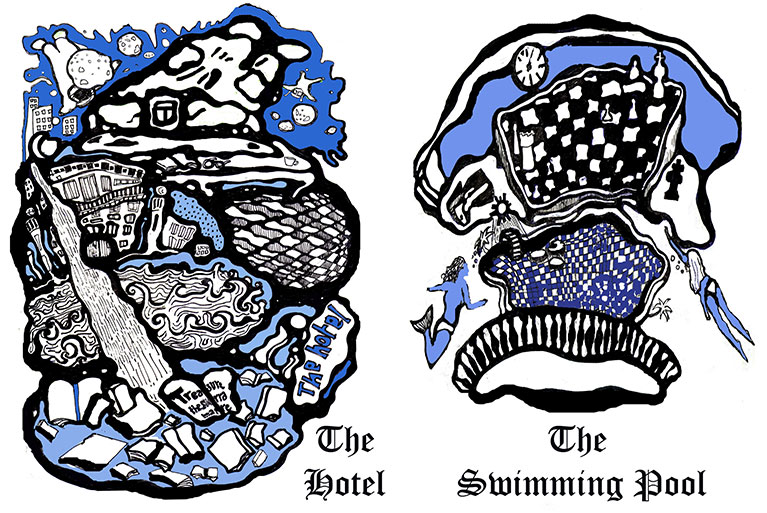

The Hotel

In the evening, he read by the light of dying astronauts. They fell, ablating in the atmosphere, artificial meteors illuminating the sky.

The abandoned beachfront hotel which had been Ravi’s home was slowly crumbling. The shoreline had flexed like a snake, the sea both receding and advancing, a fractal that concealed deeper, penumbral truths. The balcony where he sat every evening was buckling, a slow-motion dive into the sand dunes now encircling the hotel.

Already he had forgotten the precise sequence of events that had brought him here. Ravi had furnished the room with stacks of books retrieved with each salvage expedition. Now they criss-crossed the floor, an unsolvable hieroglyph.

Another flare of light lit up the sky above the beach, bathing the cover of the faded paperback of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre with lurid light. All around was the mad flexion of chronal tides. Ravi could feel their fierce stresses. Tonight it would be worse, he knew.

The Swimming Pool

The next day was flint hard and bright. From his room he could see the swimming pool below. The pool was slowly being drowned by the sand. There was still scummy water at one end, where something still living, moved, issuing ripples.

Ravi remembered coming here for swimming lessons as a boy. He remembered the chlorine stench, shivering under the shower after the warmth of the pool and the disinterest of the Y.M.C.A. instructor. Soviet engineers brought in to work on classified naval projects lived here with their families. Their children sometimes shared the pool during the lessons. He and the other boys had been awe-struck at the ease at which the foreigners navigated the water. The instructor had been moved enough to tell them that the Whites knew how to swim before they knew how to walk. While Ravi and the other boys paddled uncomfortably, the Russians had struck out effortlessly into the deep end. He remembered a blonde mermaid, crossing the pool with languorous strokes before slipping into unrememberable depths.

Now the tiles lay exposed to the sun, so blue-bright it hurt his eyes. He stepped back into the gloom. Sometimes the Professor stopped by for a game of chess. But he hadn’t been seen for days and the pieces silently stood on the board, contemplating long-lost victories.

He had found the chess set while rooting through storerooms in the abandoned hotel, searching for canned fruit. A cache of Royal Druk pineapple tins, found in the early days was now almost exhausted.

The set too was probably a survivor from the days of his boyhood. The older Russians used to conduct marathon chess tournaments amongst themselves. He had been particularly fascinated by the chess clocks, with their dials within the blocky plastic, the ‘flag’ whose fall indicated a forfeit. A loss due to lack of time. Zeitnot they called it. Now the silence between each move stretched towards eternity.

The Beach

Every afternoon, as he had done these past weeks, he left the hotel and walked on the beach. The walk had now become a ritual, a placatory rite.

The vast bulk of a beached submarine sprawled across the sand. The shadow of the black mass of the conning tower stretched towards his feet, the gnomon of an apocalyptic clock.

He walked by the shore, watching the deceptive calm of the surf. But he knew the shore plunged abruptly to the abyssal floor. Every Durga Puja, scores of devotees, mostly inebriated young men, waded in to immerse the idols. Not all of them returned.

Something glinted in the distance. It was a fallen cosmonaut. The shattered visor was garnished with glass. The frictive heat of ballistic re-entry had cremated the flesh within. The suit had survived, a cosmic urn. ‘C.C.C.P.’ in faint red still arced over the cyclopean stare of the helmet. He continued on his way. The water pushed at the suit, a small child cajoled to wave at relatives by her mother.

A fallen cosmonaut, a drowned submarine, the beach was a landscape saturated with symbols.

More artefacts emerged as he pushed on. A great bronze blade was visible, a single spar of a buried propeller. He had observed its emergence over the last few days, a dolmen presiding over the altar of the ruined beach. A white skull, doubtless a relic of one of the horses that had transported shrieking children across the sands had been placed at the base of the propeller, a votive offering to unknown gods.

The sands had seen many visitors over millennial cycles. The Romans had come once, guided by the light from the Buddhist viharas atop the hills, navigating by the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. The British had made a futile attempt to turn it into a ersatz Brighton. Then came the blue-collar workers and their families from the P.S.U.s and defence projects, and then the children of professors from the University. Right before the end, there had been the migrant workers from Orissa, construction workers in the enormous steel and zinc foundries that ringed the city.

A low roar filled the air. Every afternoon, a naval aviation Tupolev swung overhead, looking for survivors, or perhaps a reconnaissance mission, prelude to an attempt at retaking the Zone. It was a Tu-95, nicknamed the “Bear” by N.A.T.O.

The Bear roared overhead, the tepid air disturbed by the backwash of the contra-rotating turboprops. After a lazy loop it swung back. Evidently there was still Command & Control somewhere. A parasympathetic nervous system still clutching at limbs now long amputated.

That night he dreamt a dream of air, of being aboard the Bear, of flying across the Bay to the Andamans, a reverie of wave-washed concrete runways, quonset huts and military style omelettes.

The Dead City

It had rained in the night, giving the city a strangely leprous appearance.

Clouds roiled overhead, as if some unseen animal was writhing furiously. He walked alongside a row of bungalows with sunken gardens behind them. The streets had been fissured by repeated alchemical reversals of time.

The malls, multiplexes, software parks, pharma cities, special export zones, food courts had imploded in the tidal stresses of the chronal currents.

What had once been an approved retail environment had detonated into glass and dust. Only a long line of plush toys improbably remained intact, like teeth in a ruined jaw.

Now, or at least today, the city presented an aspect that dated back decades ago. Was it a coincidence that it was from the time of his own childhood? Or was the external landscape a mere psychic projection of his inner state? Projection or not, he moved with a certain surefootedness, heedless of the entropic chasms. Indeed, he was becoming increasingly convinced that his memory was the only thread that still sutured the city together. He could see a wall where someone had smeared three crude parallel lines. Stumps for a game of rubber ball cricket. The grease still looked fresh. Somewhere he knew, there would be a backwater nurtured by the chronal currents, a lagoon of forever.

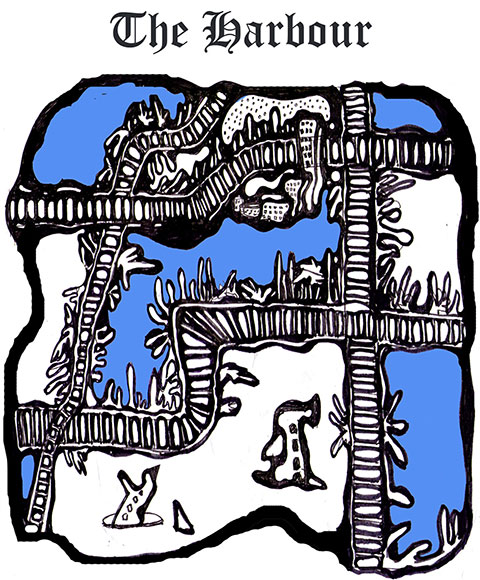

The Harbour

The harbour was criss-crossed with railway tracks. Iron, manganese, granite extracted from the hinterland, all to be exported from the dockyards.

Now the tracks were overgrown with vegetation. Some days he could still hear the mournful call of the locomotives, aural ghosts, acoustic spectres.

The harbour had been hit by waves of bombers during the Second World War when the Japanese had launched the famous Indian Ocean raid. Trace elements from that zone of violence began to appear. A crashed Japanese Aichi, nose crumpled by the impact lay at one end of the street. The huge red eye, the solar roundel painted on its body stared back.

It was not only the Japanese who had realized the city’s merits as a target. From the 1940s, atomic weapons had begun their migration from science-fiction magazines into reality.

He knew the city had featured high in the enemy’s targeting algorithms. Its similarities to Hiroshima were commented upon; both were port cities with naval dockyards. They were similarly ringed by hills which would contain and amplify the blast waves.

He knew the terminal language of a terminal landscape. The language of drag coefficients, overpressure waves, target-hardening, physics packages, hydrodynamic shock fronts and finally the hypocentre.

After all, the city had arisen over a defensive substrate of repressed aggressions – of victualling yards, submarine pens, listening stations, all enclosed by barbed wire—an architecture of absence.

Now he could see a row of cenotaphs, risen from what had once been the Dutch town. Long hidden funerary landscapes were emerging into the uncertain light.

The necropolis was a reflection in the mirror of Time, of the dead city it would become under nuclear skies.

The Hotel (II)

Dusk had seeped into the world. The walk had been long and tiring. No more pineapples, he thought. Soon the sky above the beach would turn into a movie screen. A screen projecting the same film every night, the disintegration of the asteroid, the unmaking of the space elevator, the fall of the astronauts.

A brown cardboard file lay on the table near the chess set. “Time is escaping from the universe,” the Professor had said in what had been one of their last meetings. “Read the Senovilla paper,” he had urged, leaving behind the file.

Senovilla had sought to explain the apparent discrepancy between the size of the universe and the time it took for light to reach Earth from the farthest astronomical objects. His conclusion had been implacable. The discrepancy had not been because of the expansion of the universe powered by dark energy, but was due to the depletion of Time herself, an optical illusion spanning the island universe. Escher was right, thought Ravi.

The rotating beam of the lighthouse poured through the windows, For a moment, he saw himself in the mirror, a face hollowed out by malnutrition, speckled with sand and salt, glittering points of madness in the eyes. Then the beam swept on, the dial of a giant clock. Phantom light, he knew from the long-collapsed lighthouse.

Ravi walked to the balcony, the vista stretching over vermilion sands. Far down the coast was the great space elevator, golden strands of spun carbon nanofibre reaching into Near-Earth Orbit.

He was navigating a science-fictional topoi. In the skies above the sand dunes, the accelerating rate of change had finally reached its logical conclusion.

Orbital space had become an intense zone of activity, infused by Venture Capital, crowded with asteroids captured for their metal, zero-g holiday resorts for H.N.I.s. There was also the inevitable layer of stealthy defence projects, particle weapons, early warning satellites, surveillance cameras, a layer of militarised space.

It was in this zone that the research station had been established, in an asteroid captured and hollowed out by a billionaire undergoing a mid-life crisis.

He had vague memories of the cavernous central sphere within the asteroid but was no longer able to distinguish between his own memories and those purveyed by the military-entertainment complex. Were these memories really his own? Or were they the residue of a cunningly crafted reality T.V. show?

He knew the experiments were connected with an artificial singularity—a test-tube baby black hole. They had attempted to recreate the final moments of a dying star. The glyptic symbols of the data transmission from the asteroid still evoked phosphorescent echoes in his mind. Ravi knew that his memory had been irretrievably green-screened, saturated with C.G.I. visions. Had he actually worked on the project?

Right before the end, reality had become a bad sci-fi movie, the kind you watch at four in the morning, unable to sleep, unable to turn the T.V. off.

The Beach (II)

During the night the winds had peeled away layers of sand. Now as he walked, he could see low humped shapes below the sand, concrete tumuli.

The Professor had told him that these were bunkers built by the British during the war who had feared the arrival of a Japanese invasion fleet.

The winds were methodically exhuming the beach. The sands were slowly revealing an entire defensive landscape, a continuous topography of fortification, of pill-boxes, subterranean command centres, gun emplacements, and coastal batteries.

Ravi knew that it would soon be impossible to walk on the beach. The flow of time was headed towards a cataract. Already it was growing dark. Like the sea, the hotel was now part of a past that had long since receded.

He decided to sleep on the beach, his back against the wall of one of the bunkers, under a sky untenanted by stars. The Moon was a cadaver awaiting dissection on the table of the night.

The Hypocentre

That night he dreamt of the Hypocentre, the ground directly beneath the nuclear airburst. The fireball would expand in microseconds, X-Rays superheating the air to temperatures well above that of the surface of the sun. Buoyant, the fireball would rise above a cacotopic landscape, a dark star in an irradiated firmament. Then would come the hydrodynamic shock front, a Machstem that would obliterate the city in an enormous outflinging radius, flattening structures, reducing the streetscapes into incoherence. The atomic heart needed to beat just once. He dreamt of the clocks of Hiroshima forever frozen at the moment of detonation.

The Submarine Pens

The Submarine Pens were located deep within the naval yards. They were connected to the harbour through a hidden inlet channel. Their womb-like architecture, subterranean and yet connected to the ocean meant it was a zone rich with promise.

Ravi walked amidst the colossal reinforced concrete structures. He remembered a school excursion to Dholavira, the Harappan city in the Kutch. The Pens reminded him of the Great Bath, inhuman in its mathematical perfection.

He had read somewhere that Hitler’s Atlantikwall defences built on the coasts of Europe would be humanity’s longest lived artefacts, outlasting even the Pyramids.

Similarly, these colossal megaliths of the Plutonium Age would survive even as the rest of the city underwent a “vapourization event”.

At detonation, the Pens would become the anvil of creation. The chaotic flow of enormous energies liberated at nuclear Ground Zero would ensure that the sky above the Pens would seethe with a vast constellation of exotropic particles born and then annihilated, all within picoseconds.

He stumbled over an anechoic tile. The submarines were gone but the tiles which had once scaled their metal skins were everywhere, atomic serpents shedding their skin. He thought of Adi-Sesha, the World Serpent whose coiling and uncoilings advanced and negated time respectively, a clock the size of the universe.

A faint tang of engine oil still hung in the air, amidst the drifting motes of dust. The water lapped at his feet. The Pens were colossal, a rectangular inland sea pillared by shafts of light.

In the moist gloom, it was hard to make out their extent. He wondered about the far shore. Was the blonde mermaid there somewhere, waiting? Ravi stepped into the water. Currents played beneath his feet, pulling him. He kicked out, confident of a shore awaiting him.

(This story originally appeared in the August 2013 issue of The Four Quarters Magazine.)