What does it mean to be brown—a many-hued, many-headed, living, breathing idea? What is this word useful for?

As an identity, it’s often used interchangeably with ‘South Asian’—a polysemic term which gained currency as a category of division after the establishment of area studies departments in the U.S. In a 2014 issue of SAMAJ, Aminah Mohammad-Arif describes the connotations peculiar to the term ‘South Asia’: a region where multiple religions interact, thus challenging the idea of (homogenous) culture as specific to a region; the legacy of British colonisation; the several partitions in the region and their faultlines; the outsize real estate India occupies in the popular imagination of South Asia, seen literally in its other analogue, “the (Indian) subcontinent”.

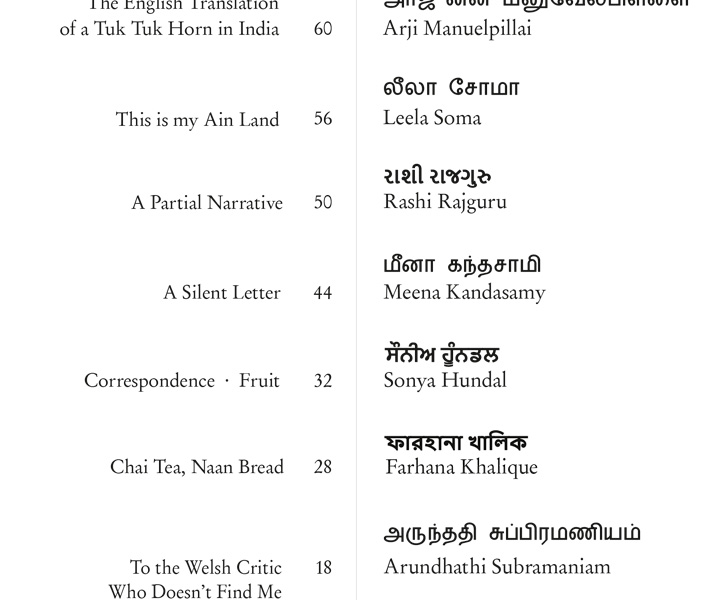

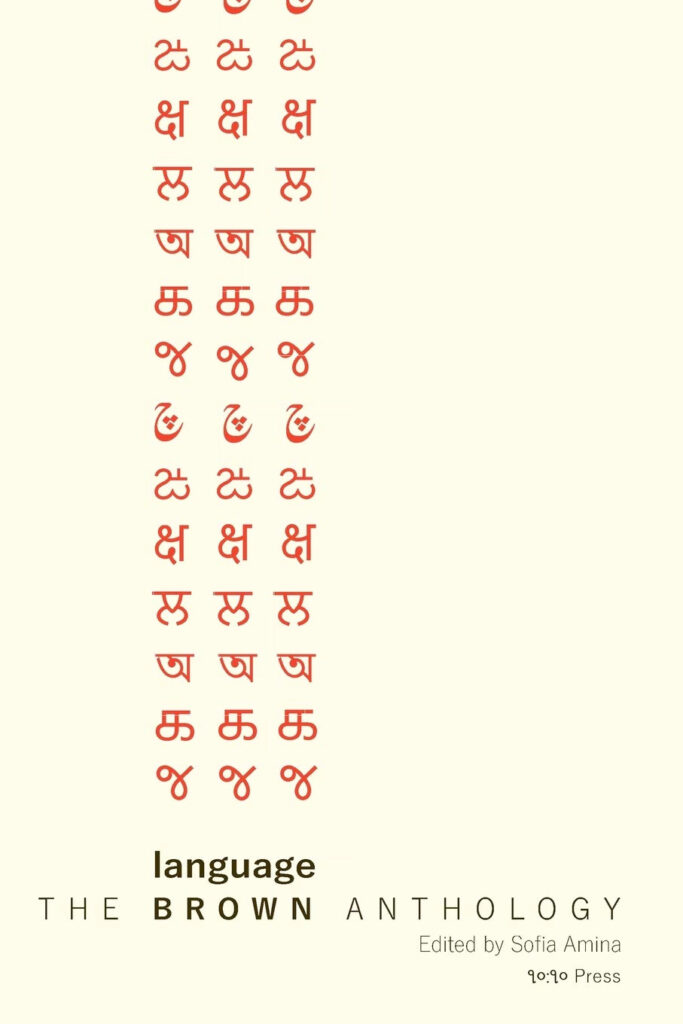

The Brown Anthology: Language is the first release from artist-owned ૧૦:૧૦ Press. Publisher Sofia Hafeji declares it to be about “historical present and future Brown” without the “need or prerequisite to explain, justify, or create art to suit the perception of Brown”. This editorial defiance permeates the aesthetics of the book from its emphasis on vernacular-first names and bottom-up table of contents to the unusually lopsided poetry-heavy composition.

Two poems from Arundhati Subramaniam set the tone. The first is perhaps the clenched teeth of the anthology: “Pity me, sweating, rancid, on the other side of the counter,” she writes. “Stamp my papers, lease me a new anxiety, grant me a visa…” summons the new notice from I.C.E. The second poem is softer. When the poet was a child, she ate mud.

Like the wisdom of eating mud, ‘brown’ is a contested word. It’s become cliché for people living in South Asia to drag the diaspora for their reliance on mangoes, mothers, and Partition in their writing, while papering over less pleasing inheritances like caste and Islamophobia that they also carry across shores. Could ‘brown’ be, instead, a commitment to collective politics, beyond aesthetic?

You discover you are brown only in contrast. People who have only lived here cannot comprehend the rootlessness of being brown in a sea of chalk, the loud voice disrupting the politeness of a checkout line.

Readers will find different pieces in this anthology fruitful. For me it was the sweetness of Farhana Khalique’s lines that called out to me, the Sylheti in my own blood charmed by her sifting syllables and Sana Soor (which I’d call chana choor in my tongue). This, I think, is close to the secret hope I nurse in reading this anthology. Is it possible to look for resonances in our separate histories without declaring them the same and flattening complexities? It is not difficult to imagine her parents saying of green tea, “Etha Saa nai, etha faani/ That’s not tea, that’s water”.

K. Devan’s essay Lost in a Jangal had me weeping, caught off-guard past my bedtime. Devan describes the ‘word-salad’ of their grandmother progressing through dementia. Standard practice is to review in universals with a touch of authority, but this collection has me thinking through the ‘I’. Our relationships to the brown languages we know and live in, and the ones that slip through our grasp are so personal. What this anthology stirs up is personal.

Devan’s essay resurrects my grandfather—over six-feet tall, sitting at the dining table in lamplight, counting “one, two, three, four” over and over again on his fingers because he had forgotten what “five” was. Long after he forgot who we were, and after we set bars on the balcony, he continued counting one to four, long after he stopped saying anything else. Why English and not Bangla? Who knows the reasons language stays with us?

And this sets on the table the question of why this anthology focuses on language.

The publishing standard internationally is white—anything else demands explanation, flattening exoticisation, italics. The anthology subverts this tradition, and in that regard it succeeds. We need more. People who write the world decide what it will mean.

In her story, Sonya Hundal describes shahtoot as mulberries and can’t help but wonder if that’s what they call it in Punjab. Her tactile descriptions of the juice from the fruit staining a lime-green dress, “roti so full of bran it only makes biscuits”, “so white it makes tough rounds” from her series of epistolary stories in which a soldier in France saying “I dream of sugar cane” shows us the heart of brown. Food. And language.

In the same issue of SAMAJ, Sudipta Kaviraj notes the long temporal rhythms of material cultures. When away from the origin states and rigid borders, cultural commonality reasserts itself. Food “tends to seep out under the boundaries of states”, he writes. Language too.

Food and colour are prevalent through the pieces in the collection—mostly poems, alongside an essay and two short stories. How else do we remember and organise a language, a land in our mind but through its smell, its taste, its textures: the phulkari of Sonya Hundal’s short stories woven into a tradition of socioeconomic inequity, Amna Naeem’s poem Urdu translated into English writes of her grandmother as embodying Urdu, “wandering barefoot, wrapped in a black and white dupatta/ around my angled house at the 13th hour”, worrying that growing up will mean growing away.

Running through the collection is also this gulf that threatens to separate the writers from parents, grandparents, lovers, symbolised through language laying bare different ways of being. A single Meena Kandasamy poem halfway through the anthology lends a delicious thrill of recognition as she writes of “a tongue tied to its roots/ Untrained to let things slide”.

Rashi Rajguru’s reflection on her relationship with Gujarati as a British Indian is precise and beautiful. She writes: “I think about how strange it is that there is a no man’s land of untranslatability between us, how my Gujarati and their English will never meet in a state of pure transference.”

This sentiment bears resonances to Leela Soma’s poem: “not an Indian in India nor a Scot in Scotland, a new wean fae an Indian womb, nurtured rich in tartan air”, she writes in a hybrid vocabulary—not the derogatory hybrid of racism, but the hybrid as imagined by postcolonial theorists, talking back in their own tongue. Rukmini Bhaya Nair closes the anthology with two poems that demand rereading, particularly the serpentine Ode to our Languages winding through the A-Z of languages in the subcontinent.

The anthology is heavy on India although there are contributions from writers of Indo-Fijian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi backgrounds. Perhaps the books that follow in the series will people out the many meanings of brown.

Depending on the reader, the variety in the anthology may delight or disorient. To lurch from the energetic bursts of Arji Manuelpillai’s poem from a Tuk Tuk horn (frenetic, like you can feel the potholes and pedestrians in the way) to Mani Rao’s poems that read rather like riddle-like meditations (Pupa literally begins ‘“Dreamscrawler”) is an experience that—let’s not be cliché and call it uneven; let’s say it’s unexpected and one doesn’t know what to make of it at first encounter. But perhaps this too is part of the politics of defiance.

As a brown writer, here is a use of the word ‘brown’ to my mind. The publishing standard internationally is white—anything else demands explanation, flattening exoticisation, italics. The anthology subverts this tradition, and in that regard it succeeds. We need more. People who write the world decide what it will mean.

There is a Rumi poem that was diluted down in translation, stripped of Islamic connotation. “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there,” it goes.

Out beyond hackneyed phrases like “unity in diversity” there is the idea of cultural difference. This anthology makes me hope for this more sturdy kinship; solidarities that are built on recognising that our roots and futures are tangled up in each other across disjunctions and continuities. As Gwendolyn Brooks writes, “we are each other’s magnitude and bond”.

I think ૧૦:૧૦ Press takes us toward that field. You know how it goes. I’ll meet you there. (But hold the chaa please, I’m lactose intolerant.)