Megha sat across from Ashok, watching him eat the avalakki she had prepared. He took a second helping, which meant that he liked it. She had gathered that much in the few weeks that she had been married to him.

Ashok finished his breakfast and got ready to leave for work. “Bye,” he said, and opened the door. She wished he would give her a hug or a peck on her cheek before he left, like she had seen people do in movies, but she was too shy to ask. She waved like she was rubbing a stubborn stain on a window, and closed the door behind him.

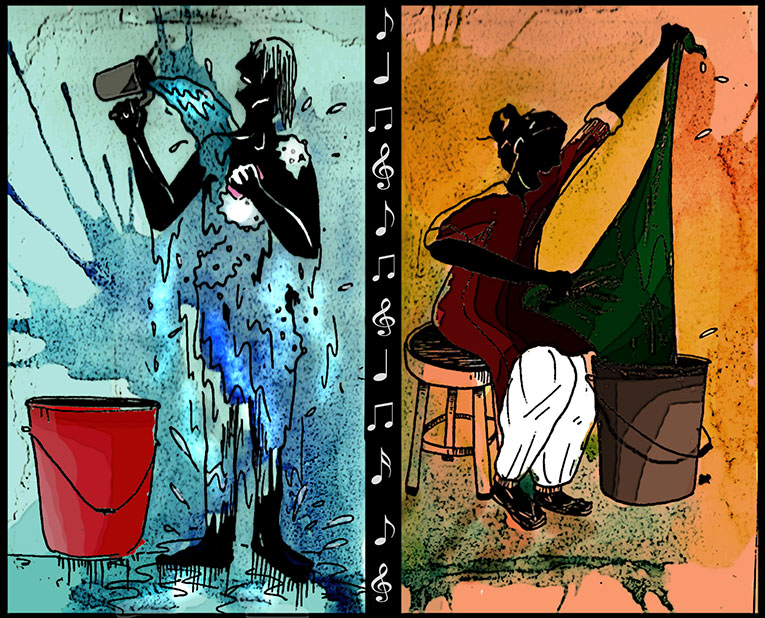

Megha opened the windows, and lit an incense stick to nudge out of the house the smell of onions from the morning’s breakfast. She straightened the sofa coverlet, folded the newspaper, and washed the dishes. She hummed as she picked up a bucket of unwashed clothes and went to the bathroom. As she stirred up the suds in the bucket, she listened, as always, for the man next door singing in his bathroom.

Sure enough, he was there, taking a bucket bath and singing. It was ‘Tum Jo Mil Gaye Ho’ today. The soulful song sounded lovely in the man’s voice. Though his voice was gravelly and not exactly pleasant, he knew his music. He was in full command over the notes, and his voice soared effortlessly over glissandos. He sang with such passion and depth of feeling, that any shortcomings in his voice were easily overlooked.

Megha had seen the owner of the voice several times before. He lived in the apartment next to theirs, and she had worked out that their bathrooms were adjacent to each other. He was a serious-looking man with a pencil moustache, and dark, brooding eyes. It was easy to match the voice to him, but it was next to impossible to relate the passion with which he sang to the serious, stoic person that he seemed to be.

She loved listening to him sing as she washed the clothes.

“… ke jahaan mil gaya…” sang the man.

Megha hummed along, busy with the clothes, careful not to make too much noise and indicate that the man had an audience. The man’s voice faded, and he paused for a minute. He then started singing ‘Deewana Hua Badal’. Megha grinned. Her father’s favourite song. She chuckled as she thought of the song’s picturisation: the hills of Kashmir, the dashing Shammi Kapoor, and Sharmila Tagore smiling her lopsided smile to show off her dimple in the best light. Megha was completely immersed in the song, and in her daydream, had actually gone off to Kashmir.

Just then, the man paused. Instinctively, Megha picked up from where he had left, and she continued the song, full-throated.

Two lines into it, she stopped, realising what she had done. Her heart thudded. A fierce heat suffused her cheeks. She stopped washing and listened in embarrassed silence, straining to hear signs that would indicate whether the man had heard her. For a moment or two, she heard nothing. Then there was a gurgle of a mug picking up water, and a splash as it was poured over a body. Another minute, and she heard the door close.

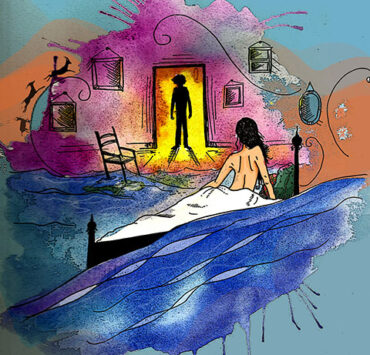

Megha couldn’t sleep that night. She felt as if she had intruded into somebody else’s privacy, almost as if she had actually peeked in when the man was bathing. But it had been totally involuntary. She was sure that the man would understand. He knew music, he would know how compelling the urge to sing could be. He wouldn’t misunderstand her, would he? She was a good, well-brought-up girl… he would know, wouldn’t he?

During the next few days, Megha washed her clothes much later. She couldn’t take the risk of singing again when the man was singing. She knew her urges too well. How she had suddenly burst into song in the middle of class, how she was scolded to sit still and eat because she sang between mouthfuls during lunchtime…

No risks.

About a week later, as Megha washed the clothes, she hummed to herself. Then, her voice took off on its own, and she sang a lively O. P. Nayyar song, with the chhup-chhup of the clothes in the bucket in rhythm with the jaunty, horse-carriage beats of the song. She was so involved in her singing that she didn’t hear the sounds from the neighbour’s bathroom, as he prepared to take a late bath. She was taken aback when suddenly, right in the middle of her song, the neighbour’s voice joined hers. But it seemed like it was the most natural thing in the world. To Megha’s horror, she did not stop singing. She could not stop. There was something intensely pleasing in the sound of her voice being in harmony with a deep, male voice. She couldn’t bring herself to stop making music, even though she was doing it with a man—a man who was not her husband.

She sang with abandon, but finally, her voice caught in her throat and overcome by her own boldness, she left the bathroom. She felt as though she had done something terrible. But technically, she had just been singing in her own bathroom, hadn’t she?

Various thoughts tumbled over one another in her head, and her heartbeat continued to pound in her ears. But in her mind, she could still hear the delicious sound of her singing with another person. The pleasure of a duet. The wonder of harmony. Megha had been singing ever since she had learned to speak. Yet, she had never once sung with a man. It was as if something large and significant had been missing in her life and she had never known it, until today.

The next day, Megha was back at nine, when the man usually took his bath. She surprised herself by making a lot of noise splashing the water around in the bucket, signalling that she was there. He started singing this time. A soulful Rafi-Lata duet. And she joined him, right on cue. Megha had rarely felt such pleasure. They sang in synchronous perfection.

It became a daily affair. Megha kept her date, every weekday. She stretched her time in the bathroom. She took to bathing after she washed the clothes. She starched clothes that didn’t need starching. She massaged herself with oil, rubbed her face with gram flour and scraped her heels—all activities that she had previously considered frivolous and hadn’t found much time for. The man stayed for longer too. Initially they sang just one song every day. As they became more familiar with each other’s repertoire, they became bolder, and stayed in their bathrooms for the duration of three, and occasionally four songs. Megha’s quick, flighty voice sounded strangely beautiful with the man’s steady, sombre one.

During all these sessions, they never exchanged a word.

Megha revelled in these singing sessions. They were the bright spots in her otherwise mundane day. She wondered whether she ought to tell Ashok about it, but she decided that she didn’t know him well enough to do so. Besides, he had no sense of music, and she knew he would probably not understand. Also, somehow, the fact that she had a secret animated her like nothing else could.

Her enjoyment showed. Ashok even remarked on her flushed face. She seemed so happy, singing all the time, smiling so much. For a while, he had been worried that she was lonely. But apparently, she seemed happy. He assumed that it was he who was making her happy, and that pleased him.

Megha saw her duet partner very rarely. Ashok and she passed him on the stairs a few times. But they never made eye contact for she always kept her gaze turned demurely towards the ground. She did not even know his name. It was rather strange that she knew every nuance of this man’s voice, and he, hers, and yet she did not know his name.

Sometimes, she suffered paroxysms of guilt. She wondered whether it was right to engage in what she considered an intimate act with another man. It frequently crossed her mind that both she and the neighbour were naked when they sang together. Separated by two walls, yes, but yet… Unbidden, an image of the man would flit through her mind—greying chest hair, a middle-age spread—and a hollowness would take root at the pit of her stomach when she realised that he could also be visualising her in the same way.

One day, Ashok decided to leave for office a little late. He took his time over the newspaper and the coffee. Her fingers fiddled with the hem of her kurta. Her big toes worried her toe-rings. She kept glancing at the clock, as the needle inched towards nine. She wanted to sing a Salil Choudhury number today. She needed to know if the man’s voice could navigate the turn and twists of the song.

Ashok wasn’t leaving.

She got irritated with Ashok for the first time in their marriage. She directed uncharacteristic vindictive thoughts towards him, and willed him to leave. But by the time Ashok finally left, it was nine-twenty. Megha rushed into the bathroom, but it was too late. The man had already left. She was extremely upset—and then she was even more upset because of how upset she was.

It didn’t seem right. It was not right to choose another man over her husband, whatever the reason might be. She told herself again that she was doing nothing wrong. But this time she wasn’t convinced. She cried all day, and was too tired to make lunch. She decided that this was it, the sessions had to stop. It was over.

That evening, Ashok was horrified to see his wife open the door with dark circles around her eyes. Megha clung to him, and cried even more. Ashok shook his head in disbelief. Just when he was thinking that she was well-settled and happy… she probably needed to go out more. He was a bad husband, he hadn’t noticed at all. Or perhaps she was homesick. He made a note to himself to plan a visit to her parents’ home.

He told her to freshen up, and that they would have dinner outside. Chinese. He knew she liked Chinese.

Megha slept fitfully that night, but was better in the morning. She smiled and shook her head when Ashok asked her if she needed him to take a day off. She hummed as she cooked breakfast. She was a new person. No more bathroom-singing sessions. It might be wonderful, but she couldn’t deal with the guilt. If Ashok was tone deaf, then so be it. He was still her husband and he was a good man and she wouldn’t look for anything else in any man.

Full of a righteous glow, Megha went about her work. She watched television and cleaned the house and organised the cupboards and did not miss her nine o’clock session at all.

A little after 10, as she was getting ready to wash the clothes, Megha heard a thudding and clanking noise on the stairway. She opened the door to see what it was. The stairs were filled with people, carrying articles of furniture downstairs. She watched for a while. Someone was moving house. She idly wondered who it was. Not that she knew anybody else in the complex, apart from, of course…

She froze as a gravelly, serious voice, a voice she knew so well, spoke instructions to the movers as they handled a steel almirah with a mirror. Megha looked at the man, and he looked back at her. For the first time, they made eye contact. He folded his palms in a namaste, and she did the same.

After she went back inside, Megha shut the door, and burst into tears.

Superb! But I must admit I wanted a “happily ever after” ending.

so beautifully written…loved it…even the ‘realistic’ ending

Thank you, Mira! :)

Thank you, Banashankari! :)

Lovely, Shruthi. Loved the unstated as much as the stated.

Wow, thanks, Sandhya

Absolutely wonderful.

Loved reading it so much. But why is your name spelled Shruthi here?

Sorry that question wasn’t for you. I accidentally posted it here. But read this wonderful piece too. So the words of appreciation remain for your piece.

Thank you, Sriti :)