The democratic ideal of freedom of speech has been in the news in 2015. Amidst previously inconceivable tragedy, as well as some almost as inconceivable Indian comedy, many have pledged to defend to the death your right to say that which they do not agree with. And it should be said because, in India, it unfortunately doesn’t go without saying.

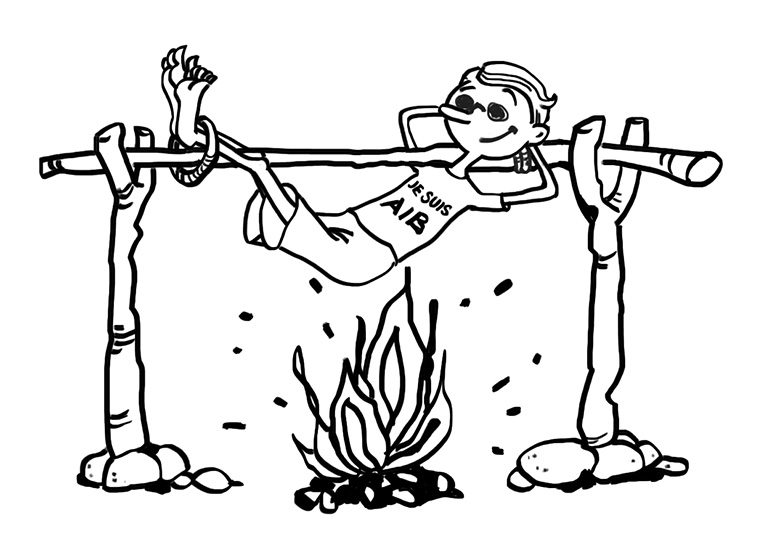

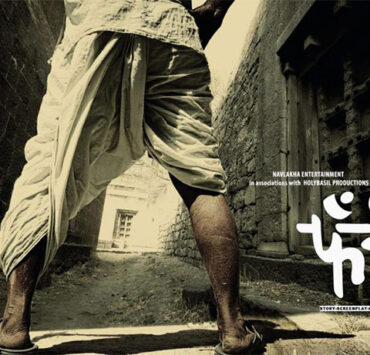

Illustration by Nirupa Rao.

On February 12th, an F.I.R. was filed against 14 persons involved with the All India Bakchod (A.I.B.) Roast for criminal conspiracy. Criminal conspiracy. I could write an article about how ironic/idiotic this is, but for now, I’m going to pretend like people who believe it is their birth right to restrict the thoughts, expressions, and lives of others to their own sad little world views do not exist. Forget giving them the importance they believe they deserve, I’d rather not give them any importance at all.

There’s another question that the issue has thrown up, which I think is equally important to discuss, and is far more debatable than the question of free speech itself. I’m not saying it is just an Indian concern. All over the world, people are busy honing their ability to take offence at the drop of a hat. But I think it deserves a place amongst the many questions being asked post-Roast. Because this isn’t just about defending to the death the rights of these comedians to make dirty jokes. It’s about building a larger, more public space in our country for satire. We really need it.

So what is satire and what makes it funny? Clearly, nobody likes explaining their jokes—they’d prefer it if you just got them on the first go, and if you didn’t, who cares as long as someone laughed, right? But when not getting jokes means that the wrong people are branded as racists/misogynists/homophobes/sacrilegists (don’t give a damn about that last one actually), then maybe an explanation is in order. Because it’s one thing when ridiculous, righteous right-wingers, and religious rabble rousers get their panties in a bunch when the whole world doesn’t take them as seriously as they do themselves; it’s another when more legitimate voices start to add a “responsibility” clause to a satirist’s freedom of speech, or (after vigorously condemning the attacks, of course) explain in excruciating detail why they’re not Charlie.

Let’s turn first to good ol’ Wikipedia, which defines satire as an artistic form of expression in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, corporations, government, or society itself, into improvement. Although satire is usually meant to be humorous, its greater purpose is often constructive social criticism, using wit to draw attention to both particular and wider issues in society. A satirical joke is nothing without its context. It sits inside a world different from the real one, but is guided by certain fundamental premises and rules. A joke that reveals to us this world it inhabits and then follows its rules is funny. A joke taken out of this context, as well as, of course, the general context of a satirist addressing his or her audience, is most often not funny.

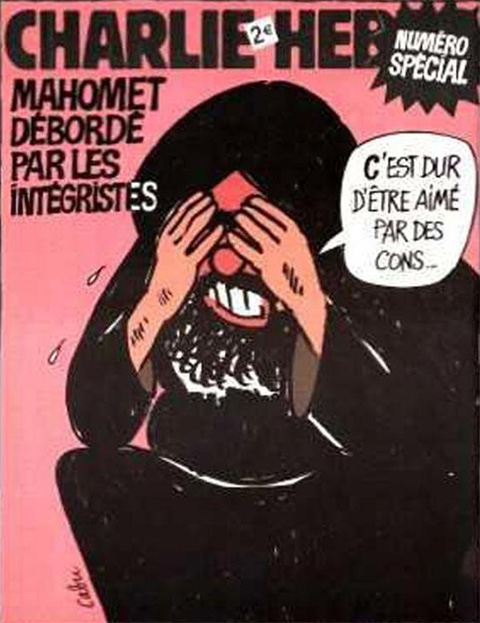

A joke taken out of this context is most often not funny. Image from Charlie Hebdo.

I know that according to today’s journalistic principles, this example is so last month, but take this cartoon by slain editor of Charlie Hebdo, Stephane “Charb” Charbonnier, portraying black minister of Justice, Christiane Taubira, as a monkey. On the surface, for someone who doesn’t know what Charlie Hebdo is and what it stands for, it could appear racist. And it did to a bunch of people on Twitter, who started circulating it under the hashtag #JeNeSuisPasCharlie.

Now let’s bring a little Context into the situation. First, anyone who’s familiar with Charlie Hebdo knows it to be a far left-wing publication that describes itself as, above all, “secular”, “atheist”, and “anti-racist”. Charb himself was in a relationship with a woman of North African descent, who also happens to be the former chair of the French Equal Opportunities and Anti-Discrimination Commission, so for him to draw a racist cartoon would be pretty stupid. Knowing this, even if you didn’t get the joke, you would consider the idea of the cartoon being racist absurd.

If you did get the joke, then you’re probably familiar with the French extreme-right party Front National, headed by Marine Le Pen, and their slogan “Rassemblement Bleu Marine”, which means “Rally Blue Marine”. You’re also aware of that time when a politician from the Front National shared a photoshopped image on Facebook of the minister in question as a monkey, shortly after which this cartoon was published. So, in the fictional world Charb created for this cartoon, the Front National’s poster bears its official slogan, “Rassemblement Bleu Raciste”, and its mascot, a black politician depicted as a monkey. By providing this more honest world as an alternate to the one we inhabit, he is calling the party out as racist. You might not think the joke is particularly funny, even after getting it, but you see how calling Charb a racist himself is a bit of a fuck-up, yes?

If you didn’t get the joke because you didn’t know or bother to find out the context, whose fault is that? Is Charlie Hebdo expected to stick to simplistic humour with no layers, context, or references to suit your convenience; to cater to a reader who it most likely never considered would be a part of its audience anyway? Or is the burden on you to not be lazy?

Who decides where the line is drawn? Image from Charlie Hebdo.

Let’s do one more. One of those prickly Prophet ones. Building up on the context we’ve thus far gathered about Charlie Hebdo, let’s add some background about the French attitude to politics, religion, corporations, and all other man-made constructions that claim authority over masses of people. While they might acknowledge the need for the existence of such institutions, they believe it imperative to not only criticise, but also subvert the authority of any figure within said institutions who abuses it. So cartoons of the Prophet don’t equate to, as some would have it, “mocking the marginalised and targeted” in a society, or whatever. Look at them instead as a sniggering, sometimes brutal, middle finger to religious authorities and fundamentalists who dare to use terror, power, and fear to get people—especially those not of the faith—to play by their rules. (Most often these rules have little to do with the religion itself.) Again you might find this joke unfunny, or some of the other cruder ones too lewd for your taste, but can you really fault the principle? Should they have been more responsible? Should women stop going to nightclubs or showing their cleavage? Who decides where the line is drawn? Victim-blaming is a dangerous game…

So in this one, where you have the Prophet débordé par les integristes or “overwhelmed by fundamentalists”, saying something like, “it sucks to be loved by idiots”, you’re being given a glimpse into the fictional world of the otherwise invisible Prophet who’s telling you what he really thinks—that Islam is not about fundamentalism. That’s exactly what non-Islamophobes say!

With all this context weighing down upon us, what say we look at the A.I.B. roast with wiser eyes, starting with some background on the tradition? A roast is meant to be a mock counter to the conventionally laudatory toast, and had its beginnings in a private comedy club called the New York Friar’s Club as far back as 1949. Rather than being showered with praise, the roastee is bombarded with good-natured insults, which he is meant to take with an equally good nature. In this mock world, it is, in fact, considered an honour to be roasted because it implies you’re special enough that given a chance, your jealous colleagues would jump at the chance to insult you. The genre of insult comedy gives those courageous comedians who would take it a chance to touch upon issues, hypocrisies, and human follies that would usually be swept under the carpet in polite company. When correctly understood, the concept of this constructed world can obviously generate oodles of risqué fun, but it can also be a very powerful tool.

This is especially true when applied to a society that reveres politicians and celebrities as gods, doesn’t like talking about sex, refuses to criticise religion, and prefers to believe homosexuality doesn’t exist. Taking this context into account, unlike what Aruna Rajan expresses in her article for Women’s Web, I think the comedians of A.I.B. were fresh, incisive, and brave. I think they understand comedic structure perfectly well; that when they were pulling Karan Johar’s leg for being gay, or Ashish Shakya’s for being dark-skinned, they were mocking what so many in our country truly believe. There’s no denying that the majority of us are patriarchal, fair-skin-loving homophobes, and all A.I.B. did is hold a mirror up to our society in a way that we can finally start to laugh at ourselves. That’s a helluva lot better than not talking about it at all.

Here’s a thought that may blow your mind: a serious issue can be taken very seriously and laughed about at the same time. The key is not to make a joke of something, but about it. Which is exactly what these guys did. Were they repetitive at times? Yes, it takes a while for an audience to build up all that context we were talking about earlier. Could they afford to tone down the crassness a bit? Sure, but every single one of us farts, poops, and thinks about sex, women included. Get over it. If it’s not your style, just click the little button marked “x” on the top-right-hand corner of your screen. It’s okay if everyone doesn’t watch everything. Just ask Seth Rogan and James Franco what so many Americans thought about their sometimes funny, always tasteless satire, The Interview.

But were they perpetuating sexist/homophobic/fair-and-lovely stereotypes? Were all the Jewish comedians at this roast of James Franco making all those Jew-y jokes to promote anti-Semitism? Don’t be insane.

So let’s give Aditi Mittal’s intelligence the benefit of the doubt and assume she got on that stage not to be humiliated by a bunch of patriarchal assholes, but to make a pertinent point about sexism, and make us laugh while she was at it. Let’s applaud Karan, a role model to many, for being an openly gay Indian man, let’s love Alia Bhatt for not taking herself so seriously, let’s slap Tanmay Bhat on his humongous back for calling out the hypocrisies of Bollywood. Let’s start being offended by our society’s real misogynists, homophobes, and hypocrites, instead of attacking those who are trying to be just the opposite.

When I watched the A.I.B. roast, I thought to myself, wow, are we ready for this yet? Now I’ve decided, who cares, because there will always be people—both “stupid” and “smart”—who insist on shoving their simplistic opinions in everyone’s faces. So be it. Let’s move on, with or without them.

A great read, thanks for this! It’s amazing how these basic concepts are still not the norm though…