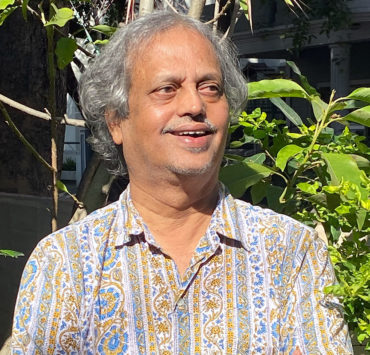

At 62, Shivaswamy hopes to live a happily retired life. He’s even taken the steps to get there—purchasing a three-bedroom apartment for himself and his wife in Bengaluru, in a soon-to-be-constructed building. However, everything changes when the builders demand the full payment well before the flats are constructed. Shivaswamy finds himself forced back into a workforce that seems reluctant to have him there, in a fast-moving city intent on leaving him behind.

What’s Your Price, Mr Shivaswamy?, written in Kannada and translated into English by M. R. Dattathri, is about a man caught between his ideals and a hungry, capitalistic world. It’s a novel that invites readers to sit with uncertainty. In the midst of this uncertainty, though, there is friendship, philosophy, and a sharp portrait of modern Bengaluru.

We spoke with the author about the experiences that led him to write this book and the challenges of self-translation.

What was the seed of this novel? What was your very first idea for this book, and did that change at all in the process of writing?

I am a character-driven storyteller. For me, it is always the characters who appear first, before any other element of a story. Usually, it is the protagonist who arrives unannounced, lingers in my mind for days, brings along family and friends, and [this] eventually grows into a novel. That is why, for me, the birth of a novel remains, in many ways, a mystery. I suspect it is the same for many writers.

For this novel, the seed arrived in the most ordinary of settings: a job interview. I recall an incident from my time as head of the Bengaluru branch of a multinational software firm. My role involved meeting and assessing candidates after they had cleared the technical rounds. One afternoon, a gentleman walked into my office. He was well past 60. The position was not really meant for someone so senior, and it required continuous travel to client sites. He was willing. If selected, he would have to report to a manager almost half his age. He was willing to accept that too.

As the interview progressed, I asked, “What made you start looking for a job after retirement?” It was not idle curiosity; it was an important factor in my decision. He paused for a moment and then replied, “Due to certain hardships that have befallen my family, and some poor financial decisions I made, I have lost my retirement savings. That is why I need to return to work.”

His words were heavy with sorrow, his face clouded with worry. That expression stayed with me long after the interview ended. He did not join my company, and in fact, that was the only time I ever met him. All I knew about him was the brief reply he had given to my question. Yet even today, when I picture Shivaswamy, the protagonist of this novel, I see his face. Everything else in the story is entirely fictional, but that brief encounter became the seed from which the novel grew.

When a character lodges in my mind in such a way, it follows me day and night, urging me to weave its story. The backdrop usually emerges from my own experiences, things I have lived through, read about, or heard from others. As the story develops, the original incident that inspired it sometimes changes so much that even I can barely recognise it. A grown tree seldom resembles the seed from which it has sprung. The same is true of a story and its origins.

I’d love to hear more about how the friendship at the heart of the novel (between Dhaval and Shivaswamy) came to you. They have so much in common, and yet, their interactions often highlight the ways in which they differ. How did you approach writing this friendship? What was important for you to highlight in their interactions?

The friendship between Shivaswamy and Dhaval emerged as a crucial literary device for me. They are not the kind of characters who can easily reveal their inner lives. Age and upbringing often create a certain reserve, a reluctance to share one’s private thoughts. With contemporaries, conversations open up more freely, sometimes even reaching the level of soul talk. Between Shivaswamy and Dhaval, that openness is not natural; it had to be carefully shaped. Their patience-tested friendship created a space for this to happen, allowing me to explore a multitude of themes and ideas through their interactions.

Yet this friendship is not free of self-interest. Shivaswamy accepts it, almost reluctantly, as a means to survive the situation he finds himself trapped in. The trouble he has run into while buying a house, unexpectedly and innocently, now threatens to sink his retirement funds and has left him in a financial predicament. To recover, he needs a job. To keep that job, he must learn to manage relationships. His friendship with Dhaval becomes one such necessity. Over time, however, he begins to value it in ways he had not expected.

For Dhaval, the friendship fills an emotional void. His only close friend, Preetam Jain, has passed away, leaving a void that no one else could fill. His wife is no more, and his son and daughter-in-law have abandoned him. Though he is the owner of a large company and surrounded by professional acquaintances, he is starved of genuine connection. In this sense, Shivaswamy’s arrival feels like an accidental yet inevitable way of bridging that gap.

Still, writing this bond was not simple for me. There is a vast social and economic gap between them, and their personal lives are fundamentally different. What holds the friendship together, especially in its early stages, is Shivaswamy’s patience. Over time, once they both discover the comfort that arises from their conversations, the relationship grows stronger. They begin to seek each other out. After a certain point, the hesitation drops away, and their exchanges become genuine and unguarded.

As a storyteller, that was the moment of joy for me. The novel became easier to write when I reached that stage, because in their dialogues I could narrate not only their stories but also reflect the deeper struggles of the world they inhabit.

One of the threads that weaves through the novel is this reflection on what it means to be a certain age in a quickly developing city, where certain things are required for survival. This, and what it means to be of a certain age in the workforce: both in being forced to work past retirement age, and the complications or confusions that unfold being a newcomer in an office where most people seem to value youth. What drew you to focus on this theme?

Thank you for this thoughtful question. The reflection on age is one of the central themes of this novel, and there is indeed little difference between its fictional world and the lived reality of today’s Bengaluru. This theme emerged from my own observations and experiences. Modern professions, particularly those in the I.T. sector, have created immense opportunities, but they have also deepened an age-based divide. While this divide exists everywhere in the world, it feels acute especially in India.

“There are countless Shivaswamys across cities like Bengaluru, unable to fit in, yet unable to walk away.”

During my years in the U.S., I worked alongside colleagues who were well past 50 and still enjoyed coding with youthful enthusiasm. That was not considered abnormal there. But in the I.T. industry in India, such a presence is rarely accepted with ease.

Bengaluru, being the I.T. capital of India, bears the brunt of this age mismatch. The average age of an I.T. engineer in Bengaluru is reported to be around 29 years. A survey also noted that a mere 1.2% of total employees in an I.T. company are over 50. The first generation that rode the wave of economic liberalisation in the 1990s and built India’s I.T. revolution has now crossed 50. Where have they gone? Most companies gently or firmly nudge them into retirement. Others withdraw on their own, unable to keep pace with the relentless speed and pressures of the new jobs.

This is where my protagonist, Shivaswamy, belongs. He represents employees who, out of necessity, continue working beyond 60 and encounter peculiar and disheartening challenges. Imagine an entire company behaving like a group of 25-year-olds. For an older employee, the experience can be isolating, even alienating.

This phenomenon, however, is not confined to the corporate office; it permeates the city itself. Increasingly, our cities seem designed for the young. It is said that approximately four million jobs in Bengaluru are directly or indirectly dependent on the I.T. sector. When such a large share of a city’s population revolves around a single industrial ecosystem, the consequences are dramatic. Pubs overflow every evening, T.G.I.F. parties dominate Fridays, I.T. money flows like a river, and with it come traffic jams of impossible proportions and skyrocketing real estate. The morning metro is crowded with young faces.

This is the Bengaluru of today, and it is the backdrop against which Shivaswamy struggles. His anguish is not just his own. There are countless Shivaswamys across cities like Bengaluru, unable to fit in, yet unable to walk away.

In the acknowledgments of this book, you write that translation is a lot more difficult than writing a novel. I’m very curious about the level of effort self-translation requires. How does the novel feel to you in Kannada versus in English?

Yes, translation, particularly self-translation, is more difficult than writing a new story, and there are several reasons for that. First and foremost is the gap between the social language of the characters and the language of the writing itself. My social language is Kannada. Like most Indians, I use English for my work and for engaging with the world beyond my language. I grew up in Chikkamagaluru, a small town where everyday life unfolded entirely in Kannada. The characters I create come from the social environment I know intimately, so their natural language of expression is also Kannada.

When writing fiction, the social language of characters becomes inseparable from the story. When characters speak to themselves, quarrel, laugh, curse, or fall in love, each emotion carries the texture of their social tongue. That texture holds immense value in literature. When the language of writing is separated from the social language, the story loses its original flavour.

The breadth and flavour that Indian languages carry, with their regional diversity and deep cultural roots, is difficult—sometimes even impossible—to reproduce in Indian English. This is because English is not a social language across all levels of Indian society. Outside metropolitan cities, it is not even a link language in much of the country. As a result, English lacks the layered social registers that our Indian languages possess. Take Kannada, for example. A policeman, a temple priest, a blacksmith, and a politician would all sound very different in their speech. Their choice of words, cultural expressions, and the social cues they convey vary widely. This variety exists because Kannada is a lived, social reality across all levels of society here. When we bring such characters into English, these differences flatten out and lose their flavour.

And Kannada itself is not a single entity. There is the Kannada of Mysuru, the coastal Kannada, the Malenadu Kannada of the Western Ghats that I use most often, and the Dharwad dialect of North Karnataka. The richness of these variations adds nuance and depth to the portrayal of characters. These subtleties are almost impossible to preserve in English. Deepa Bhasthi, a brilliant translator, discusses this insightfully in her essay Against Italics, appended to her Booker Prize-winning translation Heart Lamp. A story depends on language far more than we tend to assume, and this truth becomes stark only when one attempts translation.

“A policeman, a temple priest, a blacksmith, and a politician would all sound very different in their speech. This variety exists because Kannada is a lived, social reality across all levels of society here. When we bring such characters into English, these differences flatten out and lose their flavour.”

For a writer who also becomes the translator, another problem arises: the lack of thrill in discovery. The plot is fixed, and the end is known. How does a storyteller like myself stay motivated to continue the work? You are not watching a live match; you are watching a replay, and the result is already known. That is precisely the challenge when the writer himself becomes the translator of his work.

Then there is the matter of over-scrutiny. This is the most brutal challenge. Jhumpa Lahiri points this out in her book Translating Myself and Others, and I have experienced it as well. When you examine your own work too deeply, it begins to unravel. The original can collapse under the pressure of such intense re-reading. You begin to doubt the very impulses that gave birth to the work. Fiction, whether your own or another’s, is not meant to be read 10 times over. You may end up demolishing what you once built and reconstructing it, which is often more painful than writing something new. And there is never a certainty that what is rebuilt will surpass what once stood.

What kind of co-creation happens in translation?

Self-translation has its gifts. The most important one is the complete creative freedom it allows. For me, translating this novel was almost like creating a “second draft” written for a new audience. I allowed myself to tweak it quite liberally. And thankfully, I did not have to seek anyone’s permission to do so. It saves both time and creative energy.

Even more significant is the ability to accurately capture the voice of the characters. When we talk about translation, language naturally takes centre stage, and rightly so. But that’s not all. Especially in fiction, it is crucial to understand the inner world of the characters, their design, to grasp their voices, and to use language that aligns with their psychology. Who else can truly comprehend and understand these characters better than the one who created them?

Self-translation, then, is both liberating and exhausting, like climbing the same mountain by a different path. It demands patience, but it also offers the rare joy of seeing your work reborn for a new set of readers. That is worth the climb.

“Fiction, whether your own or another’s, is not meant to be read 10 times over.”

How do you feel like the English version differs from the Kannada version, in terms of its audience?

When it comes to the audience, I do not see a significant difference. Today, many readers are bilingual, and their expectations are broadly similar.

Therefore, more than a linguistic divide, my novel has resonated most with readers whose life experiences are close to those of my characters. This novel has already been translated into Telugu, and the opinions of Kannada, Telugu, and English readers have been strikingly similar.

A central conflict for Shivaswamy is the idea of jumping “from one boat to another”, committing entirely to the path of renunciation without doubt. Shivaswamy exists in this confusion in-between the two boats. The novel offers no easy answers, and highlights several grey areas. How did you know where the book had to end?

Just as a piece of music gently descends and comes to rest in silence, so too does a novel find its ending. It is something one senses inwardly, something that can be felt through the inner ear and seen with the inner eye. Beyond that point, the story simply cannot go on.

The recurring image of Shivaswamy’s dream, in which he is caught between two boats, is the central metaphor that runs throughout the novel. He cannot remain secure in the boat he stands on, nor can he summon the resolve to leap wholeheartedly into the other. His courage is always lacking. In the novel, his guru Kereswamy has a key line: ‘Only those with unwavering faith in reaching another boat should dive into the waters.’ Shivaswamy never gains that courage.

The novel’s ending had to reflect this theme. There was no question of providing a different kind of conclusion, one that would force a final decision upon Shivaswamy. Any such resolution would have felt unnatural and would have run contrary to the novel’s natural flow and the character’s psychology. Shivaswamy’s character is built and shaped on this very indecisiveness.

Since the character’s decision is left to the reader’s imagination, the ending becomes, in a way, a moral test for the reader. When a reader is entrusted with the ending of a story, they enter it more intimately, carrying it within themselves.