Are songs and albums to be understood as narratives, the words to be listened to from beginning to end, to make one ask eventually: what story are they narrating and how is the music facilitating them?

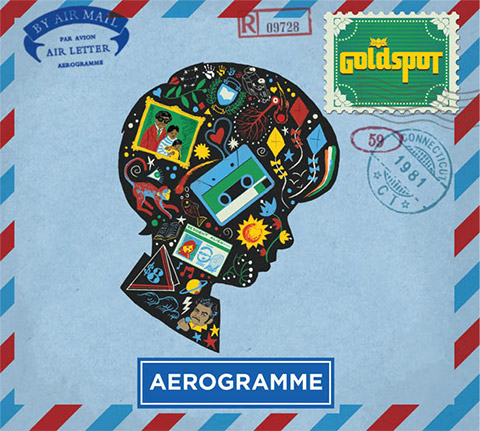

New York-based indie rock band Goldspot is no stranger to listeners in India. Their latest album Aerogramme, released by Sony Music in India this month, narrates frontman Siddhartha Khosla’s parents’ shift from India to America. Living in penury during their first few years in the U.S., they had to send their newborn son back to India to live with their relatives; he was back in America a few years later, once they were able to support themselves and him.

Aerogramme is Goldspot’s third studio album.

If the narrative aspect is ignored, this is just a set of catchy pop tunes, more interesting for being deeply influenced by older Hindi film music but eventually repetitive and hence, tiring. One could say it’s the other way around: older Hindi film music deeply influenced by American pop. It’s a sound I haven’t heard before. Indian rock musicians seem to be too embarrassed to use their vernacular influences if they have any; film music composers usually go another way—Hindi film music influenced by rock—but other than a few instances, such as Amit Trivedi’s compositions for Dev.D, the music doesn’t mesh as subtly as it does here.

Early in the first song, ‘Abyss’, we hear a rich harmonium/accordion sound, accompanied by a standard beat and followed by a simple up-down vocal style, with minor variations. Listeners of Indian film music will notice Khosla smoothly mixing vocal styles from Indian and American popular music. “Time was a film run backwards / Through my hands / … / … Castaway”: the italicised portions sound very familiar. But this is not fusion. We don’t notice the joints, the points where the vocal styles are fusing, don’t hear a collaboration-in-spite-of-differences. The vocal style wouldn’t strike a contemporary listener of pop in the West as unusual, though the accompanying arrangements might.

It is by listening to the songs as separate (but coherent) incomplete narratives set to music, rather like Indian film music, that the album comes into focus. The songs are sufficiently detailed and unified for the listener to glean the outline of a particular story, though there is no desire to complete the story in each song: the details, the outline of a story, the singer-narrator’s “emotion recollected in tranquillity” are sufficient.

‘Evergreen Cassette’ has Khosla singing in an endearingly filmi style, about his mother sending him cassettes with stories, “evergreen hits, lullabies, and everything [she] had to say” from America to India. When he sings, “If time, time could be bent with a drop of a tear / You’d see it rained in our house for a year / This is the sound of the beating you’d hear”, we realise that we’re hearing it. In ‘New Haven Green’, the shift from India to America, which, in a way, makes this album possible at all, is narrated. There is a point at which the subject of the album and Khosla’s birth itself is addressed: “Can we go back to the New Haven green / Two of you turning into three? /… / Tell the entire story again.” The “two of [them]” do “[turn] into three” in New Haven, but the third—the child—is sent back to India.

‘Resident Alien’ is set in America after the child’s return: “And in the left sleeve, I found a green card / And her name read like a new word / But below it in the lettering / What I found was so unsettling” because “She was a resident, resident, resident alien…”. The beat in the background is almost comical, the kind that would play in the background in different comic situations in older Hindi films. It made me think of a hero chasing a villain in slow-motion. This kind of mismatch—which may not be obvious to the non-Indian listener—is a regular feature of the album.

Many of the songs on Aerogramme have the singer seeking to recall and narrate the past. The first song has the line: “You’ve been closing in on me day after day”, where ‘you’ refers to the subject of the album (his parents, the past). “Turn the clocks back… I’m going back to the start”. Later in the song, the ‘I’ changes to ‘we’ (“we’re going back to the start”); “we” could be him and his parents or him and his listeners. What is going to take us back to the start? The songs themselves.

In ‘Evergreen Cassette’, he sings: “See, mother, I believe that half of everything I hear is true / Between you and me, I believe the anecdotes too”, and then, after a pause: “If they get you through”. The songs seek to get him through the past into the present and to get his past through to us. The past fused and reformed into a musical work that is catchy and eventually repetitive like much pop music, but moving without being sentimental in its recall of the singer’s own past, biographical and musical, which his present too is composed of.

All in all, Aerogramme is sure to set off echoes—cinematic, musical—in the minds of Indian listeners, and given how music and films are inextricably intertwined with the lives of so many of them, it might prove to be biographical as well.

[Sony Music India; October 2013]