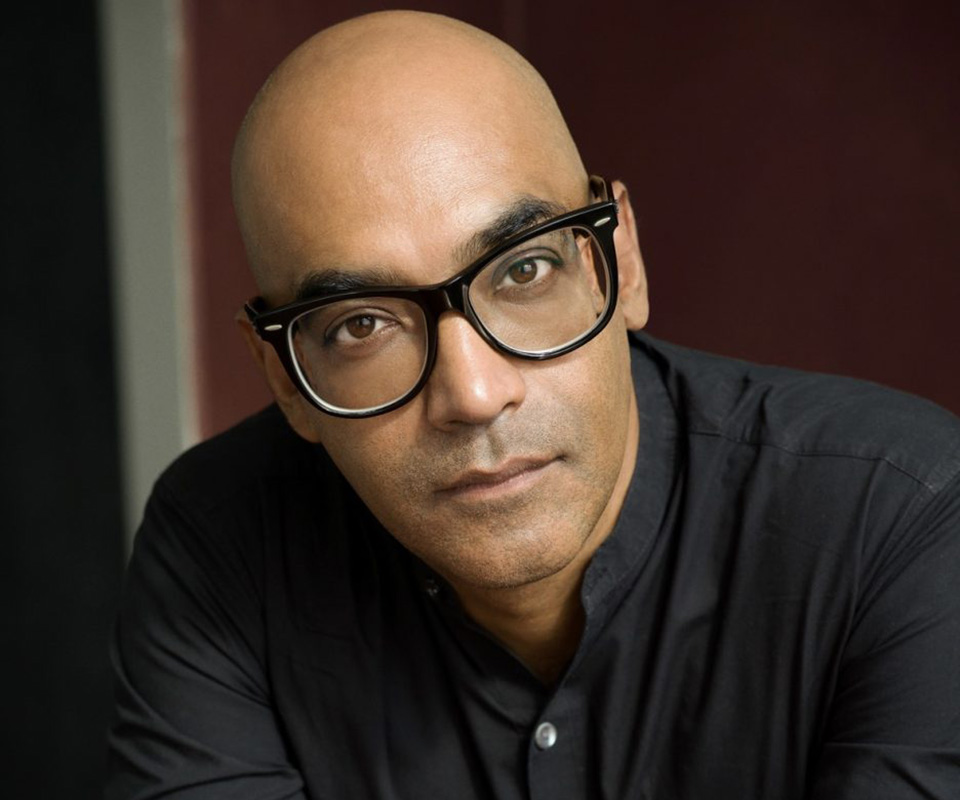

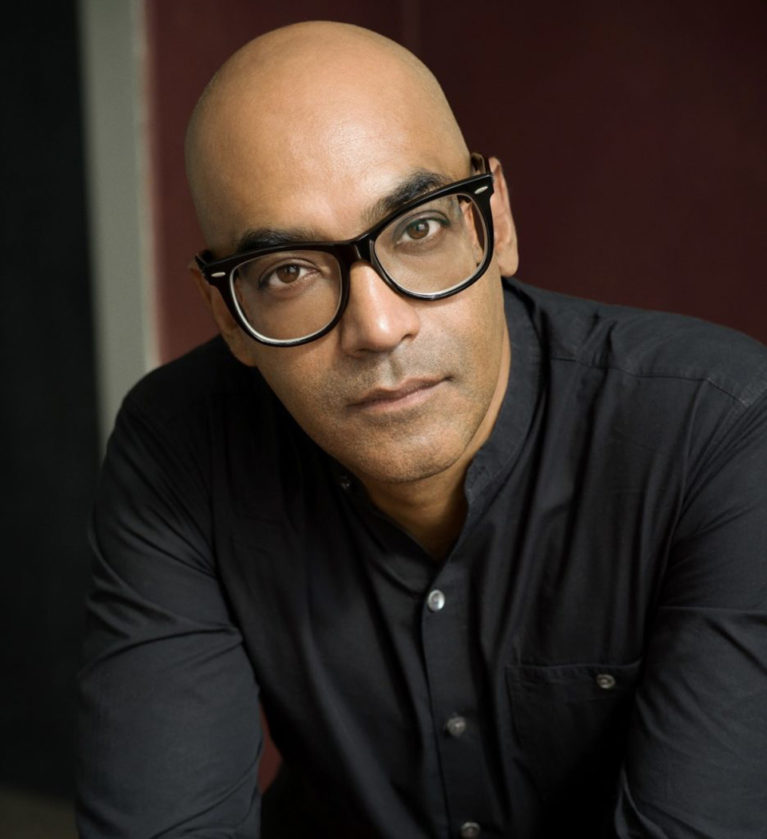

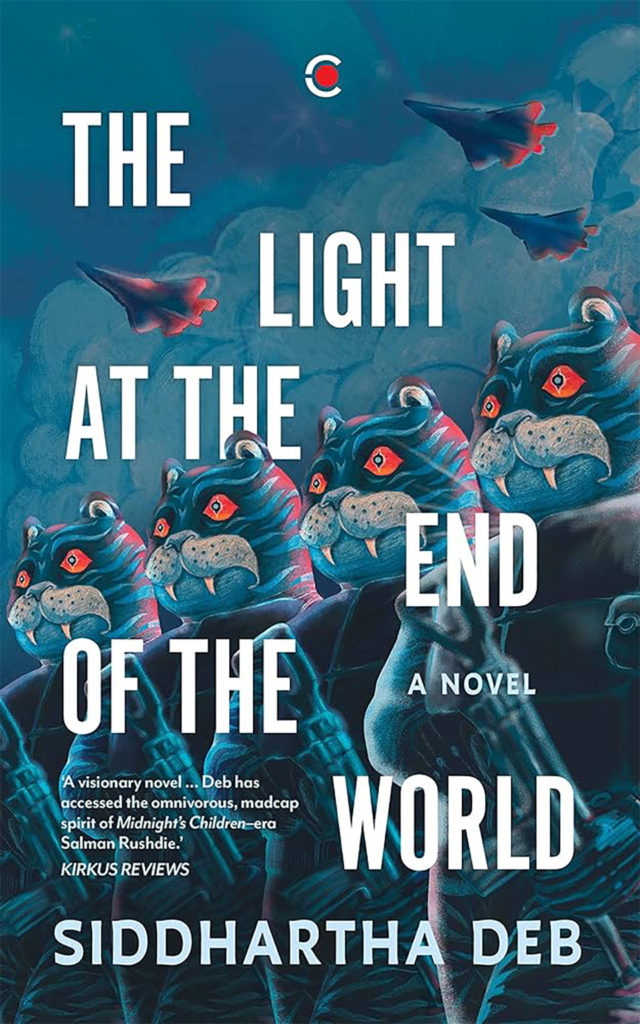

Four defining moments in India’s past and present weave together in Siddhartha Deb’s The Light at the End of the World, an expansive, sweeping novel of fever dreams and buried truths. Real-world history bleeds into the speculative as we follow its characters back in time. In a near-future apocalyptic Delhi, Bibi, a former journalist, tracks a history of conspiracies that involve detention centres, alien wrecks, and human experimentation. In 1984 Bhopal, an assassin follows his victim across Union Carbide’s factory grounds, employed by a mysterious patron. In 1947 Calcutta, a veterinary student believes he is building a machine that can bring hope to his city. And in the Himalayas in 1859, a troop of British soldiers on the heels of an anti-colonial rebel discover strangeness beyond their wildest imagination.

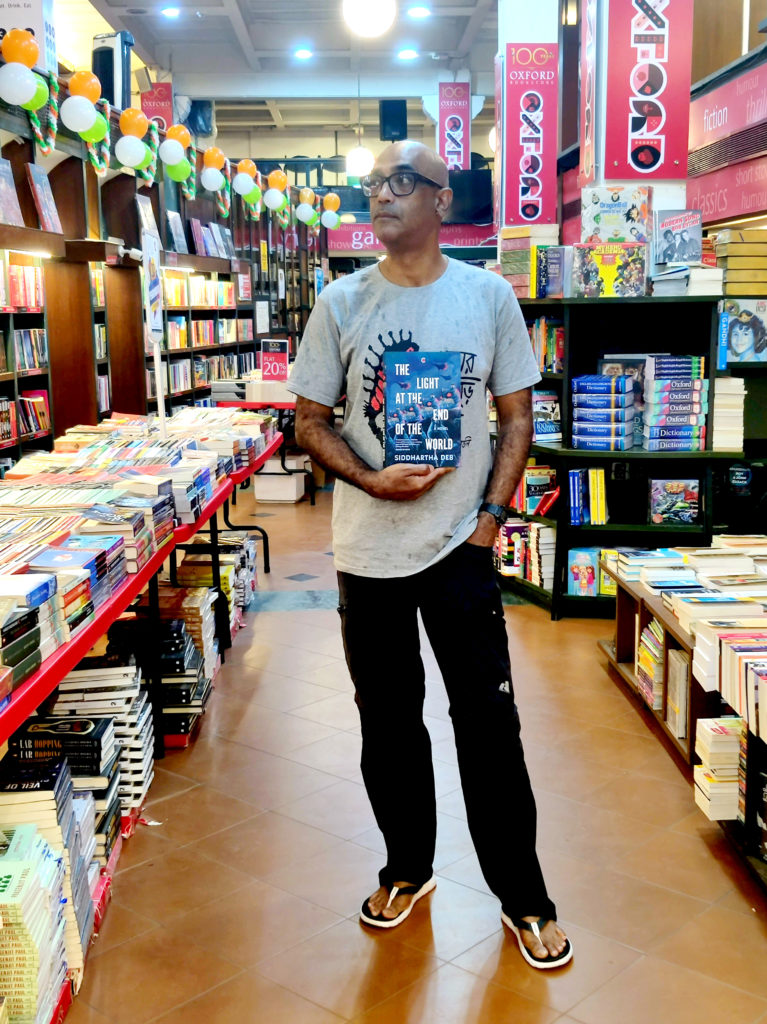

In The Light at the End of the World, individuals come up against the weight of oppressive regimes and organisations. Playing with genre boundaries, and peppered with motifs that reappear like recurring dreams, this is a vivid, unforgettable read; a reminder both of how our modern world got to where it is, and of what the novel itself can do. Siddhartha Deb spoke to Helter Skelter about structuring his novel, the ethics of writing about real-world incidents, and how the fantastic can illuminate the real.

When writing the novel, did you begin with a section in particular, or did you conceptualise the whole narrative right from the start?

I didn’t conceptualise the whole book in the beginning. It started with the Calcutta section, and with the main character, Das, failing to pass his riding test. And then the other novellas showed up. At a certain point, it became clear to me that I wanted to put the whole thing into a larger book, and that they had to connect in some way. I did connect them—it’s very, very light, it’s very below the surface. I think a lot of reviewers have really struggled with that. The connections are there, but they’re kind of hidden.

It started with the Calcutta section. I knew it was set in the Partition and yet it was not a “typical” Partition novella. It wasn’t going to be realist completely—even though it was about the violence and the famine, there were these slightly speculative elements in it. I knew that was going to be a thread in all the stories, that they were going to start quite realistically, in very grounded historical moments, and then move into a speculative direction.

I’m glad you brought up the hidden connections, because there are so many of them—it made the novel feel like a sort of puzzle box. There are thematic relationships between the novellas, but there are also lots of little details that connect them. How did you go about weaving the stories together in these subtle ways?

It took a long time to write, but I think that’s the pleasure of a big novel, that you get the time to go back and rethink the connections. It was meant to be quite a rich novel. I like the fact that you said “puzzle”—I think one of the playful elements behind it was the puzzle aspect of it. There is the puzzle poem that operates in the Bibi section, but it’s also true of how all the different pieces play with each other, fit together. At a certain point it became clear to me that the Agha Shahid Ali poem that I use [‘I Dream It Is Afternoon When I Return to Delhi’] was going to be a connecting puzzle piece.

It was part of the joy of discovery, of the book, of the stories, of the characters, of the times, and what they’re doing. A lot of the time, I had to wait for the connections to come to me. That is the pleasure of writing a big novel over a long period of time. People talk a lot about the difficulties, which exist, but one of the joys is these connections need time to emerge from the subconscious into the narrative. There is a kind of tradition of this kind of playful fiction outside the Anglo-American tradition. I feel a bit sad that Indian writing in English seems to be really dominated by the very narrow Anglo-American tradition. There is the very playful Cortazar’s Hopscotch, OuLiPo, Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveller. You’re playing with stories—that’s one of the joys of storytelling!

How long did it take you to write the book?

It was basically written over seven summers, so people say seven years, but it’s not like I was writing for 12 months [of the year]. I have a full-time teaching job, I was doing a lot of journalism, I have life to live! So it was mostly written when I was not teaching.

I write and revise constantly, so I would finish the draft of one of the novellas, and then I would be polishing and revising that while beginning the next one. It’s like you’re stacking boxes, building a tower. And then you go back again, because you’re looking for the connections.

A lot of your book takes from real-world historical incidents. How did you approach writing these alternate histories?

For me, alternate histories are very appealing, as a reader and as a writer, because I think it allows us to do things with history, with reality, that we can’t do strictly in realism. It also allows us a certain kind of freedom that we may not feel in a certain kind of political moment, with authoritarianism and climate change and violence. Even in our everyday lives, you can feel very constricted, you can feel very trapped. So alternate history is a way of breaking through that as a writer—exploding that, and looking for possibilities.

“Alternative histories allow us a certain kind of freedom that we may not feel in a certain kind of political moment, with authoritarianism and climate change and violence.”

You also draw inspiration from other places, like with the book Roadside Picnic, which features a forbidden area called the Zone that is populated with strange artefacts and has strange effects on the people who encounter it. How did that influence find a place in your novel?

It was the film first, actually—it was Tarkovsky’s Stalker [which was adapted from Roadside Picnic]. Twenty years ago, maybe, I was watching Stalker, and within twenty minutes I said, “This is about Bhopal. This is about Union Carbide.” I’d been there as a reporter on the 30th anniversary, I had walked around, and I said, “This is like the Union Carbide factory grounds.” Clearly, that stayed in my head for more than a decade. The idea of the Zone became a very compelling motif. It’s there in the Bhopal section, ‘Claustropolis’, but it also shows up in ‘The Line of Faith’, the 1859 section. It was almost like a virus of stories and motifs replicating itself. It was happening to me—I was following it as a writer. Not to give away too much to the reader, but that is one of the connecting threads through all the novellas—what is happening with the Zone, and what is happening with the supposedly “alien” artefacts found in the subcontinent.

How did you approach fictionalising these real incidents without trivialising them, and staying true to the tragedy of the incidents?

I did question the ethics of fictionalising 1984. Should I do it? Is it right to put a speculative aspect to something that is very real and horrifying enough in its reality? And then I thought, I’ve written about it in nonfiction, I’ve written about it in completely realist, empirical detail. It’s there in the opening of The Beautiful and the Damned, where I’m meeting Abdul Jabbar and the other activists. But nobody reads it! It’s completely forgotten. It’s still forgotten.

There is no HBO show called Bhopal. There will never be an HBO show called Bhopal. If you google ‘Bhopal.com’, the first website you will get is Dow Chemical’s website, because they have bought the domain name. Even in India, people don’t know about it—people don’t care about it. There was a kind of anger in me. Why was it forgotten? Are there fifteen books and movies on Bhopal? Why not? Why are we so bad at understanding our own history? And does that have something to do with what is going on in the present?

“There is no HBO show called ‘Bhopal’. There will never be an HBO show called ‘Bhopal’.”

So I gave myself permission. I said, I have written about it in nonfiction. No one gives a damn about it. It’s not that long ago! And yet everybody knows Chernobyl and Fukushima. So I gave myself permission. I am trying to bring it out into the world. I’m trying to make it not-forgotten. And if I have to use the speculative and the fictional aspect to do it, it is allowed.

I do remember one conversation I had with Abdul Jabbar before he died. He said, “Aap kya likh rahe ab?” [“What are you writing now?”] I told Jabbar a rambling version of this story I’m writing. I thought he’d be quite critical, because he’s an activist—he’d given his entire life to this. He said, “No, ye bahut achcha kahaani hai, aap likhiye” [“This is a very good story, you write it”]. That made me very happy.

Some of it came out of the reporting. Everybody in Bhopal said it was a conspiracy. The rich people would say it was a conspiracy by the poor and by Muslims, because this happened in the Old City, where there’s a large number of Muslim people. A lot of the people who died were very poor—Hindu and Muslim both, but they were very poor. Union Carbide itself said it was a conspiracy, which I have researched as a journalist and which I inserted into fiction—they first said it was done by “Sikh terrorists”, quote unquote, and next they said it was the workers. This is all documented. The poor people who had suffered also said it was a conspiracy, but they said it was done deliberately, as an experiment by the Americans. So I thought, what if I were to write a novella where it is maybe an experiment, and maybe both by the Indian and American governments? Why not? So that’s how reality bleeds into fiction.

When the [COVID-19] pandemic happened in India, and there were these scenes of mass exodus from cities forced upon people by the government, it brought to memory both the Partition and Bhopal, which are both in my novel. I think there is a way in which we compulsively repeat certain tragedies, certain kinds of violence. I think the novel is trying to grapple with that, by putting them in conversation with each other.

How did it feel to have the book released post-COVID?

That was a bit strange, because I had just finished it in February 2020, before COVID happened. And it was such a terrible idea—I didn’t know that in March, the next month, there would be an entire year to sit at home and work on the book!

There is a virus in the book that was written before COVID-19—what they call the China flu—and there are these masks that people wear in Delhi. So it was very creepy to see COVID showing up in reality, after I’d written about something like COVID in the novel. It was very creepy, similarly, to have the novel come out in New York this June. People were saying they were triggered by the descriptions of the air pollution in Delhi because the sky was yellow from the pollution, from the forest fires. It’s very eerie, but that is in some sense what the novel is also deliberately trying to look at. It’s trying to look at the eerie and the weird, which are deliberate words that I deliberately use. What seems fantastic is real, and what is real seems fantastic. To me, in today’s India, the kind of violence against minorities we have is real, but it seems fantastic. Climate change is real, but it seems fantastic. COVID is real, but it seems fantastic. That is one of the things that the novel is playing with—blurring the lines between the real and the speculative.

“I think there is a way in which we compulsively repeat certain tragedies, certain kinds of violence. I think the novel is trying to grapple with that, by putting them in conversation with each other.”

I’m actually curious what you think of genre, because I’ve seen your novel described as magic realism and I’m not sure I agree with that. I’d describe it more as weird fiction—it reminded me of people like China Mieville, Jeff VanderMeer, David Lynch.

You’re absolutely right, that’s what this book is influenced by in many ways. They are interested in blurring the lines between the real and the fantastic, in order to get at the real. In that sense they are a continuation of the surrealists. The novel is completely in conversation with that.

I think that people think about novels in this really boring way that’s all about families, and one of the things the novel is not about is “the Indian family”. I have written about it myself, but with this book I wanted to get away from that. I loved this moment [from the book tour] in Calcutta, when Sandip Roy, the writer, was interviewing me. He said, “Your characters dream of each other.” I said yes, they do! It’s not a logical connection, but it is one of the connections that the novel is interested in. They don’t know each other, they’re not connected by family, they are across different times and places, but they do dream of each other. And that is what I mean by the weird that I am interested in.

It is very much a very productive strand of writing, particularly in thinking about today’s political violence and climate change. Amitav Ghosh has written about this, that the realist novel is poorly equipped, in some ways, to deal with the fantastic nature of climate change or COVID or mass violence. So genre, for me, is a very productive way to look at reality. The weird, the speculative, the counterfactual, the alternate history, all these are very much in the novel.

Sometimes it’s a little bit sad that I think older people—people of my generation—don’t see it as serious literature. They say, “There’s a gangster in the novel, there’s a crime plot, there’s a ghost, so it can’t really be serious literature.” It seems so disconnected, both from a lot of the writing [mentioned before] but also our folk stories—they are filled with aspects of the weird and the speculative! There is very much the influence of reading—I love China Mieville, I loved the new Jeff VanderMeer novel, and David Lynch is a huge influence on me. But there’s also the ghost stories that I grew up with, in the Northeast and Bengal, which are really ways of talking about the famine, and talking about colonialism. They seem to be children’s stories, but then you think about it—why are all the villages empty in these stories? What has happened to all these people? It stays with you. You realise they’re basically talking about the famine, where millions of people died. It’s there in folk literature, in folk songs, and it’s also there in the genre fiction. I think these are both very alive influences. I love them as a reader, and so as a writer I wanted to do a book that would be as much fun.

“Genre, for me, is a very productive way to look at reality. The weird, the speculative, the counterfactual, the alternate history, all these are very much in the novel.”

One of the connections that shows up through your book is a kind of alive architecture. Characters often find themselves in physical spaces that appear to be constantly moving, bewildering, and hard to navigate. I was wondering how you like to approach physical space in your writing.

Physical spaces are very interesting to me because they are tremendously oppressive, especially under modernity and colonialism. And this continues today: if you think about the kind of “re-building” that is happening in India, and how it is meant to oppress, to make you feel bad. It’s not even just about India—if you look at airports nowadays, they are very, very disturbing places. They want to make you shop. There’s this anxiety about the security lines. Spaces are connected to modernity, and they have been connected to the novel, to the film, to psychoanalysis, which are also modern ways of responding to space.

I think one of the connecting threads in the novel is that there is an oppressive institutional space—a hospital, or a palace, or a factory, or a detention centre. In a way, they kind of bleed into each other—they are kind of the same place in different places in time. If you go into a hospital, even a modern hospital, they are just such disturbing places. If you had decided to make people as anxious and as unhappy as possible, you could not have chosen a better space for this. It is producing sadness, and anxiety, and grief. So I’m very interested in architecture, and the novel is trying to grapple with that: what happens to the human soul, the human body, in these spaces?

“I teach fiction, and sometimes a student says “this is so difficult”, and I say that’s totally okay, but that’s not a reason not to read it.”

Another physical space that recurs through your novel is the museum. In each novella, a character encounters some kind of museum or collection. I think Bibi describes the museum as a space where “separate streams of time have collided”. I was wondering what the idea of the museum means to you.

It’s interesting how it started showing up in a lot of the novellas. In Bhopal, it shows up as the outdoor museum, what he calls the National Collection of Man. Then there is the Dolls Museum in Delhi, which is a really fantastic, weird space—and it exists in reality! And there’s the Calcutta museum, which plays quite a bit of a role in the ‘Paranoir’ section.

I think collecting is a colonial obsession. It’s a way of showing your dominion over the world. The Western colonial powers did it initially, but even in the postcolonial it has continued. It’s a way of showing your domination over everything—over landscape, over people, over animals, over lives. And so they become these very strange spaces. They are supposedly built on rationality, or science, or art—for good things—but they become very uncanny spaces, because if you think about it, what does it mean to just remove something from its context and just put it there? It’s plunder! It’s about conquest. Museums are built off stolen objects. Supposedly, you go there and then get educated. And it’s really bizarre, because there are these different conflicting modes of looking at the world that get crystallised in a museum. The Koh-i-Noor diamond, why does it sit on the Queen or King of England? Even in the postcolonial project, the Indian project, like the National Collection of Man, I find it quite strange that there is a Konyak Naga hut in Bhopal. Bhopal has its own rich indigenous people and tradition. It’s this obsession of collecting things from within our boundaries. They’re very uncanny spaces to me, where things can happen beyond what is intended, which is supposedly education.

In the novel, some of the objects are almost on the verge of coming alive. They’re not just objects to be collected. I’m interested in that uncanny, speculative element. The horror genre uses this all the time—you bring a mummy to the museum, and then the mummy comes alive! But I’m trying to take it a little more seriously and with more empathy. They are not monsters to be conquered. They have already been conquered. The idea of the monster or the “alien” or the “other” is different for me in the novel. In Lovecraft, the alien is the source of cosmic horror. But what if the alien is the source of cosmic hope?

I wonder what you think about novels that are challenging to the reader. Your novel doesn’t give away all the answers, and it doesn’t try to explain everything. How do you feel about novels that are ‘difficult’?

I didn’t realise my novel would be so challenging for some readers! I teach fiction, and sometimes a student says “this is so difficult”, and I say that’s totally okay, but that’s not a reason not to read it. It might be interesting even if it’s difficult. I think there’s a kind of Netflixisation of novels that has happened. I quite like cheesy stuff—I love Money Heist and Squid Game, I’m a great fan of these things, But recently, I’ve noticed, when I look at Netflix, it doesn’t matter whether I’m seeing a trailer for something set in Korea, or India, or the U.S.—they all look the same. The narrative moves at the same pace, the filming is the same; even though the characters are ethnically different, the stories are the same. I think there’s a kind of homogenisation of the novel as well, and I find that very disturbing. I think stories are meant to be different and strange and sometimes not make sense, but also be fun and do new things. I’m always puzzled by people who say “this doesn’t make sense”, because things that don’t make sense can also be very interesting!

When I was meeting readers and booksellers, I felt very enthusiastic and rejuvenated; I felt quite hopeful. On the one hand there is this real, closed corporate culture; on the other hand, booksellers and readers are imaginative, innovative, and adventurous. To say something is difficult is also to say it’s an adventure. I do sometimes think readers are more adventurous than publishers give them credit for.

“Books about America can be about the world. Why can’t a book about India be about the world?”

Have you seen a difference in the way U.S. and Indian readers have received your book?

There is a difference between U.S. reviewers and Indian reviewers, and between U.S. readers and Indian readers. U.S. reviewers have been very positive—they’ve been puzzled, but they’ve been positive. They’re also connecting it with other strands—Pynchon, Cormac McCarthy, and Octavia Butler—other literary fiction that also plays with genre. Sometimes Indian reviewers are very caught up with the idea of India. It is about India, but it is also about the world, which is part of the project of the novel. Books about America can be about the world. Why can’t a book about India be about the world? All readers create their own book, because reading is a creative act, so every reader is reading a slightly different novel. That’s true of all really good books. I think it’s only true of the really dull books that everybody is reading the same novel. The U.S. readers seem more sensitive to the climate change aspects, and the fantastic elements, which is not an unproductive way of reading. Sometimes for Indians, it’s too close to what is happening—which it is. People say, “There’s a moon landing in your novel!” And I say, no, there’s no moon landing. There’s a Mars landing in my novel—and it’s a piloted Mars mission. Reality hasn’t caught up yet!