The idea that we can never really shake off where we come from is an overused and sometimes oversentimental one, particularly for people who don’t really feel like they “come from” anywhere for most of their lives. And they don’t care, because what one does is more important than where one comes from. Right?

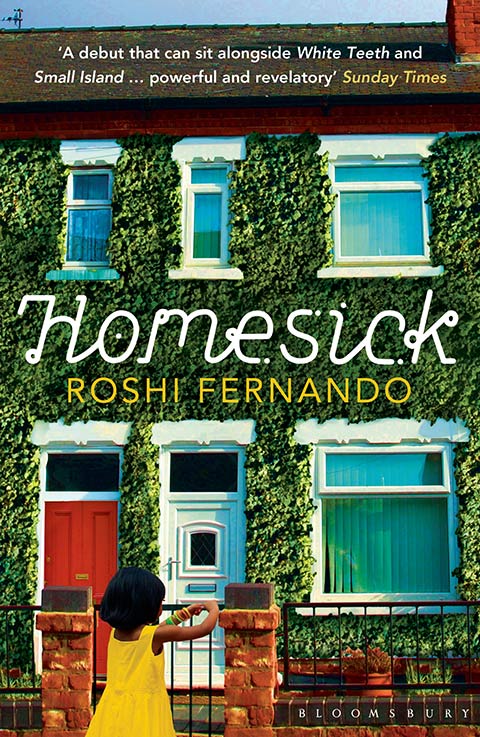

Homesick by Roshi Fernando

Homesick by Roshi FernandoEven so, it is hard not to connect with the wide range of emotions felt by the characters in Roshi Fernando’s debut novel Homesick. The author introduces Preethi, Rohan, Nil, Jenny, Dorothy, Victor, Kumar, Mumtaz, and Lolly: just a few of the members of an extended Sri Lankan family living in South London. From longing to disconnectedness to curiosity to fatigue, everyone in this family has a story to tell. Across generations, they are all acutely—and sometimes semi-consciously—aware of a home left behind, a life not fully lived.

The book is a series of fragmented memories. The story begins with a New Year’s Eve party in 1983, bringing together the whole family, and then moves into individual sketches of vaguely connected characters. The first-generation immigrants have a more conscious, sentimental place in themselves for Sri Lanka, as they struggle with racism, alienation, and sheer loneliness. The younger ones have more unsettling experiences, Sri Lanka making its way into their stories more subtly, more chillingly. The book, in a sense, belongs to them, and the way they live off their parents’ leftover consciousness of home.

The use of short stories in no particular order is a potent device, trapping the reader, compelling them to invest more than they can in each story, each incomplete life. Though many characters feature in each other’s stories, most of them live their lives without any significant contact with the others. From the orphaned gay divorcee, to the lonely archivist who finds solace in her dead lover’s son, to the ageing widow with fantasies of honeyed skin, to Preethi, whose experiences resonate throughout the book, the characters all show a sense of loneliness, of being lost, confused. It is not in their comparisons with England or even their words that Sri Lanka makes itself felt in this book. It is in the things that these children—for they remain, in a sense, children throughout the book—don’t or cannot do. There is a sense of there being something missing, even as they grow up, fall in love, make friends, get married, try new things. No matter where life takes the children of this tightly knit family, the one thing they all have in common is that Sri Lanka, willingly or not, proudly or not, is attached to their sense of identity.

The book ends during the war, when life finally forces Preethi back to Sri Lanka in one last desperate attempt to find what she has not yet found. She comes back with both more clarity and more confusion; more broken, but it is a somewhat peaceful kind of brokenness. More justified, less dissatisfying.

The author beautifully captures the guilt, homesickness, and also the subtle sense of community of this family, of a few representative experiences and slivers of life. We watch the characters narrate their stories, slowly, with great care and great longing, but with a hollowness that leaves us aching with fear and inertia and sadness. Each of them grows accustomed to loneliness, embraces it; their partners leave or die; they live on autopilot. They leave their families behind and move even further away from themselves. Every character ends up crumbling, fading slowly. Life is like that, perhaps: you live, vaguely; you do things that are ultimately inconsequential; you lose interest; and then you fade away. But perhaps we are reminded more strongly of how bleak life can be when we are away from home, constantly being reminded of a life we never bothered to live.

[Bloomsbury Publishing; ISBN 9789382951124]