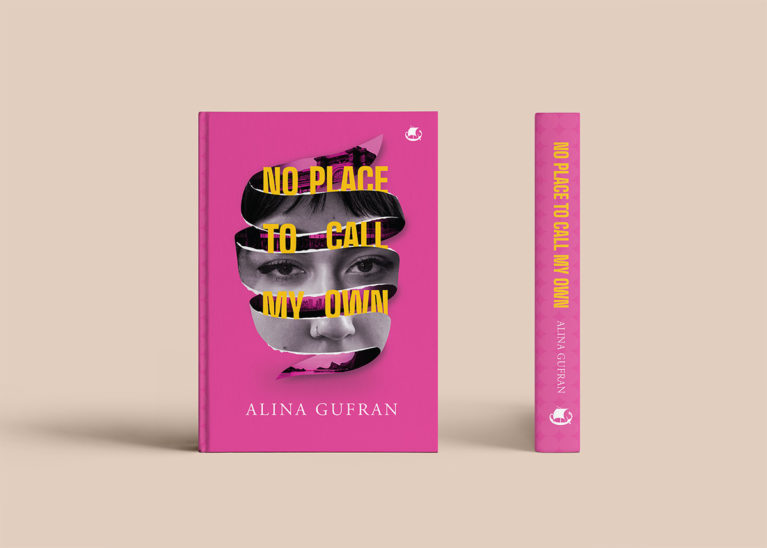

In Alina Gufran’s debut novel No Place to Call My Own, we follow a young woman, Sophia, across countries, cities, and apartments as she searches for a place she can belong to. She becomes entangled with different people at various points in her life—men she meets and shares relationships with; her best friend, whom she clashes with on and off; her parents, who occupy a background presence. As the spaces and people around her change, the only constant is Sophia herself.

No Place to Call My Own is a novel-in-stories, told in snippets of Sophia’s life across her twenties and early thirties. Alina Gufran spoke with Helter Skelter in an exclusive interview about drawing inspiration from real life, creating intimacy between reader and character, and how her experience as a filmmaker helps her write better.

How did the journey of this novel begin for you? At what point did you realise that you had a book?

I’ve been writing prose my entire life. I actually started developing this as a collection of short stories, which happened during the pandemic. I was primarily working in the film industry, writing, directing, doing a bunch of things, as everyone does in Bombay, and the pandemic hit, and all projects came to a standstill. And this is a very privileged thing to say, but it was a bit of a boon in disguise. It also coincided with my complete disillusionment with the Hindi film industry, after many years of just writing commission scripts for other directors, which is a very particular kind of writing—I’d been developing my own work on the side, but it never just saw the light of day. I hadn’t shown it to anyone.

So it really started with one chapter, chapter three [‘Prague’], which came to me out of nowhere as a story deriving from my own experience in film school. The incident [that takes place in chapter three] is completely fictional, but the characters are loosely derived from the coterie of interesting people that I met in film school. I obsessively wrote the story for about three months. I kept editing it and trying to crack the plot. I sent it to a few peers, and the feedback was really good. I wish I could say I’m above external validation, but I’m really not. That gave me the motivation to continue writing. And then other bits and pieces started emerging. At some point it became clear to me that the voice across all these little snippets was the same. What was compelling to me was the character that was emerging, and her voice, more than anything else.

Then I figured that I could just focus on this character, and I could practically make her do anything, make her go anywhere, and contend with anything, because I feel like her perspective of the world and who I think Sophia is, or what she symbolises, was exciting to me. And then between early 2020 to 2023, when it got picked up by Westland, it was just the writing and the rewriting.

Each of the chapters in your book is named after a place that Sophia lives in or visits, as she seeks a place to call her own. How did you arrive at this structure, and what was it like to flesh that concept out?

The idea of her trying to inhabit various spaces was extremely important to me, because for Sophia, her main contention is a sense of belonging—to something or someone, an industry or her practice, even belonging to her best friend. And I feel like most of her contradictions and tensions in her life come from that place. They come from that inherent tension of who she is.

There were a couple of reasons as to why it was structured across several cities. One was quite technical: to give it a certain momentum and pace and a certain manipulation of time, which I also like to use as a reflection of her mental state. I could manage to fit in more in terms of an odyssey or a character’s journey if I was to experiment with place like that. Another reason was that I wanted to show how her journey from being hinged on factors outside of herself slowly changes with time, and how she arrives at a place where the time and the place become immaterial because the sense of belonging is finding its first feet within her. At the end of the book, it’s not like she’s arrived at that, but you can feel the first stirrings. That journey for me and for the character became really important.

Each chapter is more or less centred around a particular event or moment, and a reflection on everything around that perhaps has brought her to that moment. That, to me, created a sense of richness to the story and a sense of dramatic irony, because quite often, she could be meditating on something that’s happened in her school that doesn’t concern her at all, because that’s her way of looking at the world. What she’s really trying to do is look for answers within, or look for answers to her own pursuits. Turning this lens outward in this obsessive need she has to dissect everything around her and then relate it to her own experience, to me, felt like an interesting sort of thing to tap into as a character. Her concerns seem valid to me, but she is quite self-absorbed. So it’s interesting—it speaks to, perhaps, the generation we belong to, because a lot of the external concerns eventually become a mirror as well as a window to the reader, and speaks for myself, to my own concerns as an author and as a person in the world.

“My hope is for the reader to feel like they’re inside Sophia’s head.”

I know that some of the chapters in your novel have been published as standalone pieces online, some as early as 2020. How do you look at these pieces on their own versus in the context of your book?

I haven’t really looked at the standalone pieces for a very long time, not since the first or the second draft. There’s a lot of information threaded through the novel that, for me, felt important to reveal in chapter three, and not chapter one. The way I’ve written the story, or the way I’ve tried to capture Sophia’s voice, is to keep the point of telling or the voice as extremely intimate. It’s almost like she could be writing in her diary, or she could be narrating the story of her life to her best friend. And that’s a particular voice I’ve tried to retain throughout, so there are certain things I don’t want to translate. I haven’t used dialogue tags. And these have all, honestly, been battles, because it’s not very traditional. These were all very conscious decisions that were made to maintain her voice in a specific way. At no point did I want the reader to feel like the author is present on the page, or to feel like they are too far away from Sophia at any given point. My hope is for the reader to feel like they’re inside Sophia’s head, contending with the ten different things jumbling around in there. That’s really the kind of experience I wanted to create, more than anything else.

I think there’s subtle progressions in her relationship with her mom, her dad, her work and her best friend, Medha, that kind of happened through the book, which kind of become the emotional spine or the engine around which the novel hinges. The rest of the things that she ends up contending with are more symbolic of where she is in her life at the moment, and a comment on her evolving relationship with men, or work, or the sexism that she faces.

How do you approach editing your own work?

I am a very haphazard writer in that I rarely ever have an outline. I rarely have a structure. I actually have a running document on my laptop, where anything that strikes me, I just write it. I try not to be inundated by story so much. I feel like that’s very secondary to me. I try to give space for characters and the voice to emerge. And preoccupations: what is the character’s preoccupation? What is something that one can sit with for five to six years? In this particular case, it becomes identity and belonging and displacement and coming-of-age. For the next novel, these concerns might change. They’re also reflective of my concerns, given where I am at a certain moment in my life.

I think I’ve gone through each chapter about a hundred, two hundred times. I don’t know if there’s any particular rule I follow, but I try to trim the extraneous as much as possible. I try to not get caught up in language. Of course, language is extremely important, but in the editing process, I try to say less. The tendency can be to want to add more, to over-explain. But I do feel that by the time you’re on chapter five or chapter six, the reader has made their assumptions. They’ve invested the amount they had to invest. So I try to respect that about the reader, and I try to trim the fluff as much as possible. This is more from a line-editing point of view.

Structural editing is a beast! If I’m doing developmental structuring, I’m prone to Venn diagrams and charts, and I try to map out the protagonist’s relationship with each character. This is, I think, a screenwriting thing that I’ve picked up from school, where I’ll map out all aspects, including a backstory—I’ll go through questions about each character, down to what their favourite podcast is. Whether that information makes its way to the novel or not is immaterial, but for me as an author, it’s important for me to know these things, so I know how the character will react. I try to let the character dictate the story more than anything else.

I don’t ascribe very much to logic after a point in storytelling, although I understand it’s inherent to a good story. If you’re able to craft a compelling character, even their contradictions are believable, because that’s just how people are. Linearity is not something that people really function on the axis of, even in terms of thoughts or the way we feel about a certain thing. If I know the character that deeply in the story itself and the contradictions arise, I’m able to make sense of them and I’m able to flesh them out.

You mentioned drawing from real life—I feel like there’s sometimes a tendency to assume that if you’re a writer creating a character that is similar to yourself, that means that you believe the things they believe, or that you are like that. There are some biological or environmental things you share with your protagonist, like where you studied. I was wondering how you approach taking inspiration from real life in your fiction, and if you have faced this conflation of character and author.

I think this tends to happen quite a bit, and people always want to know how similar or dissimilar the character might be to the author. What people don’t realise when they ask that question is that in order for me to craft a character exactly like me, I would have to have that degree of self-awareness, which I absolutely do not.

Obviously, some traits or certain physicalities or mannerisms are constantly being perceived and picked up on from the environment. I derive a lot from the environments I inhabit. I’m quite a sponge, and I tend to really immerse myself wherever I am. I don’t know what that says about me as a person. I think it’s a difficult way to live life, but I think as a writer, it really helps, and the rest is just pure dramatisation. There’s also a bit of lying in there, because you can take a character—let’s say I vaguely met someone and I found something interesting about them—I will steal that, make that into a character, and start embellishing it with how I perceive them. It’s got nothing to do with who they are. It’s purely my perception. So there’s a bit of that as well. I’ve actually reflected on this quite a bit; I’ve always wondered if novelists or writers are really just control freaks, because we’re trying to manipulate so many lives when we’re writing.

“I don’t ascribe very much to logic after a point in storytelling, although I understand it’s inherent to a good story.”

I tend to want to write characters that are grappling with things that I might be grappling with, because I just feel I can do justice to it. It also, for me, becomes a way to interrogate my own concerns. It’s not as if I arrive at any answers at the end, but in some delusional way, it feels like a knot has been loosened.

When I sit down to write, I’m not thinking about any of this, really. I’m just thinking about what’s gripping me at the moment, and I want it down on the page, and after a point, it has its own life. It takes me somewhere. It’s rarely ever where I expect to go. But then it takes me somewhere else, and then something else emerges. It’s like I’m constantly in conversation with my own work.

That’s such a lovely way to phrase it. Your book is set in urban India, and it focuses on a woman’s story and foregrounds her relationships—I don’t think I’ve read many books set in India of that sort. Were there works that you looked towards for inspiration?

I think more than inspiration, it’s just a matter of reading habits. I think what helped me, weirdly, was the fact that I haven’t studied literature, and I haven’t formally studied literary theory, so there was never any conception of who I’m supposed to read. At some point, I think when I was about fourteen, I was like, ‘Oh, I only have male authors on my bookshelf.’ I just switched one day. I just, very voraciously, started reading women, across the board. And that became the diet over a very long period of time. I don’t have to think about it now; it’s just second nature.

I think a lot of writers and authors who have inevitably influenced my work ever since I was a young person—so not this particular work, but also just my pursuits and aspirations as a writer—would not be people who are really considered part of the canon, because that was not really the time where women were given that sort of mantle. It would be a stylist or a modernist like Alberto Moravia or Shirley Jackson or Mary Gaitskill or Annie Ernaux.

I’ve also been greatly inspired by a lot of contemporary writers who are doing a very interesting job in marrying literary fiction with genre—they’re telling stories which are essentially, for lack of a better word, highbrow. They’re concerned with people more than anything else, but they’re also using genre mechanics to tell those stories, which is very exciting for me. Olga Tokarczuk is a very good example of that, especially Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead. Or writers like Alexandra Kleeman or Han Kang. I also had a huge Latin American literature phase, which did end up influencing me a lot—a lot of Cortázar and Borges, and now in the current scenario, Mariana Enríquez. There’s not a lot about the way these writers write [or the kind of topics they address] that you’ll find in my novel, but I think the way they do it, their form, the concerns, the actual language itself, the particular construction of sentences, is something that has appealed to me over the years.

In terms of Indian novels, frankly, I feel I would not be the right person to be able to comment on this book vis-à-vis the larger South Asian landscape of literature. There’s so much I haven’t read. A book that stands out in recent memory is Avni Doshi’s Burnt Sugar. I think I found it at the right time, and I was really excited to read something like that—to read about motherhood in such a contentious manner, and in the voice of somebody who really wasn’t afraid to be seen as bad. I enjoy that because I just don’t think literature is the realm for politeness. I think Avni Doshi also did this particular thing with language, where it was very staccato, very pithy, not necessarily lyrical, and yet it managed to capture so much and say so much. Another one would be Deepa Anappara’s Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line. A stunning book, so different from what I’m writing, of course, but still felt like a watershed moment.

I do think a lot of the concerns [in my book] are so zeitgeisty—you know, there’s the pandemic, there’s social media, there’s all of that. So maybe people are writing [stories like this] and we haven’t heard about them because they haven’t reached the right editors yet.

“When I sit down to write, […] it’s like I’m constantly in conversation with my own work.”

What was your own journey to publication like? How did you find your agent and how did your book make its way to Westland?

I wrote to Ambar [Sahil Chatterjee, an agent with A Suitable Agency], who, frankly, has been my North Star during this whole process. I know a lot of my peers and some young writers I have spoken to have had their doubts about agents, but especially as a debut author, I could not recommend it more strongly. When A Suitable Agency expressed interest in my work, for the first time, I felt like writing books could be a reality—it felt like my writing had legs. Until then, I had no conception of my prose in a commercial sense, I had no idea of what that even looked like. All I knew was I wanted to write, and it was really quite naive, to be honest.

In due course, Sangha [Sanghamitra Biswas] came across it at Westland. I met her briefly in Goa, and it was really like finding the right fit, because we had about two hours where we chatted about every aspect of the novel. There were things she managed to articulate that I hadn’t even articulated to myself—they just existed in the aura of the story somewhere. 2023 was when I got signed on, and now the book releases in January 2025.

You engage in many different kinds of writing and creating—fiction, essays (you even have a piece on Helter Skelter), a podcast, and you write a personal newsletter. And, of course, you also work as a screenwriter. How do you negotiate these different forms of creating?

It’s interesting, because I feel like I’ve always wanted to write books. Films are very demanding too, but it’s very different. The energy is very different, because it’s very director-led. I’ve also been in directorial positions, and after a point, once the script is done, you have a team of thirty people supporting your vision. It’s like everyone’s working with each other to realise this vision. I think a true strength of a director lies in recognising the right people for the right roles—the right cinematographer or the cast or the editor, and then being able to have enough faith and trust to delegate that. So, really, it’s always a team that brings it to life, even though in the press or the way it’s perceived by the world, it’s very much always a director’s vision and baby.

The rest of my pursuits, nonfiction, podcasts, it’s really just a whim, sometimes—and I acknowledge the privilege of being able to say that. I’ve always managed to somehow hold a day job and write, but that very much comes at the cost of many negotiations with your personal life, such as making a certain amount of money or living a certain standard of life. Now I’ve arrived at a point where I don’t really feel the need to explain that. And luckily, I’m from a family that supports this constant negotiation. They had their doubts for a long time, but I think now we’ve arrived at a point where they’re like, ‘Okay, we don’t really know what she’s up to, but some of it is beginning to make sense.’

I’m nowhere close to being able to sustain myself just through writing books, although that is the eventual aim. I also have a very interesting relationship with films because it’s a big love, and I’ve also formally studied it. The thing with certain kinds of formal education, with any creative art, can be that it does make you a little didactic, a little pedantic, a little like set in your ways. I definitely think I’ve had a bit of a chip on my shoulder as far as filmmaking is concerned. Also, the stakes are very different. There are crores attached. There are constant stakeholders to impress. The realities of the industry [in India] are very different from how film is practised abroad, primarily because we don’t have enough public funding. Public funding makes a huge difference, because it really does give you the space to make whatever you want to make as a young filmmaker. In India, spaces like that are extremely limited. The landscape is changing now, but not so much, and very slowly.

“I feel like when I write, or when I finish writing a piece, something within me changes, and I’m hoping that when a person reads my writing, something within them shifts.”

With scriptwriting, the demands are very different from prose, but I feel like so much of my education in film and my work there has informed my writing. Even simple things like telling the story in the white spaces, or how I might choose to transition from one scene to another, works very differently for me because of my experience in screenwriting and editing. I actually have a very abusive relationship with filmmaking. It’s like a bad relationship. Every time things are good, I’m like, ‘Oh my god, this is it. I love this. Everything about this feels so good.’ And the minute there’s the first obstacle—and it’s really quite rife with obstacles—I’m like, ‘This is the worst. I should have never gotten back to it.’ But I don’t see myself moving away from films. I would like to write and make films for as long as I can.

Fiction, for me, is a very sacred private practice. It’s the closest to who I am as a person, and it feels the most visceral. I feel like when I write, or when I finish writing a piece, something within me changes, and I’m hoping that when a person reads my writing, something within them shifts. Films can have that effect, of course, but with prose, strangely enough, because it’s closer to home and it’s closer to me, it feels more expansive.