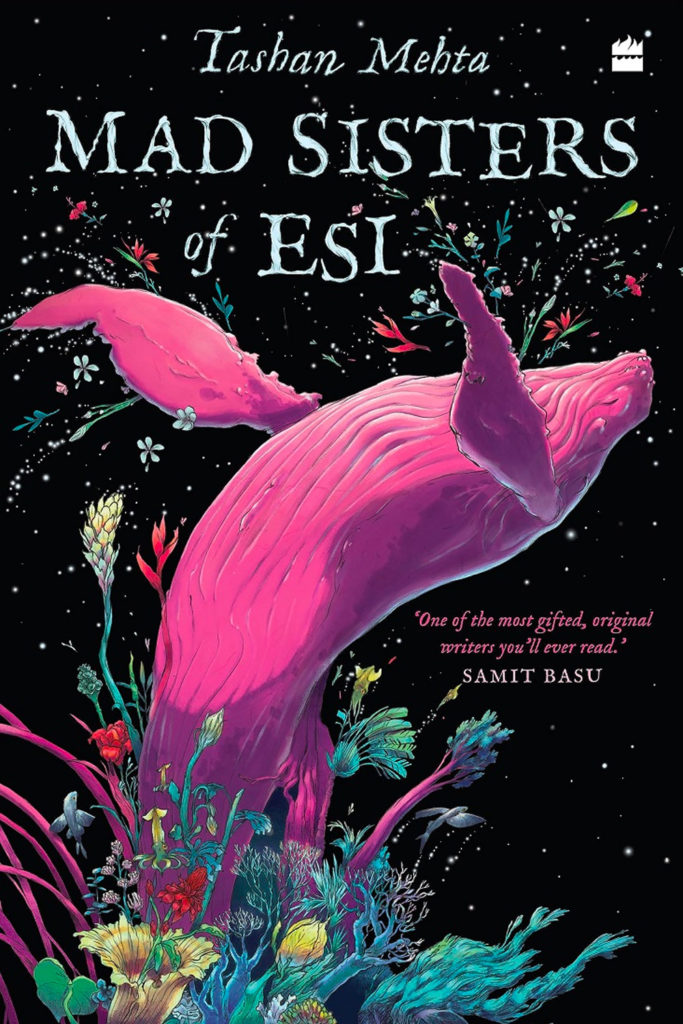

In Tashan Mehta’s Mad Sisters of Esi, islands are alive, memories are dimensions we can navigate, and the universe is a sea on which ships of discovery sail. Two sisters—Laleh and Myung—live within the whale of babel, which houses unimaginable worlds. But Myung wants to leave. Her journey leads her to other islands, inhabited by friends, foes, and ghosts, and to the story of another pair of sisters whose lives intertwine with hers in stunning ways.

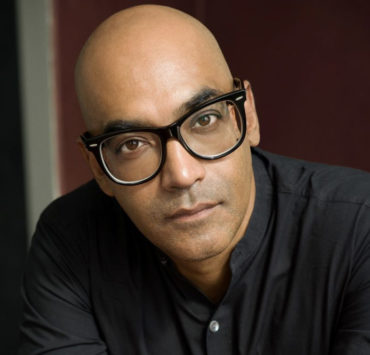

Mad Sisters of Esi is the newest instalment in Mehta’s wildly imaginative writing, following her debut novel, The Liar’s Weave. Combining expansive cosmic wonders with the careful, real power of human relationships, Mad Sisters reminds us of the strength of bonds between people, the power of stories and myths, and the wonder of the natural world. Tashan Mehta spoke with Helter Skelter about looking at the world through fresh eyes, talking to her past self, and the process of building new worlds from the ground up.

Your debut novel, The Liar’s Weave, was a fantasy novel that was anchored to the real world. In Mad Sisters of Esi, you’ve built an entire universe from scratch. What was that process like?

There was a question in the process of writing Mad Sisters—how wild do I go? For a long time, I fought it. I tried to put it back into the real world to the best of my ability. I think I got to a point where I couldn’t do wildness well enough within the confines of reality. You can see that in The Liar’s Weave as well—this desperate attempt to make something new from the bones of the old. So I decided to just go with it. To be honest, it’s entirely what the idea wanted. It needed a whole universe that was made entirely for it. I tried to argue with it, but this is the direction it needed to go. Mad Sisters of Esi was just me talking to my imagination a lot.

When you build a universe, it’s not just worlds you make up. It’s also complex histories, fairytales, and fables. What kind of research did that take? What was the process of worldbuilding like for you?

It took a very long time to write this book: five years, twenty-four drafts, and five different versions. The generative power of endlessly writing it managed to throw up enough histories and enough myths. Non-humans are very integral to this book, so I was also trying really hard to understand, what does non-human language look like? I read an absolutely beautiful theoretical book called How Forests Think [by Eduardo Kohn]. There was a lot of trying to understand how forests think, and trying to get into non-human ways of thinking. There was also a lot of analysis of fairytales—trying to get to the heart of what myths can do, what histories can do, and what happens when they morph. Mad Sisters of Esi cares so deeply about the interpersonal and the personal. It was really important to me to take the cosmic and squeeze it down into this tiny little space. Histories matter so much to human beings. It matters so much where we come from, the stories we tell about ourselves and our families, how we even narrate ourselves to others. It was fascinating to do this larger worldbuilding and knit it back into the very tiny conversations we have everyday, as families and as people.

Did you do have a larger sense of the universe than the reader is exposed to in Mad Sisters? Was there a lot that you wrote that didn’t end up in the book?

Yes, but that was largely because I assumed it would end up in the book! In my very last edit with my publisher, I took out a whole academic essay—a 6,000 word academic essay on madness. It just didn’t work with the pacing of the novel. I’ve replaced it now with something else, but I remember it cracked my heart open to pull it out. I always worked with the assumption that whatever I wrote would be in the book. I never world-built independently.

My style of worldbuilding is very much inspired by M. John Harrison’s style of worldbuilding, where he talks about the generative power of language. You don’t build the world and then place your characters in it; you discover the world as you write. You see what language throws up, and what it tells you. While writing Mad Sisters, just calling the universe the ‘Black Sea’ made such a difference for me. It meant that it felt adventurous, it took me back to quests and stories that I absolutely loved. It got me excited. I needed to feel like we were going through uncharted territory. I needed to feel like the ships were the old-fashioned sail ships that I read about in fairytale books. It’s so interesting how the language you use works for the readers, but is also integral for you, the writer, to place yourself in the story. I kept looking at what language can do to dissolve our boundaries of how we see the world and how we encounter it. Basically, I made it up as I went along.

“It’s so interesting how the language you use works for the readers, but is also integral for you, the writer, to place yourself in the story.”

Why did you zero in on a whale, of all the structures or animals you could have chosen?

It was originally a tower: the Tower of Babel, very much inspired by the story. As non-humans gradually became more and more important to the story, I realised that it would have to be a sentient being. A tower reminds you of something man-made, even if it’s thinking and talking. I wanted to sidestep the centrality that we often give ourselves in narratives. A whale felt far more evocative of the adventure stories I read, like ones of people caught in the belly of a whale. There’s a lot of echoes of me going back to my childhood self, taking what she loved and putting that same imagery into the book.

I thought it was interesting, in the context of the story of the Tower of Babel, the idea of these sisters sharing a common language and then ending up scattered across the universe in a way. How did you come to that story?

One of the biggest preoccupations of Mad Sisters of Esi was asking myself different ways of seeing. What is it like to look from various different angles? I used different ontological stances to try and get that in there—diaries, first-person, third-person, dreams. The whale of babel is a massive physical manifestation of what it is like to have these numerous different ways of seeing. Myung and Laleh are raised on a language and on a way of viewing the world that is not familiar to us. They were raised by the context around them that is essentially just chaotic, and mad in many different ways. What happens if you start with two characters that don’t talk the same language as we do? What does that do to their interactions with the wider world?

While I was reading Mad Sisters, I was reminded of a line from the 2018 film Annihilation. It’s about characters encountering an alien intelligence that many see as being an evil, destructive force. One character reframes it, though—instead of seeing its actions as destruction, she sees it as “making something new”. I kept thinking of that as I read your book. Why did you decide to write about worlds that were so alive, reactive, and constantly changing?

One of the concepts I adored in university was creative destruction: this concept of creating and destroying consistently, and how destroying something is not the end, it’s only the beginning of something new. I absolutely adored that idea. As human beings, it’s really hard to look that in the eye. It’s really hard to grapple with something we find stable and beautiful being broken up around us and morphing into something else. I’ve seen that in interpersonal relationships—you grow apart, you grow different, and then you have to try and find a way to grow back towards each other. For me, all of these worlds being alive was a crucial reminder that things are larger than us. You can view it from the lens of “they’re trying to kill me,” but they’re just doing their thing. You’re not central to their narrative at all.

What you see as destruction from one angle is just change from another angle. What you see as cruelty from one angle is just people operating on a different path that you can’t understand. I found that really interesting, the angles in which you can look through something.

There’s a moment in Mad Sisters where someone describes an island, Ojda, as being a developing island, growing from a “helpless baby” to a “tantrum-throwing toddler”. I found that so fascinating, that view of time that decentralises the one person that’s living on the island, who is actually tiny in the context of this massive span of time.

I found that deeply, deeply interesting! I read a book called Timefulness [by Marcia Bjornerud] that talks about how human beings are deeply inadequate to solve the problems of climate change we’ve created, because we don’t have the right perspective of time. The time perspective is billions of years, and we’ve got about a hundred. It’s like a mayfly trying to write the history of the human race – it’s just not going to work out! There’s a really beautiful poem that says “I prefer the time of insects to the time of stars”—I think that’s just absolutely gorgeous. That was really interesting to me, the dissonance of time you’re consistently encountering when you live in these large cosmic worlds. They are working on scales you cannot possibly imagine. There is a point in Mad Sisters in which a character has to confront her smallness: how tiny she is in the vastness of the universe, and how petrifying that is.

Time is malleable in Mad Sisters. Characters are haunted by the ghosts of their futures, for example. The book also features a place called the Museum of Collective Memory, which connects sound to the visual, and the structure is described as being “made of song”. How did you approach time, space, and sound in your book?

I approached time and space in similar ways I approached it in The Liar’s Weave, in that it doesn’t really exist! They’re constructs we’ve made in order to survive the chaos around us. And if it’s a construct, then you can play with it. And if you can play with it, you can have a lot of fun with it.

Throughout my life, I think about talking to my past self or talking to my future self. It’s incredibly powerful, because of how they see. In my early twenties, I made a list of things that I thought would be a sacrifice, that would be the worst thing in the universe to ever happen to me. Now, all of those things have happened, and I chose every single one of them. It’s interesting how much you’ve changed! Playing around with time allows you to deal with that dissonance of self—that movement of self, watching how you unfold across time.

“Time and space are constructs we’ve made in order to survive the chaos around us. And if it’s a construct, then you can play with it. And if you can play with it, you can have a lot of fun with it.”

With sound, I always feel like a little bit of a cheat, because I stole the idea from my partner. I’m awful with sound: I listen to the same pop songs, I can’t hold a tune. But he’s madly in love with sound. We got together when I started this book, and the way he talked about sound was one of the most romantic things I’ve ever heard. It was like it was alive; like it moved, like you could see it move through his body. I still couldn’t feel it myself, but I fell a little bit in love with the concept of it. It was so interesting to step away from the visual and have sound be front and centre in the Museum of Collective Memory.

Both your books place sibling relationships in the centre. In Mad Sisters, especially, there are several dimensions you explore outside of a traditional sibling relationship; bonds forged by blood, by choice, by parental decisions. What draws you to that relationship?

I think it’s one of the richest relationships you can have in your life. You start off with them—if you’re the younger sister, they’re already there. You grow up with them, and you didn’t choose them. They are family. But they’re also friends. They understand at a level your parents cannot, because they’re encountering the same world you’re encountering at the same point in time, whereas your parents lived it at a different point in time. I find the depth of that really rich.

I also find with siblings, comparisons abound. You’re defined in relation to each other. How interesting it is to have this reflection you didn’t choose and you didn’t ask for! Nobody wants to be the reflection of each other, but you are. How do you navigate that? Once I started digging a little deeper into that wealth of emotion, I started thinking, what does this look like if we complicate it? What does it look like if we take it through different angles? How does that bond hold up? How do you re-forge or re-understand it? Later in the book, there are sibling relationships that fall apart because one has been unable to change, while the other needs to change. It’s so rich. As a writer, all you’re doing is you’re sitting there and thinking to yourself, what is interesting? What is thorny and complex and knitted together in me, and what do I need to press and pull apart very slowly? I think sibling relationships are just a bottomless fountain for me that I can always go back to.

Were there differences in your approach and your process in writing The Liar’s Weave and Mad Sisters of Esi?

They were absolute apples and oranges! With The Liar’s Weave, I’d just come out of Warwick University, and I had a very strong idea of what it meant to write well. I love that book so much, but I wish I was a little bit wilder with it. I think it got put into boxes because I came with that idea. It was a lot of giving myself permission, a lot of thoughts like “I can’t do this, I’m not allowed”, and consistently negotiating that. It’s such a testimony to the strength of the core idea and the brothers’ relationship in The Liar’s Weave that it shines through despite all that nervousness.

What happened with Mad Sisters is I reached a point where I thought, you know what, nobody knows what they’re doing. There is no “am I allowed” or “am I not allowed”—they are all making it up. It is all one big, grand con. How do I approach this, then, with the same perspective of an explorer? How do I approach this with the perspective of someone who treats her idea with the respect that it deserves, and as something separate from her that is using her as a medium to get onto the page? It took five years because I was teaching myself again how to listen. I don’t think I’ve ever done that before. It was daunting. That first draft is so different from the final draft—you can see how my brain, and my approach to language and ideas and structure are changing in each draft. The final product is just an expression of “this is not the right way to write a book, but this was the only way to write this book.”

“It is all one big, grand con.”

One of the biggest concerns for me—and I think this is going to be true for every book I write—is you stop being the person at some point that can write the book, and so at some point, you start writing against a deadline. The clock is running out. You’re going to change very soon, and you can’t re-access the idea when that happens. You have to get it on the page. I wrote the semi-final draft in two months—that was just a race against time. I knew once that clock turned over I wouldn’t be the same person.

I always feel like the book is always already there. All your rewriting is just trying to become the right person to write the book. It’s trying to redo your brain so that you’re thinking in the right way to access the heart of the book.

Your writing in Mad Sisters of Esi has been compared to non-fantasy writers like Calvino and Ferrante. How do you think of your writing in relation to other works that aren’t necessarily in the genre you’re being marketed as? Were there works you looked at specifically for inspiration?

A lot of [internal] conversations that I have when I write my books are with literary authors. They are with Ann Patchett, or Lauren Groff, or Sally Rooney—how they use voice, or what they do with interpersonal relationships. I have thought about just doing a full literary book. But I just can’t keep magic out of it! I’ve come to the conclusion that the way in which I see the world involves magic to that degree, so it has to be there front and centre. But the dialogues I’m having are with writers who are traditionally marketed as literary—and I want to emphasise “marketed as”, because some of them are very much writing fantasy. Cloud Atlas is a fantasy novel. It is just marketed as literary.

“I think sibling relationships are a bottomless fountain for me that I can always go back to.”

A big conversation I was having for Mad Sisters was with Calvino. Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium was extremely formative for how I was writing, and Invisible Cities was a huge influence. He showed me how you can take the imagination, squeeze it down, and layer it beneath the language. Then you can just lift the language so that the whole thing is light. I don’t know how he’s done it! Every single one of those tiny cities [in Invisible Cities] is a universe, essentially. It gave me the permission to say, I don’t need to write a trilogy, or nine books, or expand this universe, or give you maps. A paragraph can be a universe. Your brain is going to do all the imagining for me, and that’s fantastic.

I believe so much of a book is in the voice. If you can find the right voice, then you’re fine. Calvino helped me get there. I was also going through phases where I was reading a lot of female authors—Lauren Groff’s Matrix, Ann Patchett. I was reading a lot of women that were looking in a way that I found really beautiful. The way that they took that perspective and knitted it into language is a huge skill, and I found that was what I wanted to have a conversation with in this fantasy world. How can I do that kind of personal and interpersonal relationships in the large cosmic universes of Invisible Cities? That was sort of the construction of Mad Sisters.

No spoilers, but The Liar’s Weave and Mad Sisters of Esi both end on a bittersweet note. You’re not afraid to lean into a sad or tragic moment, but you also keep it full of hope. How do you approach endings in your writing?

I think in both cases, the ending was actually written last. In The Liar’s Weave, when I wrote the last chapter, I didn’t know what was going to happen, and with Mad Sisters as well, I sort of stumbled across the ending. It ended at various different points, and I kept going until I found that perfect balance of tragedy and hope. It’s exactly what we were talking about earlier, about endings being beginnings. If you knit both of those things together, then they’re both tragic and they’re both hopeful. I’m just really interested in that. I’m interested in books that don’t tie up necessarily, and leave that crack open for more. One of the most beautiful things that a book could do is inspire a reader to imagine further, inspire them enough, and allow them to live in the world enough so that their imagination wakes up.

In both books, the idea of endings and beginnings knitted together make it tragic and hopeful. It’s complicated! Everything’s complicated, so it’s nice to end at a complicated place.