When you watch John & Jane for the first time, you wonder whether it is a work of fiction or if the people and their stories are for real. The angst and aspirations of the central characters, their cynicism and hope, their weaknesses and strengths, are all so authentic that as an audience, you are bound to get attached with their lives and empathise with them.

The film is also high on technical brilliance, moving in and out of the different stories being told almost flawlessly; it scores high on the visual experience as well by creating an interesting mix of natural and artificial lights. But what stands out in this experimental film is that each character in the movie is a step ahead of the previous in living in a make-believe world, courtesy the call centres. You will notice the progression from hatred (Glen) to complete acceptance and transformation (Naomi), with each character essaying a different stage in that journey (Sydney, Osmond, Nikki, and Nicholas). The film is about a different kind of imperialism: a psychological one.

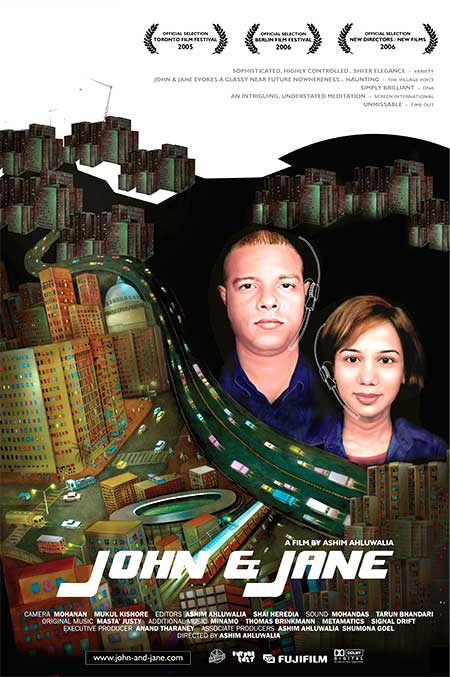

John & Jane film poster.

Call centres in India are an enigma, a phenomenon that a lot of people have tried to understand and failed to a large extent, but that never ceases to enchant people. A lot has been said about the economic effects of such call centres; the loss of jobs in the U.S., the cost reduction for international firms, globalisation, etc. John & Jane explores the inner turmoil of the people who work in those call centres, who take and make those long-distance calls, who give up their identities, their lives—some hope that they would get a new one, a better one, others just accept life as it is.

The film carries you as it moves along, charting the emotional highs and lows of the people in the film. You’re happy when you hear Sydney talk about dancing, and when he shows hope knowing that he can do better than to take calls in a call centre. With Osmond, you also start believing that his “I want to be a billionaire” dream is possible, even if not very probable. You feel proud when you hear his aggressive pitch as a private franchising agent. Nikki’s compassion is contagious, and through her willingness to help, she shows that she’s come to accept life and its terms, and you start to worry less for her. Glen’s cynicism is only matched by his ambition to be a model—for a Gucci or a Roberto Cavalli, no less! Nicholas’s efforts to keep his marriage as ‘normal’ as possible is very endearing, and you end up wishing that it only gets better for the couple. Naomi’s restlessness is palpable and you wonder, along with her, about what she wants in life. All seemingly normal people, who appear to have made a choice in their life, and want to stick it out—but only for as long as it takes to move on to a better life.

Ashim Ahluwalia tries to study the psychological intricacies of the average Indian who’s on the other end of the 1-800 calls being made to people half-way across the globe. They hope, while working in call centres, to be able to make the best of their lives. However, though they gain a few things such as financial independence and global exposure, ironically, what they lose out on is something much larger. They lose their peace of mind (under pressure to be pleasant irrespective of their own state of mind), they lose the opportunity to be with their family and friends (awake when they are sleeping and vice versa), and most importantly, they lose out on their individualism—their speech, their body language, their lifestyles, eating habits, moral values—everything that makes them, them.

Ahluwalia has been able to bring out this stark contrast very well—alarmingly so. Osmond (pseudonym for Oaref Irani) is shown to be having bacon and eggs for breakfast, something which is not very Indian. Nikki’s (Vandana Malwe, a Hindu) interest in evangelistic meetings could be out of her need to be able to relate with everything that is even remotely American. The most striking of them all, is Naomi (Namrata Parekh), who has even bleached her hair and skin to look blonde. Her statements like “I am totally naturally blonde” and “Blondes attract blondes” make you shudder at what these people are made to go through in their training and orientation sessions—it’s almost like planned systematic eradication of anything that is ethnic, physical or mental.

John & Jane provides viewers with a psychologically numbing experience. It gives the phrase “virtual reality” a whole new dimension. These 1-800 “answering machines” are conditioned to forget that they come from average Indian households and that they have a life different from the people they speak to on the phones. They get an opportunity to dream big, but that comes at a very steep cost. And Sydney sums it up when he says, “The only thing I think about is work. The only thing I do is work. The only people I meet is working people. The same people… and the same work to do.”

This film is absolutely incredible, completely blew my mind when I saw it. Seems more like a japanese or futuristic asian film – one of my favorite contemporary movies from India.