Everyday was the same, but today felt different. The night before, Tara hadn’t slept well; something had bitten her. After many failed attempts at rest, she awoke and faced the mist lingering in the valley. The morning light crept up, up behind the mountain, flicking its peak and sweeping into the clouds that gathered mist and hovered below. The light emerged a pale yellow, then a tangerine pink, then it burned a bright, strong yellow. Itching her thighs, muscles stiff, Tara raised herself from the stone bench that lined the veranda of her home and began her day.

“There’s a lot of work to finish up at the post office today,” her husband said before leaving for work. She would have to buy what she needed from the main road.

Usually, Tara swept the floor when her husband walked to the post office, but today Tara pulled the mattress and blanket into the sun. She gathered a fistful of baking soda and salt, sprinkling it on the bedding that basked in the morning light. The fleas will die this way. She wrapped her dupatta around her head, tying it into a fierce knot, after which she carried an empty bucket to the outdoor faucet. Squatting, she dipped her clothes in water, rinsing the soap she had soaked them in.

“Pradhan Madam!” A man called out from the road above. He was a tiny man with cheeks that caved in.

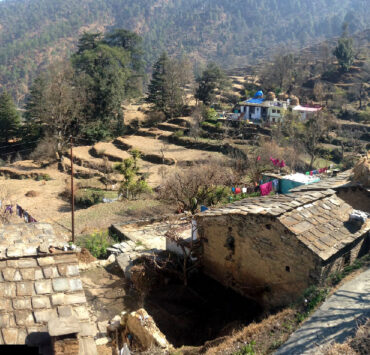

The morning light crept up, sweeping into the clouds that gathered mist and hovered below. Photograph by Nikhil Gulati.

“Namaste, Sharmaji. Come, come.” She brewed him a cupful of tea so that while he drank she could tell him what needed to be done. “We need another wooden shelf,” she used her hands to measure, “about four palms wide,” bent her elbow, “and three forearms long.” Sharmaji nodded, pulling out a small packet out of his front pocket. “How long will it take?”

He emptied the contents of the packet into his left palm, grinding it with his right thumb, taking his time.

“Today only, Madam. It will be done by dusk.”

Another man arrived to fix the electricity. He brought his own ladder, which he climbed to reach the wires hanging above the house.

While the man on the ladder searched for fizzed wire edges Tara went back to her washing. She was unable to ignore the sawing wood; this time of day was usually silent. Whish-whoosh, whish-whoosh, whish-whoosh. The sounds of wood would continue till dusk, as Sharma had promised. But now, it was still morning and Shyama was getting ready for school.

“Shyama, hurry. We’ll be late!” a group of her friends called from the road.

“Coming, coming. You have a call.” Shyama handed Tara her phone before scurrying off to join her friends.

It was Tara’s son, calling from the big town. He wanted to hear his mother’s voice, to tell her he was studying for his exams, that he was ready for S.S.T. and English, but he still needed to work on preparing for Maths. Would she help him? Would she visit?

“Of course I will, my love. I’m coming to see you next week, didn’t Nani tell you? We’ll work on Maths then. Give your Mammi a puchchi, a kiss. I love you, my moon.”

Another reason for yesterday’s sleepless night was Tara’s worrisome nature. When Tara went to the big town to visit her children, who would look after her husband and Shyama? They look to me for support. If I’m strong, they’re strong. They depend on me for everything.

That evening her husband and niece would assure her that they could take care of themselves, that she needn’t worry, but Tara would remain torn—her family was here and not here. The schools in the big town were better than those in the village. Education is the only way they’ll have a better life, even if the fees are greater, even if they are farther from me. Sacrifice, she believed, was the foundation of her motherhood. That evening, she would come to terms with her visit to the big town, but now as she hung out the washed clothes to dry, her mind raced with apprehension.

Whish-whoosh, whish-whoosh, whish-whoosh. Sharma occasionally sprinkled the contents of his little packet into his palm, ground the powder, and popped it into his mouth with familiar flourish. The electrician meddled with the wires, he asked for a cup of tea, and Tara prepared some more for him. Suddenly, one of her trees shook with the weight of a few birds, pecking on a cucumber, now ripe. Tara picked up a few stones and hurled them at the birds, who flew away, caw-cawing in retribution.

Tomatoes, salt, tea. Ready with a mental list of items to purchase, she walked up the pebbled path that snaked past the sloping hills, past the primary school (children were playing badminton with their teacher), past the valley dotted with small houses made of mud and straw, past the pine trees, erect and dripping with resin (she picked up a few pine cones on the way), past the howling monkeys bouncing on the pine branches, peering curiously. Look straight, look confident, they won’t disturb me.

Upon reaching the main road, she saw a group of men lounging idly, eyeing her as she walked by. She was the Pradhan, but she was still a woman, and oh, what a woman. Hair that shined in the morning light, ruddy cheeks, small eyes, and full lips. Their gaze, she knew, rested on her. Sometimes her husband sat with these men for a drink and a game of cards. They called her bhabhi, sister-in-law. Tara strode with a confidence foreign to them, not found in their women. Tara passed by the larger store, towards a smaller one across the street.

“Namaste, Pradhan Madam. You bless me by coming to my store. What can I get you?”

She recited her list and one by one, the items filled her bag.

Tara opened her purse. “How much?”

“Arre, how can I take money from you? You’ve done so much for the village already. Please, consider this my gift—”

“No, I won’t hear of it. I’m taking your items and I’m paying for them. And that’s that.”

He was a good man, this shopkeeper, not like the big store owner with the wandering eyes and slippery smile. On her way home, walking down the pebbled path, she pondered. Why can’t men respect women? Is it so hard to respect another human being? That’s what our culture speaks of, respect. We are supposed to cover our heads out of respect for our elders, we are supposed to touch their feet. We are supposed to fast for our husbands’ long lives because we respect them. We aren’t even allowed to say their names out of respect. But this issue of respect for women, something needs to be done. Yes, I have to do something. But what? And how?

To accept injustice was not in her nature. Tara itched to change the wrongs she saw, but felt torn between performing her role as mother and wife and pushing what her role as Pradhan stood for. Leading at home was easy, working with people she knew was doable, but in these men who challenged her authority, who degraded her with their eyes and thoughts, respect was missing. Something needed to be done. But what? And how? Her mind was blocked with walls she wanted to break, her thoughts cluttered with questions, when she arrived home.

Phut, phut. Phut, phut. Sharma pounded nails into the leg of the shelf. The electrician had left. Tara would pay him later.

“Sharmaji, you want more chai?”

Phut, phut. “No, I’m okay.” Phut, phut.

“Sharmaji, I want to ask you something. Do you think the men respect the women here?”

Phut, phut. “What sort of question,” phut, “is that?” phut, phut. He wiped his brow with the sleeve of his shirt. “Of course I respect women.”

Ready with a mental list of items to purchase, she walked up the pebbled path that snaked past the sloping hills. Photograph by Nikhil Gulati.

“I’m not talking about you. I mean all men. In general.”

“What do you mean ‘all men’? I can’t speak for all men. I can only speak for myself and I can tell you that I respect women. Where is this coming from, anyway? Did someone say something to you?”

“No, no one said anything.”

“Did someone do something then?” He sat down on the unused planks of wood.

“Well, yes and no. No one said anything. I went up to shop up on the road and the men were looking at me.”

“Looking? Now what’s wrong with looking?”

“They weren’t just looking. They were… thinking dirty thoughts, it was disrespectful.” How can one describe the feeling one has to experience to know?

“You don’t know what they were thinking. What, Madam, now you sound ridiculous. You are an important woman, a big woman. You are the Pradhan. If you start thinking this way, what kind of nonsense will the other women come up with? Men can’t look now? Should we close our eyes when women walk by?

“You people are strange creatures. First, you don’t want to wear a pallu on your head, so that we can see you. And then when we see you, you don’t want us to look.” Sharma shook his head, laughing to himself. “What has the world come to.”

He wiped his hands on the thighs of his pants. “Chalo, your shelf is done. One thousand rupees.”

“One thousand? You’re mad or what, last time I paid you five hundred.”

“Madam, the rates have gone up. Times are hard, living is more expensive now, no?”

“Scoundrel,” Tara stood up, hands on her hips, “I’m not paying you a paisa more than five hundred. Get up, get out of my house. Lecturing me on respect. You don’t have an ounce of respect in your bones.”

“You think you can speak to me with such foul tongue? And I’ll take it because you’re Pradhan? Just wait till your husband gets home, he’ll teach you a lesson you won’t forget.”

“What?” Tara spit on the ground in front of Sharma. “You think all men are like you, idiots who drink and beat their wives? Uneducated filth. I don’t need you or anyone else insulting me under my own roof. Get out, swine. I said get out!”

“I’m leaving, I’m leaving. I’ll settle my accounts later.” He spat on her wood as he turned. It left a red splotch. “Respect,” she heard him mutter, “she talks about respect and look at her, filthy mouth.”

Looking at the hills ahead, with a heavy heart, Tara sat on the stone bench. The forest stood mute, resolute in its steadiness. Nothing fazes those trees, rain or heat or snow. I have to be strong, like them. Tara had done the right thing, that she knew, but she felt so tired and so small.