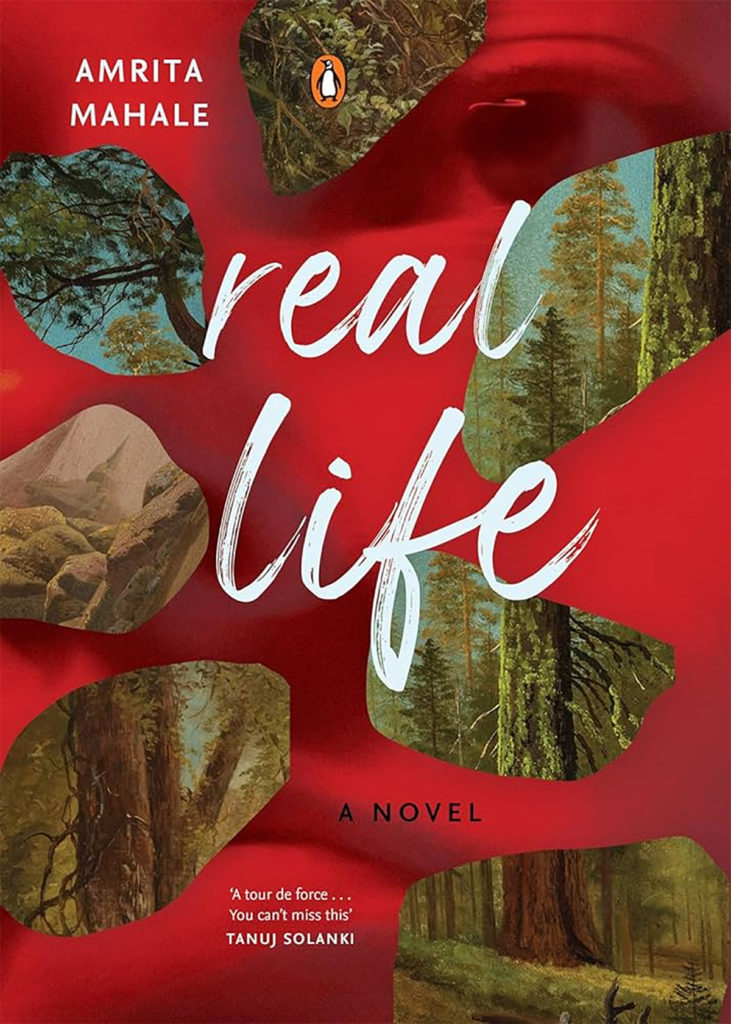

From its first line, Amrita Mahale’s Real Life hurls us into a mystery: the unexplained disappearance of Tara, a wildlife biologist. Mansi, her best friend, decides to retrace her footsteps, travelling to the remote Himalayan valley where Tara was last seen, deep into her field work. There, Mansi finds questions, memories, and stories of the prime suspect, a man called Bhaskar. As the mystery unfolds, Real Life takes us from Mansi’s grief-stricken perspective to Bhaskar’s, as he ruminates on the events that brought him into police custody, and to Tara herself.

A deft, compelling literary thriller, Real Life is about much more than a disappearance—it’s about making choices to live authentically, the push and pull we negotiate between our desires and society’s, and the way in which women’s stories are twisted and silenced. Outside of her life as a novelist, Amrita Mahale works at the intersection of technology and healthcare, which seems to inform how she approaches the relationships at the crux of this story.

Six years in the making, and the follow-up to her acclaimed debut Milk Teeth, Real Life is both engaging and memorable. We spoke with the author about the writing and research that went into Real Life, the political dimensions of female friendships, and what it means to live an authentic life.

I’d love to hear what writing Real Life was like for you, especially after Milk Teeth. This is a thriller—there are chapters end with cliffhangers, and we have changing points of view, from Mansi to Bhaskar to Tara. How did you approach the structure and the writing for this novel?

It took me six years to write [Real Life], but I wanted to make sure that it was very readable. It’s a heavier book than Milk Teeth, but I think it’s a page-turner, for sure.

I wrote Milk Teeth very non-linearly. I don’t think I started with the first chapter. I started in the middle, and I jumped back and forth, and there was a lot of restructuring that happened over the three or four drafts it took to get to the finish line. What’s interesting is that with Real Life, I started with the very first line. In fact, I wrote the first line—“Your head, they find it last”—I think a good three or four months before I even started writing the novel. And the first chapter has been in place since January 2019. So I started at the very beginning, and I wrote linearly. I think that was because this is three novellas, in some ways, and the voice is very different for all three. So the linear path to finishing this novel actually worked out well.

For the Mansi section, I started with the voice. Once I got into the voice, it was easy for me to just keep writing. I wanted the first section to have a bit of a soap opera flavour. She mentions soap operas in the first chapter, watching these ridiculous but addictive Hindi soaps—that was also what I was going for. I wanted to keep a fast pace and to end every chapter on a cliffhanger. All the emotions are dialled up a little bit. And then by the time I got to Tara’s section, which is the section I wrote last, I had to also make sure that I was in a calmer mental space. I had to intentionally relax my nervous system before I wrote her scenes.

I’d like to ask about the women in this novel, but before that, I think it’s fascinating how you write men in this book. In one of the sections, the reader views things from Bhaskar’s perspective, and something that really struck me is how, to him, everything that he is doing feels normal—he’s not able to see which of his actions or reactions is coming from power or privilege. It felt very real to me; the thinking is so ingrained. What was it like to put yourself in his headspace?

Bhaskar’s section was the hardest to write, even though, in many ways, not much happens. This was a headspace that was not very comfortable to occupy. I am an engineer by training, and I have worked in tech for a very long time, so I have been surrounded by Bhaskars my entire life—some of whom are actually good friends. So I have seen [things] from their eyes. Bhaskar is not a villain—I’m very clear [in the book] he’s not a villain—but he also triggers the events of the novel, and I didn’t want to excuse his behaviour at all. Some of the things that happened to him are very unfair. He is humiliated and rejected on multiple occasions, but instead of dealing with his own feelings, he directs his rage outwards, and he always directs it at the women in his orbit. And I think he’s also shaped by a world that teaches men that they are owed certain things—they are owed attention, they are owed affection, they are owed control. And when that doesn’t happen, many men turn bitter and vindictive, and that’s exactly what Bhaskar does. He’s a lonely man. He’s a wounded man. But in his case, this loneliness has curdled into obsession. So yeah, he is entitled. He is very self-justifying. There is a lack of self-awareness, but there’s also an internal world that I wanted to make sure feels consistent.

The podcast format gave me an opportunity to go into his head, and I think it also allowed me some level of separation. And I’ve asked myself why I chose the podcast format. I suppose [it was] because it’s Bhaskar directly speaking to the reader. And in a way, I suppose it was a writer in me putting my hands up and saying, hey, it’s not me, it’s him.

Over multiple drafts, I did try to be less judgmental of him; in his section, where my authorial voice comes in, I tried not to be too judgmental about him. But his actions speak for him louder than the author’s voice.

I think that was done so subtly—the way it’s clear he has been shaped to expect that the things he wants will happen to him.

I wonder how men will read this character, though. Some of my early [male] readers—friends who were comfortable sharing more candid feedback with me—did say they enjoyed his section the least, because they thought some of it felt a little stereotypical. But I heard the complete opposite from women. Again, this is just a few friends I’ve spoken to, but I’m very curious to see how the character of Bhaskar is received by men. Men who have been in the same spaces that Bhaskar has been—he’s very much a quintessential Indian engineer—but I also wonder how men who come from more creative backgrounds will see him, whether he strikes them as caricaturish or not.

The relationship that’s central to this novel is the friendship between Mansi and Tara, and they are both very clear at multiple times that this is a primary relationship in their life, which is so nice to read. What drew you to write that kind of relationship? Where did that friendship start for you?

Female friendship—I think it’s a gold mine for writers. Female friendships have intimacy, joy, there’s deep loyalty, but they’re also very intense; they can be intense and complicated, which is what makes them very interesting to writers. I’m far from the first to write about friendships.

Something that’s really funny is that the character of Mansi is named after my first best friend—I think I was four or five years old, and [she was] the first best friend that I remember. And we had such an intense friendship, even at that age. There was a time when we had a fight, and my family had gone to meet her family. She didn’t let me enter her house—she made me wait outside while my parents went in—which is just so ridiculous! I think some of that was also, you know, toddler dysregulation, it’s not [all representative of] female friendship, but it’s one of my earliest, very powerful memories, and that’s why this character is named Mansi.

So, yes, friendship is the emotional core of the novel, and Mansi and Tara are friends who are trying to hold on to each other while the world pulls them in very different directions. In the case of Tara, it’s her work that takes her away. In the case of Mansi, it’s marriage.

I think writing about female friendship is also a political choice. I work in maternal and child health, and my work involves looking at how women exercise agency, how they access information about health, how they make decisions about their own health. And as part of my work, I interact with women from very different backgrounds from mine, in both rural and urban settings. Something that really shocked me when I first saw it is that for a very large number of women in our country, marriage shrinks their social circle—it breaks all bonds they had before marriage, and it’s a way for families to exert control over women by discouraging them from having strong emotional relationships outside the family, even if it’s with other women. And I’ve seen that a woman who manages to hold on to her friends even after marriage is one who’s likely to be empowered in other ways too.

Friends, especially female friends, offer support in solidarity. They show you different ways of being in the world. They show you different ways of challenging patriarchy—and this plays out across classes. So I feel like my work with women deepened my belief that this is a serious topic. It’s not just fun, but it also has a political dimension.

“Friendship is the emotional core of the novel, and Mansi and Tara are friends who are trying to hold on to each other while the world pulls them in very different directions.”

Something else related to women and health in your book is this idea of women and illness: there’s a bit where Tara is thinking about her visual migraine and reflects on the history of women with illness: “From a young age, her eye was primed for mentions of illnesses in the biographies of famous women.”

Migraine is one of those things that disproportionately affect women—women are at a higher risk—and so it’s not been taken seriously medically, and also pain is super subjective. I just found that idea in the book so interesting, the history of women with illness. What drew you to that?

I’ve also had migraines for several years now—not as debilitating as Tara’s, but they turned into the visual migraines that I wrote about. It was just so fascinating to me—very uncomfortable, very painful, but also fascinating.

I’m so glad that in the last five or seven years, we’ve started talking about how the medical system doesn’t take women’s health issues seriously, and pain is often dismissed as just discomfort. So this was on my mind, and I remember reading Maria Popova’s Figuring, which is essentially snippets from the lives of different creative people from different parts of the world over centuries. There was a common thread: I noticed that a lot of the women who were able to devote themselves to art, or even to science, were not married. And what let them get away with not being married was that they were deemed “unmarriageable”, usually because of some illness. So they took something that was sheer bad luck—that you had this chronic disease, chronic illness, pain—and turned it into an opportunity to build a life for themselves that many other women of their times were not allowed. That idea was very interesting to me.

“I’m so glad that in the last five or seven years, we’ve started talking about how the medical system doesn’t take women’s health issues seriously, and pain is often dismissed as just discomfort.”

Let’s talk about structure. Mansi’s section is in the first person, but she is addressing Tara, while Bhaskar’s and Tara’s points of view are in the third person. How did you choose what worked for each section?

In the first section, I think I heard Mansi’s voice very clearly in my head, so I was just following the voice. It had to be in the first person. It had to feel very personal, very intimate. I wanted the reader to feel like they were in the mind of a grief-stricken person, with the understanding that grief distorts. So this is a slightly unreliable narrative. Even her memories are distorted by what she’s feeling right now, which is grief and guilt.

For the second section, it was very clear to me that I wanted to switch gears a little bit and go to the third person. And in Tara’s section, I did think about whether it should be the first or third person. [In that section] there’s a lot of writing about nature. And unlike Mansi, who pays a lot of attention to her surroundings—she has a voice that also describes the surroundings a lot—I think Tara, on some level, is also a scientist, so I feel like if I had spoken in her voice, it wouldn’t have felt right to write about nature the way I did. So [I wrote it in the third person], but I did move it to present tense, so it feels very different from Bhaskar’s section.

A running theme that I enjoyed in Real Life is the idea of parallel universes. They keep recurring, even in the epigraph to Tara’s section—“listen: there’s a hell / of a good universe next door; let’s go”, which is from one of my favourite E. E. Cummings poems. I found the idea of parallel universes—and how it links to the novel’s themes of agency and choice—to be such an interesting motif. I was wondering where it came from.

You know, when I started writing the novel, I really did not know how it would end. Tara’s section was a mystery, even to me. The first two sections played out exactly the way I wanted to. Of course, I figured [some of] it out as I went along, but for Tara’s section, I really did not know. I think I figured out how the book would end about three or four months before I finished the first round [of writing]. Then it was an epiphany, but there was a version in my head where, in Tara’s section, you slip into a parallel universe.

That’s so interesting. How did you rework it to fit?

It’s really interesting because you’ve seen what Mansi thinks of Tara, you’ve seen what Bhaskar thinks of Tara, and then moving to her point of view, in a way, is like moving to a parallel universe. Since you’ve made all these assumptions about who she is and where she is, but the reality is so different that it’s not very different from a parallel universe. And she had a parallel life that both of these people were not aware of at all, so she may as well have been in a parallel universe.

What does your writing life look like with a full-time job? And how did your work in tech impact how you talk about it in this novel? There’s a lot of really interesting thinking about technology that happens in the book.

I’ve worked in public health for over seven years now, and at the intersection of A.I. technology and public health—I lead product and innovation at a nonprofit. So for three years, when I first started writing this novel, I was in the A.I. for social impact space. Now it’s maternal and child health, but A.I. is a big part of what I do.

I’m a big proponent of taking a human-centred approach to designing technology. I feel like these ethical, more philosophical questions around, “how should tech be used for societal impact? How should A.I. be used for social good?”—these questions have been on my mind, and I suppose, because I work full-time, it’s very hard to keep work and writing really separate. The spaces where the two come together are really great for me. I think a lot about A.I., ethics, responsible A.I. Even when I’m at work, I’m very aware of the dangers of falling for technosolutionism. It’s very easy to do so. I think what’s on my mind during the work week then spills into my writing over the weekend, because that’s the only time when I get to do writing.

I did [scale] back at work for about a year, and that’s when I made the most progress on the book.

Are you part of a writing community? What does your writing world look like?

I don’t have a writing community whom I write with, but there is a community of writers I’m very connected to, and I’m very grateful for that, because we all have our ups and downs. I have this small community of writers who are also mothers. Shubhangi Swarup, Madhuri Vijay, Avni Doshi—our first books all came out a year or two apart, and we also had children around the same time that we started working on our second novels. So we have this little group where we exchange notes, ponder over motherhood and writing together. That’s been really great. I’m also friends with a lot of writers who are in Bombay, so we meet up from time to time. Again, there’s a lot of venting, there’s a lot of cheering on, reassuring each other that there are ebbs and flows.

It’s really great to have a community of writers, but I’m a very solitary writer, so I usually write in cafés away from home, just to create some space between myself and my home life. I’m very happy to write among strangers. There are people talking all around me, I’m hearing things around me that might make their way to the page, but it’s very hard for me to write around people I know.

This is related to the motherhood and writing idea: I was reading an interview recently [with Emily Adrian], where the author was talking about how she thinks of parenting and novel writing in similar ways, in that with both, it’s something that you’re raising, that’s asking really interesting and creative questions of you.

Absolutely. And I remember talking about this with some of my writer friends, and then what we realised was that they are very similar, but you can’t have your ego tied up in your child in the same way you can with a book. That would make you a terrible parent [laughs]. Your book is very much a reflection of you. The sooner you realise your child is not a reflection of you but their own person, the better it is for both [of you].

“It’s very hard for me to write around people I know.”

What kind of research was involved in writing Real Life?

I went to the mountains in 2018 when I was wrapping up Milk Teeth. I went to Kalga in Parvati Valley for a week. I was wrapping up the final draft, and that’s when it struck me that I really wanted to set my next novel—which was, then, just a germ of an idea, really—in the Himalayas. So I had that idea. I did not go back to the mountains for five or six years after that. Basically, most of the novel was written from memory, and from older pictures.

I wrote most of it in my apartment in Bombay, because I started writing the novel in 2019, and 2020 is when COVID struck. So for close to two years, especially because I had a young baby, it was impossible to travel. And then I finally went to the mountains in 2023 for two or three days, just a solo trip. And I was like, okay, fine. [laughs] I mean, I was very glad to be there, because that was when I started writing Tara’s section. But [I realised] my notes were actually pretty good. My research had held me in good stead.

I loved doing research for the novel, especially the part where I had to talk to a lot of wildlife biologists. It was a field of science I knew next to nothing about, so it was really, really fascinating. I also did a lot of reading about the Himalayas, the geography. It’s really funny, I had to do a lot of reading about the trees as well the vegetation, because Tara talks about what she sees at different times of the year at different altitudes. All of that is extensively researched. I know next to nothing. I know what a pine tree is, but I know nothing about the types of pine you’ll find references to in the book, because I have these detailed notes. And I have now forgotten everything.

Yeah, that’s okay. It’s in the book!

Exactly.

My last question: this is a book that’s so much about looking for a way of living that feels real and true—which is where the title comes from. I was wondering what authenticity means to you.

I feel like in some ways this is a question on everyone’s mind. It’s not just me, but I did think about that question even in Milk Teeth, in how Kartik views his life versus how Ira views her life. In some ways, I suppose Mansi is a lot like Kartik, and Tara in some ways is more like Ira—one of them is more caught up in other people’s expectations, [and the other is somewhat] not afraid, curious to the world, more open to possibilities.

I have thought a lot about this. What is ‘real’ life? Is it one that meets societal expectations? Is it one where you’re constantly performing, chasing accolades? A large part of my life has also been like that. I was good at math and science, so I ended up in engineering. I had a pretty successful tech career, but I decided to just step away and write my first novel. So I know that a ‘real’ life is something more private, more authentic, and more in line with what you see as important, even if it doesn’t make sense to others.