Okay, so before I start, let’s get one thing out of the way. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen film was utter crap. Worse, even. If the crappiest film you can think of is crap, then this was the putridly foggy piece of shit that a dog with tummy ache leaves in the morning. Dorian Gray wasn’t required, and for the record, Naseerudin Shah was nothing like what writer Alan Moore envisioned Captain Nemo to be.

The League has similarities with Moore’s Watchmen; these ‘superheroes’ don’t have the mass cultural acceptability of Superman or Spiderman. He intentionally complicates their relationship to the Victorian society and their relationship with the reader. None of them are really heroes.

I did a creative writing course once, and my instructor used to go on and on about the value of a powerful introduction. I don’t know if the above paragraph would satisfy his especially genteel tastes, but it will have to do. I want to jump right into the middle of things. Let me say it: There is no one as bloody brilliant at writing comic books as Alan Moore.

Moore started writing in the late 1970s after a brief and extremely unsuccessful stab at selling psychedelic drugs. Later, he moved, doing freelance work for the British underground, and his obvious talent and incredibly unique style brought him to the notice of both Marvel U.K. and D.C. Comics. He introduced John Constantine, who would later star in his own series in Hellblazer, write The Killing Joke, which completely changed the Batman theme song and the general direction of the Batman saga, gave us V, the “Vaudevillian veteran, cast vicariously as both victim and villain” (I couldn’t resist that one!), he gave us the paranoid world of the Watchmen, and finally, he gave us The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

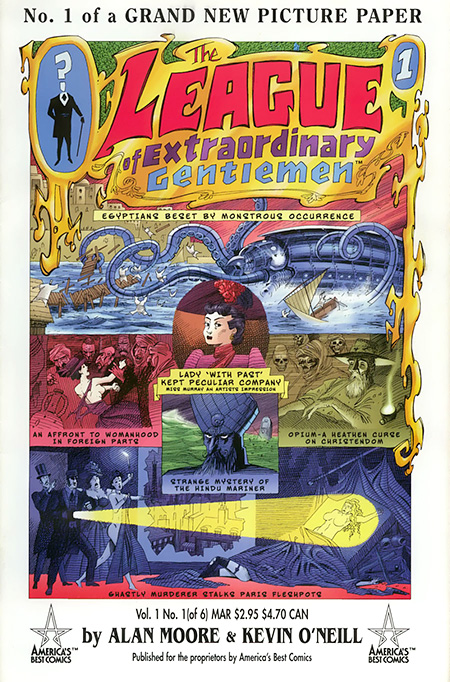

The comic book was first supposed to come out as a Justice League for Victorian England, and when he eventually published the first volume of the series, the reader was launched into a world of fictional anarchy. Mina Harker from Bram Stoker’s Dracula is recruited by a certain Campion Bond (later revealed to be the grandfather of James Bond) to create the league. She joins forces with Jules Verne’s anti-imperial scientific genius Captain Nemo to find Alan Quatermain, the protagonist of Sir H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines and, ironically, the epitome of colonisation. They are later joined by the first fictional detective, Edgar Alan Poe’s C. A. Dupin (from The Murders in the Rue Morgue). To this already amazing motley of the most fascinating characters in literature, add the titular characters of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and H. G. Wells’s The Invisible Man—even the great Sherlock Holmes and his brother Mycroft make appearances. The League decimates all boundaries of time and culture and gathers them together into an explosive, graphic, and absolutely anarchic narrative.

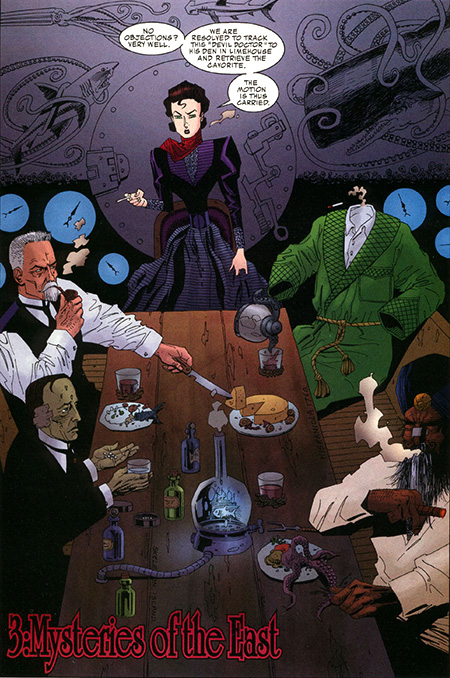

Kevin O’Neill’s artwork combines an extreme attention to detail with extreme physiological depictions. While each of the character’s dinners reflect an aspect of their character, Mina Harker’s waist is a bit extreme and has clear cyberpunk influences.

The plot line is pretty simple: These extraordinary gentlemen are gathered together by the extraordinary Mina Harker to help the great British Crown in its time of need. But these characters are handed out an additional dollop of complexity by Moore. Harker is dealing with the trauma of being ravaged by Count Dracula and the social stigma of being raped. Quatermain is dealing with an opium addiction and Nemo deals with the cultural alienation of having to work for and with the race that he spent most of his life hating. The beauty of the comic book is the almost infinite potential it provides—literary characters and references intertwine in this delightfully complex narrative.

In the first volume, these flawed, social freaks use their “super powers” to battle a mysterious Chinese adversary who threatens to blow up London using cutting-edge aeronautical technology. They then travel through East London’s docklands to Limehouse—incidentally, the same neighbourhood where the Victorian writer, Charles Dickens grew up and sang as a child in a local pub—to retrieve the stolen mineral called Cavorite which is essential for the race to the moon.

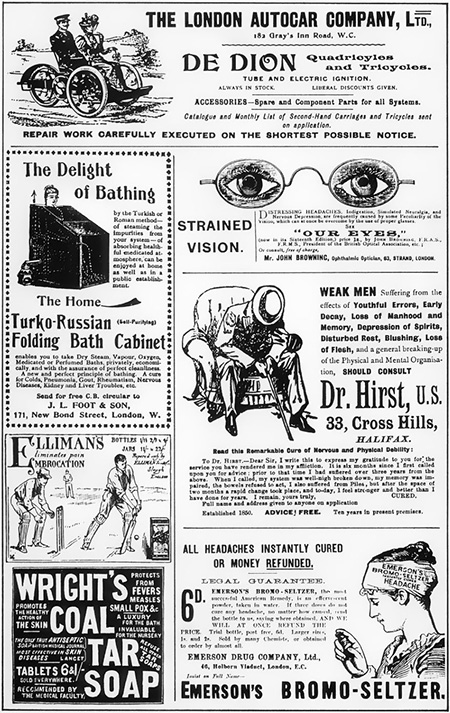

Alan Moore’s fascination with the cultural genre of steampunk is obvious throughout the series. Steampunk, which is a sub-genre of speculative and science fiction, came to prominence around the same time as the first issue of the League, and is literally the combination of science fiction and the Victorian world of steam power. (Films like Wild Wild West, Brasil, and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials novels are other examples.) What is brilliant about the comic books is not the simple replication of an ongoing trend, but the usage of Victorian in-jokes in combination with contemporary jibes. Take, for example, a half-finished bridge which would connect Britain and France, reflecting the problems faced while constructing Channel Tunnel. Equally entertaining are the various advertisements drawn by Kevin O’Neill, which, not surprisingly, are very well-researched and quite authentic.

The quaint and delightfully drawn ads are not necessarily works of fiction. For instance the ad for Emerson’s Bromo Seltzer is actually based on Issac E. Emerson’s bromide-based antacid and hangover cure.

Alan Moore set out to create a world of superheroes before the spandex-wearing, mask-donning avengers of justice were commonplace in cultural memories. These characters are designated social freaks and very flawed (more than one League member is also a serial rapist); they are not innately good, and they are definitely not heroes. Moore uses the comic book’s capacity for multiple modes of narrative. The story comes to us in pictures, newspaper clippings, minute visual details, and notes about the histories of each character; even the way the panels are designed tell us a little bit more about the story.

The captivating and addictive world (read these as literal warnings) of the League is one of Moore’s funniest and craziest works. You can expect graphic violence, vivid and bizarre sexual encounters, and gut-wrenching parodies. The grizzled, bead-wearing, and heavily bearded Moore probably had his tongue so far up his cheek that I am surprised he didn’t drill a hole here. The comic book is entertaining, intricate and with his subsequent volumes (Black Dossier and Century), the anarchic possibilities are expanded beyond belief. But The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Volume One is how it began.

Go read it; it’s bloody brilliant.

i woke up this morning, saw this article and decided to hate you. you had just robbed me of my next column idea.

“vaudevillian veteran, cast vicariously as both victim and villain”

thats not from alan moore. its by the guys who wrote the movie. and i think that was one of the major reasons alan moore dissociated himself from it afterwards..

Great balls of doo doo! You are right! I just checked.

@sol I am sorry to have robbed your literary cradle. I honestly didn’t intend to.