In January 2015, following intensifying protests against his book Madhorubhagan (tr. One Part Woman), Perumal Murugan declared his death as a writer.

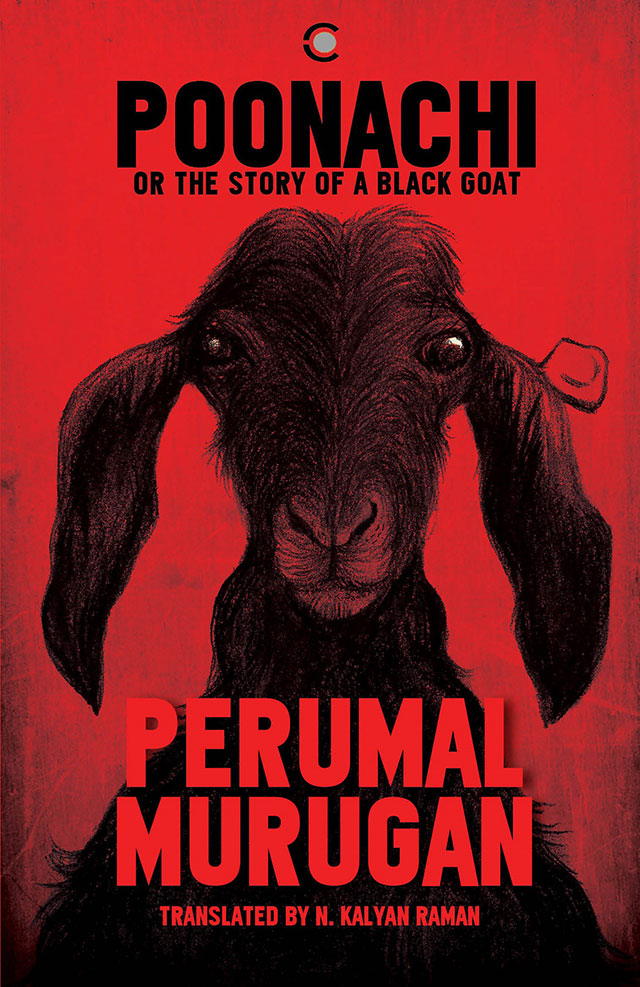

Poonachi, published in Tamil in 2016 and in English in 2018, is his first novel written since his dramatic declaration, marking his resurrection from self-imposed literary exile. In circumvention and defiance of censorship, he writes in his preface to this book that fearful of writing about humans and gods, he has chosen to write about animals instead. He proceeds to explain, “There are only five species of animals with which I am deeply familiar. Of them, dogs and cats are meant for poetry. It is forbidden to write about cows or pigs. That leaves only goats and sheep. Goats are problem-free, harmless, and, above all, energetic. A story needs narrative pace. Therefore, I’ve chosen to write about goats.” One may well expect such a work then, to be a fable along the lines of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, drawing barely disguised analogies to human behaviour and predicaments, and yet, Poonachi is more than this.

The protagonist is Poonachi, a black (doe) goat who comes as a fragile baby into the lives of an elderly human couple like a miracle, and the story follows the course of her life. The unnamed old man and woman (who significantly belong to the Asura cult) look after the motherless kid like their own progeny, having been entrusted with her care by an imposing stranger they come to refer to as ‘Bakasura’. The narrative traces Poonachi’s growth into maturity, affectionately dwelling on her small helplessness and later unabashedly depicting her sexual awakening. Being a doe saves her from the cruel fate of neutering/ slaughtering/ sacrificing that is the lot of the bucks, but makes her vulnerable to the attendant tribulations of pregnancy and motherhood, whether it is the exhausting nurturing of her numerous kids or painful separation from them. Her status as a miraculously fertile, high milk-yielding, seven-kid birthing mother further victimises her. But in the midst of short-lived joy and prolonged misery, Poonachi snatches her little bit of happiness in Poovan, the gentle and loving buck she encounters twice briefly on ‘pilgrimages’ to the old couple’s daughter’s home.

The selection of goats, known for their vitality and sexual energy, enables the author to fearlessly express their frank sexuality, investing it with emotions but not with the customary limitations that inform ‘civilised’ human behaviour. Accepting multiple sexual partners here is not sinful, but neutering a highly sexed buck is suffused with a tragic air and followed by repentance. The description of Poonachi’s miraculous union with Poovan is charged with the sexual intensity and tenderness generally associated with human behaviour. Her attainment of puberty, her menstruation and irrepressible sexual longing and first dissatisfying sexual experience, the exhilarating and draining experience of motherhood—all serve to build an unusual bildungsroman and a biography, of a female animal. All of this is, in true Perumal Murugan style, unsentimental and earthily matter-of-fact, drawing attention to the helplessness of the female body and the multiple and violent demands on it, whether by nature, or the community. As the omniscient narrator dips into the recesses of Poonachi’s mind, whether in the form of the defiant independence of her thoughts, the vividness of her dreams, the poignancy of her desire for Poovan and its attendant jealousies, or her ruminations on the nature of all existence, it is difficult to differentiate between the human and the caprine.

However, despite some similarities between the conditions of goats and humans discernible in the story, Poonachi is not primarily allegorical, but accords animalkind the dignity and depth of feelings that they are rarely manifested with in literature. Indeed, the differences between the species is pronounced, as we observe the many ways in which the humans, including the well-meaning elderly couple rope in, couple, mate, ‘sacrifice’, or dispose off their cattle for their own human interests, whether profit or sheer survival. In one instance, the couple’s good fortune comes at the cost of Poonachi’s exploitation and both are depicted as unable to sleep for contrasting reasons. Ultimately, goats and humans are unable to communicate and positioned differently along a fixed hierarchy, and therein lies the source of much of Poonachi’s suffering.

The reader also catches glimpses of such hierarchies that are an integral part of human society. In one extended sequence in the novel, the author describes the mandatory procedure for citizens and their pets to get their ears pierced and slyly slips in a comment on the surveillance state. As the elderly couple fearfully consider this obligation, the narrative tells us, “The regime had the power to turn its own people, at any moment, into adversaries, enemies and traitors.” It then gestures towards the paranoia of the state, as the old woman says: “Goats have horns, don’t they? Suppose they get a little angry and point them at the regime? Such goats have to be identified, right? That’s why they all have to get their ears pierced.” And then ensues a discussion on the wisdom and farsightedness of the government in issuing such a mandate. At another place, a government official impresses upon the couple that the superpowerdom of a nation depends upon the fecundity of its goats. Further general observations include: “Everyone was well-versed in how they were expected to behave towards the regime. They had mouths only to keep shut, hands only to make obeisance, knees only to bend and kneel, backs only to bend, and bodies only to shrink before the authorities”. This is the closest the text comes to a satire on the human condition, with generous dollops of the absurd. Though such statements are few and far between and may even appear a tad contrived, they still show that the powerless or the silenced should not be mistaken as acquiescing.

There is much to be learnt from Poonachi, whether about the transience of life or the deeply entrenched inequalities within humans, or between humans and other creatures, which are too routine to be majestically tragic. It is also about the briefness of miracles, miracles turning into curses, and the inevitability of suffering, separation, and death. Through its humble cast of characters, the slim novel, as sparse as its setting, explores needs and instincts essential to all living creatures—hunger, safe shelter, affection, or sex. As the translator N Kalyan Raman summarises, this book, probably the first Tamil novel about animals written for adult readers, “makes us reflect on our own responses to hegemony and enslavement, selflessness and appetite, resistance and resignation, living and dying”. And in that sense it is not just the innocent story of a black goat, but a moving and universal political story of relevance to all of us. Perumal Murugan brings his previous strengths as a chronicler of the minutiae of rural life and nature, and the sensitive portrayal of female characters, together in this novel and forays into a new direction marked by a refreshing lack of anthropocentrism that is a fitting need in times when human freedoms and desires are so under siege and humans begin to identify with animals.

[Context; ISBN 9789386850492]

Incredibly helpful review. And very interesting. I loved Poonachi and am thinking about including it as a primary text for my research in Literary Animal Studies. Your review assured me that there are so many other themes that can lend credence to my work if I choose Murugan’s latest. Thanks a lot!

Hey, glad you read this and it did something for you. Thanks for bothering to let me know. :) Also, best wishes to you for your interesting research project!