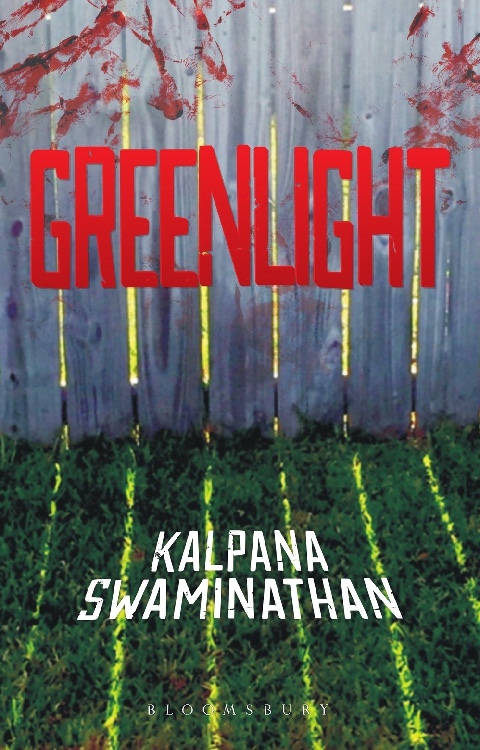

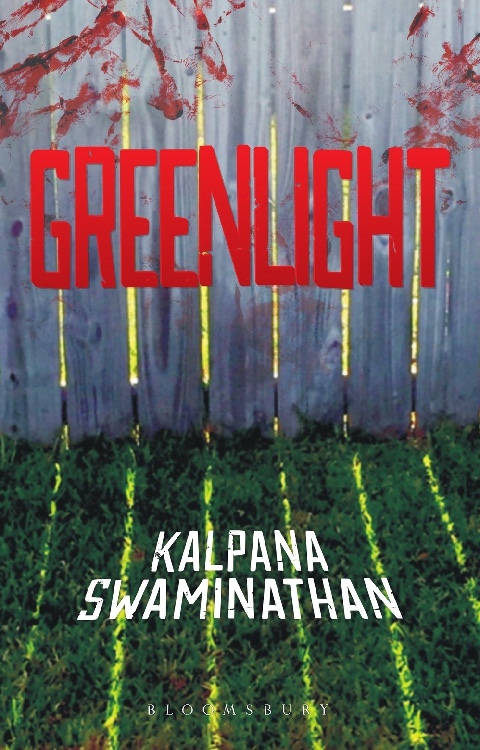

Greenlight, the sixth book in Kalpana Swaminathan’s acclaimed Lalli detective series, is not for the faint-hearted.

The plot is simple: young girls are picked up, and their mangled and mutilated bodies are returned. There is pressure on the police to bury the investigation, because politicians are involved. Since these children are from the Kandewadi slum, no one really cares for their safety or well-being. We meet the motley crew of characters; a retired detective, Lalli, in her 60s, who is the protagonist of our novel, her niece Sita (not Seeta, more on this later), police officer Savio, police surgeon Dr. Q, and Sita’s suitor (and pompous jerk), Arun. The relationships between the characters are a little difficult to understand in the first few pages, but the links become clearer as the novel progresses.

Greenlight by Kalpana Swaminathan (Purchase)

Greenlight by Kalpana Swaminathan (Purchase)After a heart-stopping start, the book slows down for the first 50 pages or so, but then becomes absolutely unputdownable. As fans of the series know, Lalli has shades of both Sherlock Holmes and Lisbeth Salander. She is also our (very realistic) superhero; aided by serendipity and helpful flunkies, extremely intelligent and daring, unafraid to take on the status quo, and ultimately singlehandedly solving her case. She interviews and investigates, pores over evidence, goes on late night drives to catch criminals, and trawls Twitter. She can be cold and calculating, but also shows unexpected humanity and tenderness. The beautiful thing about Lalli is that she is devoid of all glamour. She is an old retired woman, outspoken, single, has strained relationships, and is not the most charitable in her judgment of other people. But she is also competent and courageous, and passionate about her work. This is a grey character that you can’t help but root for, and therein lies the power of Swaminathan’s writing.

The story is written from Sita’s point of view, and vital characters in the book who help the investigation move forward are female. We meet a woman whose job is to dispose dead bodies, a constable, a truth-seeking journalist, high-society women who want to do something for women but are too disconnected to make a difference. We meet men of different shades. The slightly sexist but ultimately indispensable police crew, the too-good-to-be-true man who turns out to be a huge fraud, a mentally ill man masquerading as a professor, and the mentally ill man who might just be the cause of this whole mess. We meet young, vivacious, school-going children, some smart and alert, some easily lured, all extremely precocious. And then we meet the perpetrators. Their very real disconnect with those who are not as well off as them, their ‘boredom’ with a safe life, their desire to seek validation from a complete stranger online, their depravity and complete lack of humanity in cutting up children, is too real to turn away from. The book invests time in building its characters, gives some of them back stories, and does a good job of making them all seem like people we would know.

One of the most beautiful things about this book is that it lays bare the great inequalities of wealth in our very own Mumbai, in a way that is difficult to ignore. There is a stark contrast between life and lifestyle in the high-rises and slums, separated only by a wall, interdependent, yet worlds apart. There are the high-society people, who see slum dwellers as little less than vermin. And then there are the slum-dwellers, who fight poverty day in and day out just to be able to retain their humanity. One cannot help but wonder what prompts such disdain, disgust, and suspicion in the rich and privileged for the people who labour in their houses and their families. The divides exist in interactions between the slum-dwellers and the building residents, and in how they think and speak of each other. This becomes obvious when the slum-dwellers call the residential apartment building Lala Gram, when it is actually the posh L’Allegra. This simple juxtaposition of words illustrates the juxtaposition of worlds.

The torture in the book is described vividly and explicitly, and even though it tries to do away with voyeurism and describes the torture as clinically as possible, it can still give you nightmares for days (like it did to this writer). The writing is powerful enough to jolt you into worrying about your own safety. It is able to bring out the fear, the abject terror that comes with knowing that your child might be the next one to go. While the perpetrators debase themselves and slowly lose their humanity, the story manages to offer dignity to the less fortunate, especially to young migrants who are forced to live in squalor and cramped quarters because they have nowhere to go, to a sex-worker who is blamed for not being vigilant enough for the death of her child, to the men and women of Kandewadi who toil to make a life despite the everyday injustices they bear. It also manages to redeem a sensational-news-hungry journalist, who turns out to be more committed to the truth than to its coverage.

Twitter conversations are used throughout the novel to carry the story forward, and this would have been brilliant had it not been for two things. First, the book tries too hard to be contemporary and cool. The Twitter portions feel very forced and contrived. Second, the attempt to copy social media-driven news dissemination, in chunks of 140-characters, falls flat simply because no one bothered to look at the syntax. Throughout the book, one of the characters encourages people to look at their Twitter feed, but the syntax used is that of an email address. At first I thought it was a misprint, but this occurs repeatedly in the novel. Also, the narrator keeps emphasising the difference between Sita and Seeta, but nothing in the story explains this.

Ultimately, Greenlight serves as a warning. It talks about the dangers of the Internet, of having a complete stranger groom you online, this time not to hurt you, but to hurt others through you. Priced at ₹350, with 196 pages, it doesn’t take more than an afternoon to read. It is a book that is begging to be made into a movie, one that would provide a fast-paced and exciting script that could pass the Bechdel test.

[Bloomsbury India; ISBN 9789386349699]