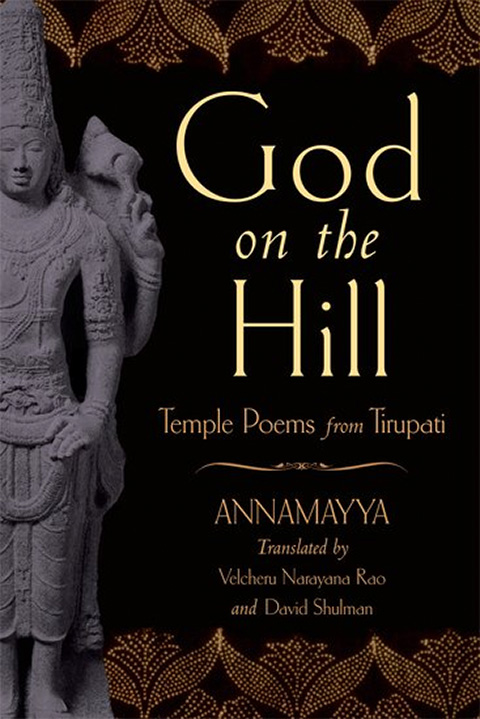

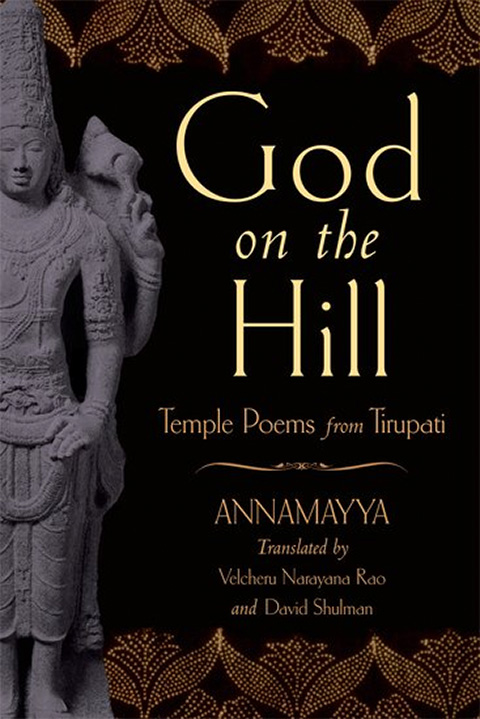

In a hilltop shrine in the temple city of Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh, a 15th century poet called Annamayya composed thousands of songs in Telugu for the god of the Tirumala Venkateswara temple or, as he was sometimes referred to, the god on the hill or lord of the seven hills.

Thirteen thousand of these poems were inscribed in the original Telugu on copper plates and stored within a vault in the temple. God on the Hill: Temple Poems from Tirupati is a 2005 Oxford University Press translation of a selected few of these poems in English. After I finished reading this collection, I found myself asking: why have more people not read this incredible book? A hint to the answer seemed to lie in my own biases. When hearing about it for the first time, I made two assumptions. One: the themes would be devotional. Two: the poetry in translation would make for difficult reading. Needless to say, I was proved wrong on both counts.

The poems are devotional in the way that a writer addressing all his work to one person is devotional. Annamayya wrote a poem a day, and this sustained preoccupation with god allowed him to explore a breadth of subjects—his own connection with god, god’s relationship with him and other devotees, god’s flawed nature, and god’s relationship with his wife. The poet-narrator does not hold the god at a distance, or himself. He scrutinises both closely to work through dilemmas about love, sexuality, faith and hypocrisy. He does not spare faulty logic, even when it belongs to the god on the hill:

Can you cut water in two?

Why hesitate? Take this woman.

The moon may have a dark spot,

but is the moonlight stained?

Her face may show anger,

but there’s no anger in her heart.

Despite the six centuries separating the composition of these poems and their readership today, they are accessible, relatable, and compelling. Annamayya invented and popularised a poetic form called the padam. His padam format includes an opening line, pallavi, which becomes the thematic line of the poem and is responsible for establishing the mood. The pallavi is followed by three verses known as caranam, each of which ends with the pallavi refrain. The editors describe the padam as “a highly integrated, internally resonant syntactic and thematic unit”. The poems were meant to be sung, and the raga for each poem was specified on the copper plates. The internal rhythm of the poems open them up to an audience who otherwise may not choose to read poetry. His images and metaphors are modern, clear, and evocative. Lines such as “time lures me/ like a deer behind a bush”, and ”time melts like butter next to fire” could easily have been written in this century. The translations are masterful with lines crafted in a way that allow both meaning and acoustics to come through. Take for this example this line: “The lotus spreads to the limits of the lake”.

An intriguing character in this collection is Alamelumanga, Vishnu’s wife, who is believed to an incarnation of the goddess Lakshmi. Their relationship is as textured and volatile as a human one. Annamayya sees her as Vishnu’s reckoning—

You bind everyone in the world in the round of life and death.

For this sin, someone has bound that woman

to your chest, not sparing you even though

you’re god.

The god on the hill is tethered to earthly experiences by a woman. There is this suggestion that she is part of his punishment, even while being a source of joy. On the one hand, the texts treat her as an extension of Vishnu rather than an entity in herself. It makes one uneasy to read: “If he keeps asking for more/ it does no harm/ He’s god/ I’m his wife”. On the other hand, she is wilful, articulate, and bold. She is aware of the influence she wields over him, and does not shy away from saying so.

I’m always in his arms.

He’s always laughing with me.

He’s the god on the hill

and I’m Alamelumanga.

Do I have to make a statement?

He’s my slave.

Time and again, the poems refer to the god’s inability to leave his hill. They appear to be reminding Vishnu of this mortal, commonplace predicament as a way of balancing the power he commands in Tirupati. Vishnu becomes interesting because he is not deified. He is allowed access to the whole spectrum of human emotions, flaws, and contradictions. In the end, Annamayya attributes the authorship of the poems to god himself. He chooses to think of himself as a vessel. Twenty million devotees are drawn to Tirupati each year to see Venkateswara-Vishnu. In the context of such devotion, it is understandable that Annamayya does not position himself as the creator of his work.

You are a god of a thousand names.

Who am I to praise you?

Still, you let me sign my name.

However, this seems too simple a conclusion at the end of a collection which is deeply personal. The poet spent an unidentified number of years (it is suspected that the thirteen thousand surviving poems are a fraction of his life’s work) composing these poems which, unsurprisingly, reflect the narrator, rather than Vishnu. His voice spoke to me because its lyricism was held in place with a deep practicality that he extended as advice to god himself—

Why worry about those who are free?

Release the ones trapped in themselves.

You really should feed the famished.

Who needs you to fill those who are full?

Why bring light to light?