wield a lot of power but they let this happen, all in the pursuit of profits.

Sabika: The networks and the diversity that the Bystander anthology has enabled will maybe challenge these echo chambers in some way. The contributors will bring not only their work, but the work of all the other contributors to their own networks. When we move the cameras and hand over the mics, I hope the echo chambers will slowly fall away.