I want to start this article with a song; a song that stampeded its way through the country a few years ago. It was the hit ‘item number’ in the film Race: ‘Zara Zara’. Now before you crinkle up your eyebrows and wonder why any self-respecting writer would want to start an article with a song as ludicrous as ‘Zara Zara’, let me assure you that it is not my intention to write about its musical genius.

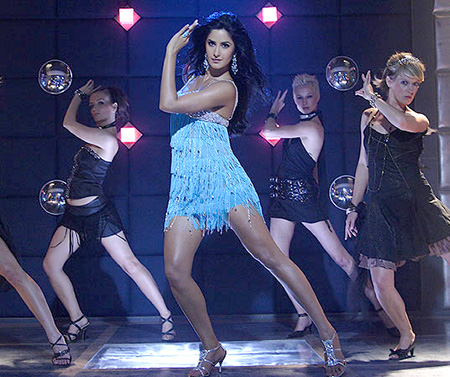

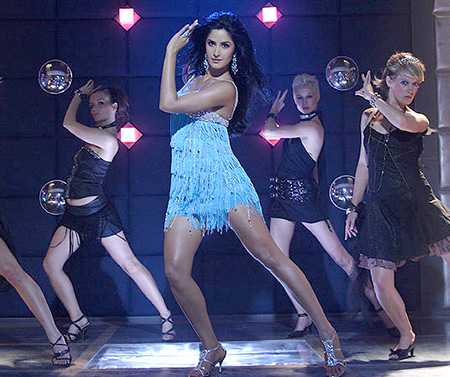

Instead, I want to talk about the lyrics of this song. While Katrina Kaif slithers and splutters on stage in a ludicrous attempt to seduce the incredibly horny and surprisingly guilt-ridden Saif Ali Khan, she sings—

Katrina Kaif might swivel her hips as sexily and suggestively as she wishes to, but the ideal notion of the woman hasn’t changed much. You can be sexy, you can even want sex, but the foreign-native dialectic continues.

“Tere hi tera hi intezaar hai

Mujhe to bas tujhse pyaar hai

Tera hi tera abb khumaar hai

Khud pe na mere ikhtiyaar hai”

This is immediately followed by—

“One time touch me like this

I like what you want

What you give, it’s a risk

Two time touch me like this

Three time touch me by far

Get over, here comes the crazy with me in my car”

There is a clear distinction that pops out when you actually read two different passages. While the Hindi lyrics talk about transcendental love and true love and other forms of incredibly ‘pure’ love (that is love not tainted by the vile tentacles of sexuality); the English lyrics, once you decode the ‘cool’ lingo, take on a distinctly sweaty, sex-ridden aspect.

Bollywood lyrics over the past decade, ever since the rise of the ‘Item Number’, have pushed the articulation of sexuality in English. ‘Zara Zara’ is not the only example we have of such musical split personalities. Take for instance the more recent 2010 film Hisss. The title track, which was on the top of Bollywood charts a few months back, has the following lyrics—

“Now when I find you, come wrap around you

Meri yeh saansein, yeh aankhein bulaye tujhe

My hips are shaking and the moves they are making

Meri yeh raahein, yeh baahein pukaare tujhe”

Alternatively, the song thrusts the reader into the world of platonic and incredibly creative metaphors in Hindi and into direct and rather rhetorical descriptions of wriggling hips in English.

Alternatively, the song thrusts the reader into the world of platonic and incredibly creative metaphors in Hindi and into direct and rather rhetorical descriptions of wriggling hips in English.

It would be wrong to say that all such expressions of sexuality are conducted in English; instead, what I am trying to point out is that the recent representation of female sexuality in Bollywood is slightly more complicated than it looks. The articulation of female sexuality in English is however not an unprecedented or sudden event. This ‘Zara Zara/Touch Me’ phenomenon comes from a long tradition in Bollywood of clearly associating the English language and the vague idea of the ‘foreign’ with sexuality and at the same time defining the ideal Indian woman with a sexless brand of platonic love.

Indian cinema, especially post-independence, has engaged in the creation of a certain brand of nationality which revolves around a vague and constantly evolving notion of ‘tradition’. Key to this idea of tradition is the relationship between a woman and her sexuality. Until the eighties, the sexually active woman was only seen fit to inhabit the seedy world of bars and night clubs. Adorned in bizarre outfits, this morally repugnant woman hung on to the baddies and performed dances that approximated sexual intercourse. This morally depraved and shockingly transgressive woman not only served to illuminate the ‘right path’ for a woman to follow, but also gave the voyeuristic audience the perverse delights that they disapproved and craved.

The chaste and pristine India was—and if certain right-wing politicians in India are to believed, still is—under attack by the Hydra-like multi-headed monster of a vague but lethal ‘foreign’ invasion. It is common knowledge that this project of westernisation was associated with decadence and immorality and signified by objects such as whiskey bottles, women speaking in fluent English, bikinis, foreign cars, etc. Post-globalisation, however, these foreign objects seemed less alien and the foreign condition became harder to define.

It seems that Bollywood has finally acknowledged the fact that women have their own sexualities, but they don’t seem to be very happy with it. The beginning of the 21st century saw films like Murder, Jism, and Khwahish exploit the exposure of the female body, turning the peeping tom pleasures of earlier Bollywood into a mass-produced cultural phenomena. Commentators often assume that the increasingly graphic representation of infamous ‘bedroom’ scenes implies some sort of liberation—I believe that it is simply an illusion. Katrina Kaif might swivel her hips as sexily and suggestively as she wishes to, but the ideal notion of the Indian woman hasn’t changed much. Sexuality is all well and good, but the overt articulation of it is still almost always in a foreign language. The Indian woman is still expected to walk on the path of chaste virtue, the only difference being that she is now assaulted by a different set of expectations (such as those pertaining to body image).

At this point, I would like to make an admission. I have been referring to Bollywood as a proper noun, referring to mainstream commercial Bollywood films, but I don’t want to fall into the trap of assuming that Bollywood is a single unified medium. There are many films and many voices, and obviously many representations of sex and sexuality. There are always exceptions, but it can’t be denied that sexuality is treacherous ground for Indian audiences.

Paperback copies of the illustrated Kamasutra are sold by book pirates in urban centres, while hand-holding teens are assaulted by right-wing thugs on Valentine’s Day. In such an ambiguous climate, the English-Hindi/Sex-Chaste binary comes as no surprise. Bollywood might have realised the commercial benefits of increasingly vivid ‘bedroom scenes’, but I do believe we are far from destroying the chaste-whorey binary once and for all.

I thought you were going somewhere with this article, and then, it sort of…died.

Impending deadline syndrome.

Gah. I wish it were the impending deadline syndrome. Honestly, I ran out of things to say. :S