I fell in love with Seahorse the way I fell in love with Amitav Ghosh’s Shadow Lines and Yoko Ogawa’s The Housekeeper and The Professor. Quietly. Deeply.

Shadow Lines was my first teacher in non-linearity. I discovered that time can linger, halt, stagnate, freeze, and shatter all together, instead of just contract and expand in the ways I was accustomed to thinking about it. The Housekeeper taught me that time is an animal with no bones. It takes the shape of its vessel. It percolates in the cracks. But in the absence of external custodians, it has no form, no direction, no sanity pinning it to our world.

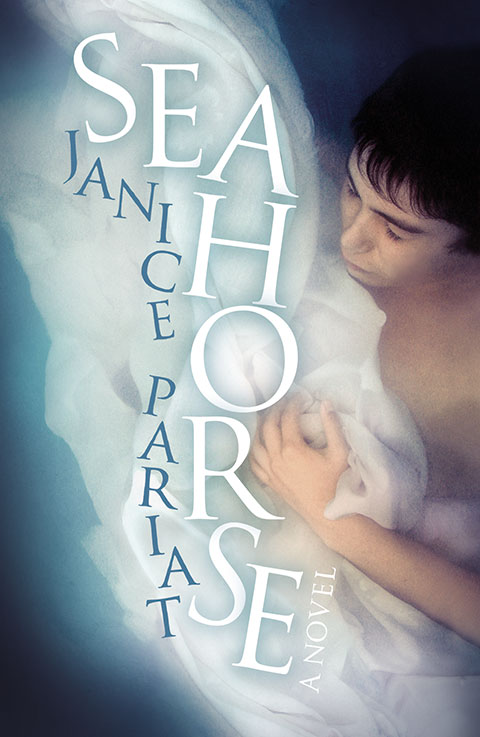

Janice Pariat’s Seahorse.

In Seahorse, time is tethered to love, to obsessions, to personal myths. But time doesn’t follow the objects of love as they travel beyond the scope of the story. Time stays with those left behind—torturous, comforting, and nourishing as only an obsession can be.

In many ways, Seahorse is my story. In some ways, it will not be my story for many years. I can only imagine that Janice Pariat built this novel with a great deal of love and care. Every name is a handpicked fate. Nehemiah: builder of new worlds. Yara: small butterfly. Nicholas: victory. Every reference to art and literature expands our understanding of Nehemiah, of the plot, of ourselves. Every London pub and ale listed in this book brings to life the city that Nem believes is filled with old light. Every homosexual love scene is humane, absorbing, and real. There is so much intricacy in this novel, and Pariat saves it from turning into clutter.

In the simplest sense, it is a retelling of Poseidon’s love for his youthful devotee Pelops. Nicholas, an art historian, falls in love with Nehemiah, a student at Delhi University. On the one hand, Nehemiah sees their lives as interspersed in the entwining of their book collections. On the other hand, Nicholas addresses Nehemiah affectionately as his blank slate. He is set up as a student, as an explorer, as a builder by Nicholas, and it is this image of himself that he cannot escape as clock time progresses. When Nicholas (the enabler; the mind that stitched Nehemiah together) disappears, time breaks up into all its moving parts. The remainder of the narrative is consumed with Nicholas’ absence, moving between memories of him in Delhi and questions about him in the years that follow. Nehemiah moves to London in a subconscious, desperate move to collide his world with Nicholas’ again.

Deep into his narration, Nehemiah says, “In the end we are all cartographers—looking back at a map of our lives. Marking out the uneven course of our existence, hoping there’ll be no disappearances, of ourselves and the people we love.” He is an incredibly self-aware narrator as he moves between his present and his past to accurately tell his story across time.

I was a little disappointed by the closing chapters of the book. On the first page of Seahorse, Nehemiah says, “How easily we are fooled by neatness.” But the ending seemed too neat. The story became too repaired in the end to do the reality of its fractures justice.

All in all, with Seahorse, Pariat has written a compelling novel whose prose bridges the gap between fiction and poetry. This book goes a long way towards propelling Indian fiction in the right direction.