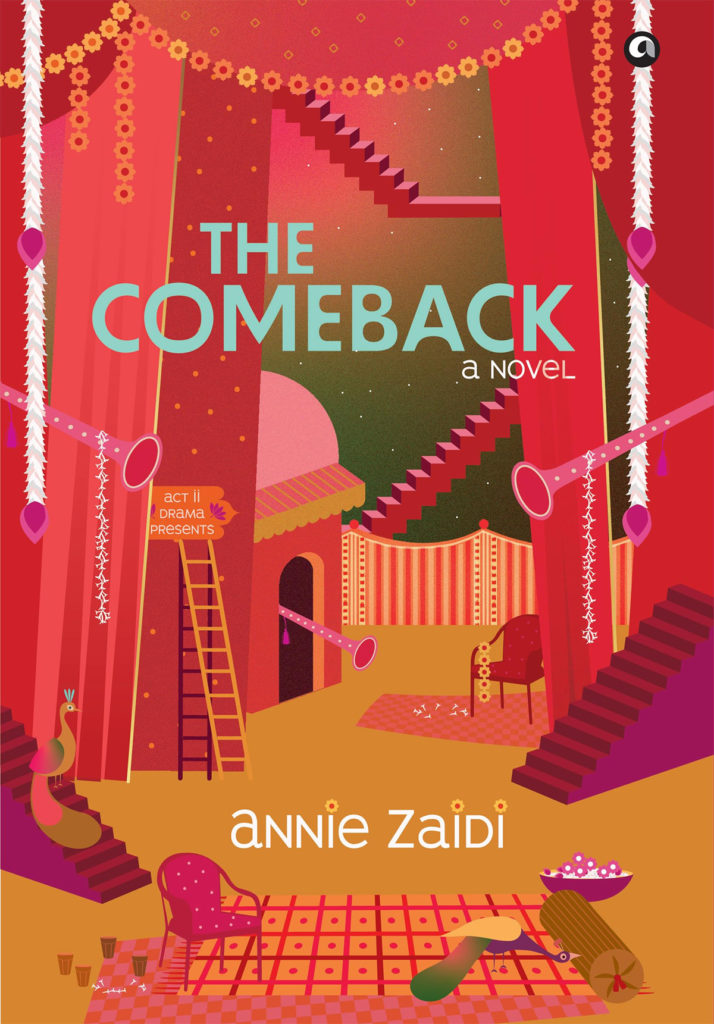

Annie Zaidi’s writing—in her poetry, plays, nonfiction, and fiction alike—has always engaged thoughtfully with the complicated reality of what it really means to be a person in contemporary India. In her latest novel, The Comeback, Zaidi turns her attention to a space that’s long captured her attention: the stage.

In The Comeback, we meet actor John K. (born Jaun Kazim), who in a fateful interview speaks without thinking and accidentally reveals information that ruins his college friend’s life. Asghar, the friend, finds himself unemployed and disgraced, and back in his and John’s hometown, Baansa. He refuses to speak to John, who himself is in a bit of a slump with his artistic career.

From afar, and through John’s eyes and ears, we learn that Asghar has started a theatre company, which becomes successful beyond both their wildest beliefs. Over a hundred-and-eighty pages, we follow John on a journey away from artifice and towards reconciliation, second chances, and a rediscovery of his artistic calling.

We spoke with Annie Zaidi about her love for theatre and playwriting, where The Comeback came from, and the trust and solidarity that the arts require.

The first thing that struck me when reading The Comeback is that it feels like it takes place at a distance from where the quote unquote “action” is. I found that such an interesting choice, where we’re hearing about things from a distance, and we’re not on the stage itself. What made you want to set it at that distance?

That’s interesting you pick up on that. It was not done consciously, but I think one of the reasons I wrote the book at all was that I felt like I was at a distance from everything. I was missing theatre. I wasn’t writing theatre anymore, I wasn’t even watching too much professional theatre. It came out of my own sense of feeling like I was missing out on something and wanting to be at the centre of things, but at the same time, being in a smaller place and recognising that being at the centre of things doesn’t necessarily mean being in a big city. Sometimes you can be in a big city and still have serious F.O.M.O. because all the cool things are happening somewhere else, you know?

Also, a little bit consciously, I was thinking about our commitments to big cities in the arts. I think it’s unconscious and we can’t always control it, because we go where the money is, and we go where the big industries are. Writers tend to congregate around places where the publishing hub is, [actors] to where the film scene is. But at the same time, I think that we also are then controlled by the big scene. It’s a trade-off, and we trade our own sensibility. The other possibility that is traded in is of actually having control over what you want to do, setting up your own thing in your own social context. So I think it comes a little bit from there, the sense of wanting and not wanting to be in the thick of things.

You note this in the book’s acknowledgments, the importance of art taking place outside of the big cities, but I think your book also talks about how art spaces like Asghar’s don’t need validation from the big cities. I was wondering if you want to talk about that, but also generally what your experience has been with theatre in smaller cities.

I grew up without any theatre whatsoever, because I lived in such a small place and there was no theatre there. Except for what we did ourselves in school, and college theatre, there was nothing. If we didn’t do it then it just didn’t exist. So in a way, what I have written is a fantasy—it’s not based on any reality that I know of. But I think even the fantasy must exist. We must have our fantasy and we must imagine that it’s possible before it becomes possible.

In India, I know that people have their own small artistic scenes. But making a living from theatre in small-town India, I have not seen yet. I don’t know how it might become possible, but in writing [this book], I was presenting a model for how it might possibly become viable. It cannot happen, say, in a very small town, but a town that has a university, is big enough to actually have tens of thousands of people for a potential audience, where you have bureaucrats and you have some kind of, for the lack of a better word, what we call ‘intelligentsia’.

“We must have our fantasy and we must imagine that it’s possible before it becomes possible.”

In my imagination, I think that if you did something super cool in a small town at least once or twice a year, there’s no reason why you can’t build that audience. In the West, you do see it happening. In England, for example, every small town has its own local theatre. It does put on shows. Whatever kind of living people make, maybe they have small jobs on the side, whatever they do, but there are people who run theatre groups in small towns as well, so there’s no reason why we should not also have that in India. Unlike books [and literature festivals], where you can just fly in, theatre requires year-round practice, and it is a slightly more expensive proposition—which is why the rigour of it is important, which is why the local group is important, because you can’t just suddenly expect that overnight, a super-talented group will spring up.

I’d love to hear about how you chose to write from the perspective of Jaun. I found him such an interesting mind to inhabit, because occasionally he seemed so incapable of seeing what he was doing or how it was affecting people, but you really couldn’t help but root for him. What was it like to build that perspective?

I decided from the outset to write from his perspective partly because he’s the one that’s done this horrible thing. If I wrote it from Asghar’s perspective, it would be a very angry book. There was also the danger that, in Asghar’s voice, anything that he pulls off and accomplishes then becomes a self-aggrandising project. If he starts talking like, I went here and I did this and I made this happen, you would hate him, right? But from Jaun’s perspective… Firstly, he’s a very unhappy man for all his success. Whatever success he’s won, he’s won it very hard. I think we root for him not just because he’s flawed, but also because he’s miserable. He’s created problems for himself and others, and you need him to grow up, basically, just grow up and take some responsibility in life.

I think we all know people, never evil people, just a little bit selfish, who are just looking out for themselves and using people in small and big ways, in any way they can. I think you root for him because you identify a little bit with him. You know that not all of us have very high principles, not all of us have the courage that Asghar has. But you look up to Asghar, and somebody like Jaun also looks up to Asghar—looks up to him and knows that he cannot be him, but definitely wants to be around him, wants to be in the aura of talented, principled guys like that. What you’re really rooting for when you’re rooting for Jaun—you’re not rooting for him to win. There’s nothing that he’s won by the end of it. You’re rooting for him to grow up.

“I think we root for him not just because he’s flawed, but also because he’s miserable. He’s created problems for himself and others, and you need him to grow up, basically, just grow up and take some responsibility in life.”

There’s a lot of social media in this book. It’s how Jaun keeps track of people he knows, and it’s also how he projects an image of himself, sometimes for his work and his career, which are both ways in which most of us use social media, really. I was wondering what drew you to weave that in through The Comeback.

I have gotten onto Instagram only a month ago, so when I was writing this, it did not come from my experience of Instagram and social media, but I was observing at a slight distance. I have been on Facebook for many years now, and I’ve been on Twitter quite intensely in recent years. I look at these spaces and I also see what spaces work for whom—Facebook might work better for writers, but Instagram is definitely the place for artists, visual artists, people who want to be seen and looked at rather than just read. I was thinking about the ways in which people use social media to build their personal profile, to build their presence.

For the small independent artist, it’s actually a tool. If you’re a poet, you can put up a poem and people read you, and that’s how you build your following. For an independent artist like Jaun, it also becomes a way of seeking work. Nobody’s giving you auditions, nobody’s looking at you, but you have an opportunity to force people to pay attention to you because you can do your own audition online. And if it happens to catch someone’s eye… Maybe it’s only a one in a hundred possibility, but the possibility exists. I see a lot of young theatre people use that—they’ll go somewhere, they’ll dress up, they’ll take a picture of themselves in a new look, with moustaches, for example, or they’ll take a lovey-dovey picture with a girlfriend. If I was a casting director, I’d be looking at them and thinking, “Maybe he could do a good job of this [role]”.

We are all using social media now in semi-professional ways. I use it in semi-professional ways too. Social media has sort of become an alternative space, almost like a physical space where we go and spend all our leisure time. I think about 90% of our leisure time now goes on social media. So you can’t afford to ignore it anymore, especially if you work in the arts. That’s why, by default, I think, for our generation, and I think it’ll stay this way at least for the next few years to come, it’s going to be this way—it will become both a tool and an archive of our lives. I was kind of using it in that sense as well, to explore both the possibilities as well as the compulsions of putting yourself out there.

Names, or the absence of names, have always been really important in your writing. There are some books, like City of Incident or Love Stories #1 to #14, where there are no names for characters or places. But in other works of yours, like your play ‘Name, Place, Animal, Thing’ or The Comeback, names have such an importance. In The Comeback, the most obvious example is Jaun changing the spelling of his name to the anglicised ‘John’ when he becomes a film actor. What draws you to that as a theme generally and how you approached names and naming in this book?

With naming, I’ve always struggled a little bit. When I want to focus on the feelings that the characters are going through, and the particular moment that I want the reader to zoom in on, and I don’t want them to think about the characters’ social identities so much or to approach them through the lens of identity, then I tend not to give them names. When I wrote Love Stories or City of Incident, [I left them unnamed], because it could be every man, it could be you, it could be someone you know, and how does the name matter? I wanted that everyman quality in those texts, so I did not give them names.

I think, in a country like India, particularly, names become overwhelmingly important because social identity is immediately identifiable. Even if it’s an inaccurate identity—like in my case, when people hear ‘Annie’ they often mistakenly assume that I’m Catholic, which I’m not. Sometimes that happens. Sometimes you have a mixed identity, sometimes identity itself becomes complicated.

With Jaun, I gave him the anglicised spelling because John is basically a slightly insecure guy. He’s fighting for his place in the big bad world of [cinema], he wants to be accepted. And there is a tradition of people changing their names for the movies to become more widely acceptable—in the 1930s or ’40s, this was very common; people like Dilip Kumar, Meena Kumari, all of them had screen names. Sometimes they change the names to appear majoritarian, like Meena Kumari, but sometimes they would change their names not to indicate a different identity—sometimes it was just names they thought were a little more cool. Why this one? Why not that one? Maybe because there are too many people who have the same name. Sometimes you just want something that’s a little more edgy, you know?

“I think, in a country like India, names become overwhelmingly important because social identity is immediately identifiable.”

In the case of a name like Jaun Kazim, which is a very unfortunate way to spell it, the words Jaun and John both come from the same origin, the Middle East, basically. But if you spell it as Jaun, it is burdened in a particular way that I don’t think an aspiring firm star would like. And a surname like Kazim does nothing at all. It doesn’t have the glamour of the big Khans. It’s just something kind of ordinary. And I don’t see Jaun as the kind of guy who’s content being ordinary, who is content to just carry who he is into his work. He wants to be someone else. I think that someone like him would want a different name. At the same time, he doesn’t really want to pander, so he wouldn’t go too far from his original name either. He still wants to be a little bit like himself, but he also wants to be cooler, to give off a sense that he is a somebody in the world.

The other naming choices that I make, I make from the social context. Jaun needed to be from a place, so I made Baansa, which is a fictional place, a C-town in Uttar Pradesh somewhere. When you place people like that in those towns, then their friends will be called certain things. What will his brother be called? Families in India often give their kids rhyming names, so Jaun’s brother [is named] Aun—another unfortunate name. I gave them slightly wacko names for a reason, because sometimes your parents are not thinking when they gave you these Jaun-and-Aun kind of names.

I thought this was a nice time to ask you, since this is a book about theatre and you’ve worked so much within the medium, what do you remember being your first brush with theatre? What’s it like to look back on that now?

I think I have been performing on stage since I was very little, since I was six or seven—we used to do school dances and school productions. But I think when I was doing all these things, to me, there was no separation between performing on stage as a dancer or as an actor or as a singer, although I sang very poorly—but you know, you get shoved in the chorus anyway.

Up to the age of about 12, I was just doing things the way you were being told. Your teachers were telling you, this is a script. You have to do this, now you do this dance. Now you go here, enter here, exit there. I have no real memory of it. And it wasn’t a conscious artistic enterprise. It was only in my teens that I was part of a one-act play. I remember reading the play. It was in my brother’s syllabus; they had a collection of one-act plays, and one of those was picked up for performance. By then, I was probably 14 or 15. It was a comedy, a Mexican play—it was hilarious. I remember being cast in one of the parts, and I have a distinct memory of the theatricality of it, the drama, the way in which doing this play was different from doing another play. This is not Shakespeare, this is a comedy, it’s modern. The social context is different.

Then when I went to college, I picked up the same play. And this time I directed the show. I did cast myself, but I cast myself in a different role, as one of the minor characters. And I cast my friends—other girls in college—for the other roles. From picking up the text and allowing the teachers and other elders to direct me at 15, to 17, knowing that there is this play, I know it works, it’ll work well for a teenage audience, and taking ownership of it, saying, I’m going to direct this myself—that was my first real brush with theatre. Or more than a brush, my first deep engagement with a text.

I love to read plays. I feel like I haven’t watched a lot of live theatre, but I really like to read them. I know that it’s obviously better seen or acted, but I personally find so much joy in just reading a play, and I was wondering if you had any thoughts on reading versus watching a play.

I love reading plays. I like watching plays too, but I think that they are fundamentally works of literature—and they’re the original works of literature, actually, they were around before novels were being written. They’re very malleable as well, or at least they should be. I think people have now developed a very narrow sense of what a play should be, how many acts and so on. In the old days, there were no rules like that, right? You made up the rules. You wanted to put in a song, you put in a song; you wanted to put in a dance, you put in a dance. You did whatever you liked. You wanted five acts, you wanted seven acts, you wanted to do it all night long, you did it. If they work on the page, then they work as a text, exactly like a poem or a novella or anything else. They give you the same joy, they give you the same laughs, they give you the same sense of character, tragedy, comedy, whatever.

I think because they’re expensive to put on, we don’t get to see them realised to their full potential. Most of us don’t get to see them. The sad part is that publishers have also kind of retreated [from publishing plays]. They’ll only publish it if it has been performed, or if they see the playwright is successful, or like in my case, if it’s won a prize or something like that.

Can you imagine a world in which every town did have its own local theatre group and its own local playwright? If they were writing and adapting and translating in every city in India, we would have a much more robust play-reading culture as well. Not everybody necessarily needs to perform everything, but there’s no reason why one should not have a book of ten new plays being published in, say, every state language at least, I think.

There’s a moment in The Comeback that I really loved, which is when a young actor comes up to Jaun and is asking for help to break into Bollywood. And Jaun is thinking about how this kid will have to work so hard and have to be so scrappy, otherwise he just won’t make it. And then Jaun just thinks, “It doesn’t have to be that hard”. I just found that moment such a nice, simple realisation of the help that he has been offered and what he can offer forward. I was wondering generally how you think of community in the art forms that you have been part of, and how you thought of it within this book.

I think in some ways I have been lucky. This has not been the case from start to finish in my own career. I have struggled a bit to find community, to find people who will help. At the same time, I’ve always had writer friends. I went looking for them when I was quite young, in my early twenties. I was always looking for groups to join and places I could show up and feel like I’m also part of the community. In Bombay, it was a little more difficult for me, but online, once the Internet came, spaces started to open up a bit more and you could find people, especially people who were just starting out like yourself, who weren’t yet published. I did make friends that way. And I always had writer friends even in college, and I still am friends with some of those people.

With theatre, especially, but also with books, I think you can’t really do without your friends. You need that community. You need them to make your work better. In theatre, you just need them to make things happen. You can’t do everything yourself. You can’t play all ten parts on stage yourself. Learning to work with the group, learning to negotiate egos, learning how this thing works, actually—how a group can come together to make that small, little, brief bit of magic.

“With theatre, especially, but also with books, I think you can’t really do without your friends. You need that community. You need them to make your work better.”

I’ve also had the experience and privilege of watching other people on the professional stage, where there is a lot of solidarity. I saw how people allow themselves to get shaped. For an actor to trust a director, to surrender some part of themselves to the process, to allow their bodies and minds to be used in a particular way, is an act of trust. And I’ve seen the way people trust in these people even beyond the stage—it’s not just that moment. Most people in theatre will have friends in theatre; similarly, most of us writers have friends who are writers. And that’s how it works. You still also have friends from other communities and other professions, but the sense of community is vital. You need it to grow and you need it to sustain you and you need to do your bit to sustain it. You need to show up for them when they need you as well.

In the context of the book, this is a lesson Jaun has to learn. You don’t just take and leave. His journey is really about understanding that it’s not just all about you. And also to remember that the mistakes you have made, some of those mistakes have come from you only looking after yourself, and only thinking of yourself. So when there is an opportunity to collect yourself, and to stop yourself—he could have done the same thing as before, but he had the opportunity now to change that.

What is your writing process like?

My process is usually all over the place, but I’m a little bit old-school. I’m mostly just about “sit there and write something”. I don’t always write creative things all the time. It’s not like I’m always working on a novel—most of the time I’m doing a little bit of drudge work as well. Sometimes that’s just stuff you have to do for a living. Sometimes it’s my own journaling practice, just sitting there and taking stock. Sometimes it’s trying something new.

I sit down and I say, okay, I haven’t written something for a long time. I should try and write something. I write a page. Two days later, I look at that page and I say, this is not going anywhere. Don’t dig yourself in deeper. Just pick it up and toss it out. A lot of my writing is also that. Trying and failing. And that doesn’t change: even after twenty, twenty-five years, I’m still trying, still failing. A lot.

A lot of my work is not going to be published, I know. I’m doing it as practice, so I do it. Out of that practice, something good emerges. Like this novella, for example. I wasn’t trying to write a new novel. I just needed to cheer myself up; I needed to write something that gave me joy and optimism. They say write for yourself, which means writing not just to express yourself, but to write the things you want to read. That process is actually just allowing myself to trust in that moment and that feeling. Sometimes that feeling is very different; City of Incident came from a very different mood, structurally and emotionally. For The Comeback, the impulse was seeking joy, seeking hope, seeking second chances. The practice kind of follows the emotional quality of that moment in which I started writing.

“A lot of my writing is also that. Trying and failing. And that doesn’t change: even after twenty, twenty-five years, I’m still trying, still failing. A lot.”

In your writing, do you often see yourself intrigued by similar questions or ideas? Are you drawn to similar themes over the many years that you’ve been writing?

Some patterns repeat. The question of identity and belonging, I return to it a lot in my nonfiction. Sometimes in my fiction too, but more in my nonfiction, because that feels like a more direct and personal question for me. Where my place is, concepts of home, concepts of how I define myself, how my country responds to me—these are questions I keep returning to.

A lot of my work is shaped by cities, [directly or indirectly]. City of Incident is most directly about cities, but I am drawn to particular places. Prelude to a Riot is also a very place kind of novel. Everything that takes place there is about that town. In many ways The Comeback is also like that. It’s a fictional small town, but it is very much a novel about place. Sometimes I narrow down a place, whether it’s real or fiction, and become a bit attached to that idea and keep working around it until it becomes a strong [backdrop] and I need to tell the story of people in this place. I am becoming more interested in history now. It comes up sometimes in my work, for example, in my play ‘Untitled 1’ and in Prelude in a tangential way. I find myself reading more history now, though I don’t know if I’ll write more history. Maybe in the future.