In Praveena Shivram’s debut novel, Karuppu, the land of the dead is a shifting, moving spiral, presided over by Yama, lord of the dead. But Yama is missing, and in his absence, chaos reigns. A prophecy comes to light, and two children from vastly different worlds become caught up in it—Karuthamma, a young girl who grew up on earth, and Sigappi, an intersex child who lives in the underworld. Karuppu is a whirlwind of memories and dreams, where the past and the present interweave and boundaries are porous and malleable. At the centre of it all is the unforgettable figure of Karuppu.

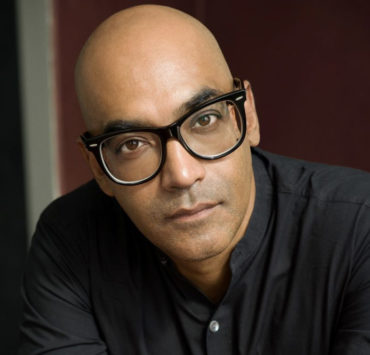

Taking inspiration from characters from mythology, Praveena Shivram builds an entirely original world in Karuppu, a fantasy novel marked by its fluidity. In conversation with Helter Skelter, she speaks about approaching stories and characters on their own terms, using fantasy and myth to reflect human relationships, and the importance of not succumbing to a binary mode of thinking.

I’m curious about how you see the audience of the novel, because this is published in Zubaan’s young adult imprint. Is that something you thought about when you wrote it?

I never wrote it as young adult at all. The publishers took a call on marketing this as a young adult book, partly because the character is fourteen years old. But also, Urvashi [Butalia, of Zubaan Books] is somebody who redefines the publishing space so much, and Zubaan as a publishing house really works hard to not succumb to market trends. They really look at the list they’re creating for, say, ten years down the line. How is it going to change the literary landscape? Who are the people who should be published? I love the fact that Zubaan is constantly asking these questions, constantly looking at what is a “bestseller”. Do you look at a bestseller as something that’s happening now, or is it a bestseller if it stays for twenty years? Very deep and insightful questions. It was very heartwarming to be in that space, and really feels good that I’m one of their writers. It’s nice to be part of that process, even in the smallest way possible.

Urvashi has always said that the best YA books are those that straddle both the adult and the YA space. The lines blur. It doesn’t have to be only young adults reading it—even adults should be able to read it, and vice versa. And that’s probably why they pegged it as YA. But when I wrote it, I didn’t have a fourteen-year-old in mind.

It was really nice to read a YA book that doesn’t feel like it’s talking down to its audience.

That’s true, because YA should not be doing that. I think when you start writing a story, if you become very conscious of your audience, you will compromise on the story. That’s not something you should do. I don’t think you should even worry about which market is going to read your book when you’re writing it. I think that comes much later, and there are other things that play into those decisions. You can’t really cater to that. You cater only to the story.

“I don’t think you should even worry about which market is going to read your book when you’re writing it. You can’t really cater to that. You cater only to the story.”

The blurb of the book specifies that this is not a retelling of Indian mythology, but a reimagining. How did you approach that? How did you decide what to take in and what to make up?

I never set out to retell a mythological story. It started with Karuppu. When I was young, there was this serial on Doordarshan, before the time of cable. It was called Vidathu Karuppu. It was this horror series, which talked about supernatural things, like being possessed… so that ‘Karuppu’ word came to me from there. And it was called Marmadesam, the world of secrets. That’s the title of the serial. So that was my starting point.

And because Karuppu belonged to the world of the dead, Yama came in. That was the natural transition for me. When I read up, I found out that one of the Vedas has this story of Yama and Yami, which says that they were the first mortals on earth. I picked that up from there, and the rest of it is just totally made up. There is no mythological proof to any of this.

I call it a reimagining, not a retelling, because when you look at it from a character’s perspective—if I just look at Yama as a character, and I go into an emotional space of Yama, then automatically I will stay true to that emotional graph. And when you stay true to the emotional graph, you cannot stay true to the mythological part of the story. It has to be one or the other. If I was going to retell a myth, I would not have looked at the emotional graph at all. But because this was a deeply emotional story, with everyone being impacted by each other, everyone completely caught up in this web of lies. The whole space was so human, really, that it couldn’t have stayed true to a mythological retelling. That is why I said it was a reimagining.

What possibilities did you see in the space of mythology that drew you to it?

I wasn’t ever really drawn to the mythology of it at all—I was only interested to look at Yama as a character. Then I wondered, what happens to Yami? Nobody talks about her after that. What would she have gone through as the twin who’s left behind? Everything was really connected to really human emotions and very human frailties. How does that impact a person?

Even the whole idea of one not being separated from the other is a representation of human relationships; the whole power dynamic between people. How do I look at the other? How does the other look at me? How much power do I have over the other? How much power does that person have over me? How much of it is circumstantial, how much of it is manipulation? So many things happen in that space. Yama and Yami gave me the perfect rich fertile ground on which I could talk about all of this.

I was conscious of one thing: all of my stories, any of my fiction, somehow become very Tamil in nature. My characters are Tamil, my world is very Tamil. I don’t feel the need to explain anything to anyone—which is why I don’t explain the words either in the book. I don’t feel the need to explain how to pronounce Chezhian, you pronounce it however you want. Or even Karuppu. I think that’s something that comes into whatever I write. And I loved how Nitya, who’s the designer at Zubaan, even did the chapter heads with Tamil words. It’s very beautifully done.

There’s a lot of fluidity in your book—on multiple levels, between characters, bodies, gender, light and dark, right and wrong, past and present. What drew you to write such a non-black-and-white world?

I think it’s just how I look at life in general. If I don’t have fluid spaces between me and another solid body, then there is no flow of life. This fluidity has to be there for my solidity to exist, and the other way around. They have to complement each other at all times. The format of each character telling the story helped me keep it fluid—you have specific perspectives and specific voices telling you the same story but in different ways, because they are all each flowing in a different way. Every character, every emotion, every interaction remains in that fluid space.

“All of my stories somehow become very Tamil in nature. My characters are Tamil, my world is very Tamil. I don’t feel the need to explain anything to anyone.”

This was not done consciously. It’s how I look at life in general, and that seeped into the story itself. It is obviously meant to be in the grey space, because I’m dealing with the world of the dead. Ironically it’s called Karuppu, and the second book was going to be called Sigappan. I was trying to challenge this black-and-white version of how you look at the world, and how that actually doesn’t exist. Everything exists only in the grey space.

I think it’s also part of any story that I write. How I look at characters is also how I surrender to them. In surrendering to them, I also surrender to their fluidity, and allow myself to flow into that space. If I don’t do that, I will not be able to understand or hear or see or smell those characters, and if I can’t hear, see, smell them, I can’t write them. There is this almost symbiotic relationship that I have with the story, with the characters, because I do see them as living beings. I don’t discount it as “fiction”. It’s not. It’s a lot to do with life. I define fiction as another way to look at reality. It does not make it any less real than what I consider reality right now. Just because I’m here in the physical does not discount Karuppu in the physical. I’m not a part of that world. I got the gift to talk about that world, but that’s it. I can’t enter that space, as much as Karuppu can’t enter my space.

It’s so interesting that these weren’t conscious choices, because your examination of boundaries and boundary-crossing and binaries is there at every level in Karuppu, especially with gender, like with Sigappi.

There’s so much talk about appropriation—“you can’t talk about something if you haven’t lived it”—and I don’t necessarily agree with it. Maybe that’s because I look at my characters’ world and that space very differently. I actually erase myself and go into that world and then write. So there is no ‘Pra’ really existing at that moment, there’s only the character. There’s only Sigappi at that moment, not Praveena’s version of what Sigappi is.

I did talk a lot about it with my publisher, because there were some lines that we thought wouldn’t be politically correct, and maybe people would misinterpret or misunderstand it. I don’t want to be politically correct, because in Sigappi’s world, this “political correctness” does not exist. It is my world’s existence and not hers. It was a risk I was happy to take, because I don’t want to be untrue to that space, or to her. I do want that confusion that she went through to be there, because it’s natural for that confusion to be there. There is no vocabulary for her to talk about it, there is no agency for her to talk about it.

What drew you to write an intersex character specifically?

I think that was again dependent on the story. I was imagining if this were to happen, in a world where constructs of love and physical touch and desire and lust don’t exist, what could the baby possibly be? Who could the baby possibly be? Maybe it could be an intersex child, because in the world of the gods, you do have these intersex bodies that exist. It’s not a spectacle, it’s not an anomaly, like how it’s become a spectacle for us in this world. It also served the central plot very well, because you know a girl has to be there, but you don’t know which girl—because they don’t even accept this one as a girl. And that is not because of the politics of our world, but the politics of their world, where they don’t want this prophecy to be on her. Here the story is actually of acceptance. If you look at it from our lens, then your understanding is going to be very warped. But if you remove that lens and look at it just in that world, then it’s quite natural that all of this would happen.

Again, I had to do a lot of reading up, I spoke to a lot of people. I think my only nod to it from this world to that world was the chapter where she says “You better change it to Sigappi right now” [this is in response to the chapter being titled “Sigappan”, the male name she does not choose to go by]. That was my only way to say, okay, I’m acknowledging it, but that’s it. After that, Praveena is gone. Then it’s just the story.

“How I look at characters is also how I surrender to them. In surrendering to them, I also surrender to their fluidity, and allow myself to flow into that space.”

I’m interested in your style of writing, in that everyone is speaking very casually, and sometimes to the reader, like in that moment you mentioned. For me, that brought up the idea of oral traditions—there’s all these very natural digressions in the characters’ perspectives.

The choice to have it in first-person was from the beginning. First-person allows me to rely more on the character and less on the narrator. If there were digressions, I could actually use that to my advantage. Each one was telling the story a certain way, so by the end of it you’re wondering, which version should I actually look at? Which is the thread that I should follow? Whose version is the real version? All those things come into play, which again serves this whole idea of fluidity.

When you’re actually living life, you can say I’ll look at something a certain way and that is true to me. But somebody else may look at something differently and it may not be the same. I’m not talking about a truth, I’m just talking about the way I look at that one truth— how I look at it is what matters. It’s almost like that Kurosawa movie, Rashomon. There’s also a Wilkie Collins book called The Moonstone, which is the first time I came across the idea of a single story, but where everyone has different perspectives and you have no idea which one it is, finally. So that is an interesting device for me when I’m telling this particular story, because everything is so different.

I was wondering, how do I access that world? Do I access it as somebody sitting on the outside, and having a character walk me through it? Or can I just not worry so much about “am I telling this story, am I the writer, am I the one with the craft”? Can I put that aside, and then just simply enter the world through the characters? Enter it in all honesty and with complete trust that they will see it through, or I’ll be able to see it through them? That was something I found interesting and it helped me tell the story, because I allowed them to say it. It was not so much me. I know it’s me, but it’s not.

“There are these moments of sudden objectivity, where you can put yourself outside, look at yourself, and then come back. I really wanted to mimic that in some sense, where I’ve pulled you so deep into a story and then I take you out again.”

Your book has such a variety and range of different spaces you draw quotes and references from for your epigraphs. There’s also these song interludes called ‘Karma Chameleon’, talking about the story itself. How did you decide to include these quotes and interludes? What drew you to bring quotes from, for example, Simon & Garfunkel and Orhan Pamuk together in the book?

I wanted those interludes and little quotes over there to suspend that world for a bit, and still be able to look at it from the outside. This play of in and out is also true of how you live. You’re constantly looking at yourself from the outside, and you’re living it. You have these moments when you’re in the middle of an argument and you just feel like you’re watching yourself arguing and thinking “What am I doing?” There are these moments of sudden objectivity, where you can put yourself outside, look at yourself, and then come back. I really wanted to mimic that in some sense, where I’ve pulled you so deep into a story and then I take you out again. So this whole dance of the inside and the outside was really what those quotes and the ‘Karma Chameleon’ interludes are doing.

Those are popular culture references: ‘Karma Chameleon’, Simon & Garfunkel, Orhan Pamuk, Raúl Zurita, all of them contemporary and belonging to this world, which adds one more layer. I’m constantly making you aware that you don’t belong to that world, but you’re getting a moment to see what it is like. But you have to come out. There’s no way that you can live there.

How would you like people to approach your book?

I hope that all readers read it with kindness, and open-mindedness, and not get very caught up in the politics of our world—with willing suspension of disbelief, like Samuel Taylor Coleridge said. If you can do that and read the book, that would be the best way to experience Karuppu.