In 2008, I watched a film about a boy who grew up in the dark, grimy underbelly of the socio-cultural beast that is India, a boy who fixed his eyes upon a target unattainable to those on the wrong side of the developmental juggernaut. Obsessed with the object of his desire, the boy compensates with cleverness where lacking in formal education, makes up with charm where confused about what may or may not be socially appropriate behaviour.

In the darkness of the movie theatre in a white, upper-class suburb of Chicago (I was living there as a student at the time), I could hear people sobbing into their handkerchiefs around me as the boy schemed his way to where he wanted to be. The audience let out collective sighs at the boy’s misfortunes, cheered his smallest victories, and at one particularly poignant moment, even rose spontaneously for a standing ovation. The film had managed to present a picture of those on the periphery of Indian society like none other. It wiggled its way into the hearts of film lovers all over the world, even those with an appetite for strictly conventional fare. In the year of Milk, Frost/Nixon, and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, this film swept the biggest awards around, and most people seemed to think it deserved all the acclaim.

The film was Slumdog Millionaire.

It was the wrong film.

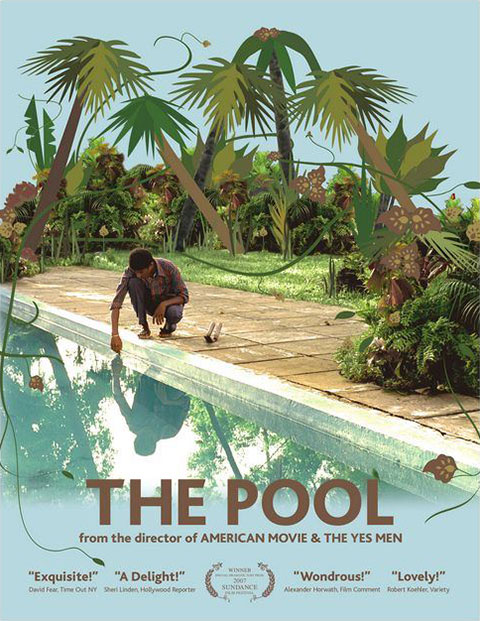

The Pool is everything Slumdog Millionaire was not.

That same year (or the previous year, depending on which part of the world you watch your movies in), a somewhat similar film was released, albeit to limited audiences. It won acclaim on the festival circuit but then disappeared, leaving behind a faint trace in the form of glowing critical reviews. It is, like Slumdog Millionaire, a film about a boy who grows up at the bottom of the economic ladder in India, and desires something quite unattainable to one in his socially disadvantaged position. The film is about his ingenuity in using his limited resources to achieve his goal, and the complexity of his emotions as he gets closer to attaining it.

That film is The Pool, and thematic similarities aside, it is everything Slumdog Millionaire was not.

The central character of The Pool is a teenaged boy named Venkatesh (Venkatesh Chavan), a native of a village in Karnataka. Venkatesh works as a migrant labourer in Goa, and among the multiple jobs he does to keep afloat are cleaning and washing at a local hotel, and selling plastic bags to shoppers at a busy market. He spends his spare time and money with his best friend Jhangir (Jhangir Badshah), a cleaner at a local restaurant. A few years older than Jhangir, Venkatesh sometimes acts the older brother in the relationship, explaining things to the younger boy, mollifying him when he is upset, and bringing him a box of homemade chutney every time he makes a trip back home. There is hardship in this life but no drama: sometimes, Venkatesh talks to Jhangir about going to school, becoming a “bada aadmi” (big man), and earning a lot of money, but these discussions are laced with as much sardonic humour as genuine hope. The fine print here is that they know this is how life is going to be, and the acceptance of this reality makes it okay for them to entertain their outrageous dreams—until Venkatesh sees a swimming pool, and that vision of cool, clear water splashing on powder blue tiles unravels the understanding he had arrived at with the circumstances of his life.

More intriguing than anything else is the significance of the titular pool.

Spying on the luminescent pool from on top of a coconut tree, Venkatesh becomes obsessed with it, with the idea of bathing in it. But the pool belongs in the bungalow of a very rich man, Nana (Nana Patekar), and his grim, reticent daughter Ayesha (Ayesha Mohan). The real and metaphorical walls that surround this house have been erected especially to keep those like Venkatesh out. The object of his desire lies in a world that is visible and close, but almost entirely inaccessible to him. And from that point forward, Venkatesh directs his wits and energies towards somehow finding a way of penetrating into this world.

Given the setting and the year it was made in, the film lends itself to some obvious comparisons with Slumdog Millionaire. They’re both about clever and resourceful Indian boys who have grown up in poverty. They’ve both been directed by white men who needed to familiarise themselves with the geographical and cultural terrain of India before making their films. They both feature a combination of professional actors, and kids who actually live the lives they depict on screen (Venkatesh Chavan and Jhangir Badshah are the non-actors in The Pool.) But while British director Danny Boyle of Slumdog Millionaire chose to make a film that was part homage to Bollywood and part annotated catalogue of every white, western stereotype of the developing world, American indie director Chris Smith crafted The Pool in a realist tradition precious not just for its scarcity, but also for the sincerity it lends the storytelling. Of course, this stylistic choice is precisely the double-edged sword here—while the business of film distribution and exhibition has an unfortunately small demand for material made in this tradition, mostly finding takers at film festivals and independent theatres, the realism of the film is also what makes it appealing.

When we reach the main point of conflict in the narrative, which is that Venkatesh wants to bathe in the pool, the film makes us privy to his machinations, makes us delight in how he finagles his way into Nana’s service and how he woos Ayesha—not for romantic love but for friendship—so she might invite him to use the pool. But once Venkatesh’s connections with these rich people have been established, the film leisurely spreads its wings in other directions, exploring themes that creep up on the audience so discreetly, we hardly realise how or when the questions the film is asking—and the questions we’re asking of the film—got so much bigger than just a boy’s desire to bathe in a sparkling pool. With regard to Venkatesh’s relationship with Ayesha, we are touched by the way in which it enriches them both, but we are also nervous at its tenuousness. The doubts we have—will he do something to offend her?—are telling of our own pre-conceived notions of how people may behave depending on their station in life. Similarly, in Venkatesh’s conversations with the horticulturally-obsessed Nana, we learn about the pressures of his life in his village, and about how he has to fend for his mother and his sister. But by the time we reach the point where Nana offers Venkatesh a way out by funding his education—a dream Venkatesh mentions multiple times at the start of the film—we know that despite the lack of overt changes in his life, the way Venkatesh perceives the world has altered, and going to school is somehow no longer as obviously desirable as it used to be.

But more intriguing than anything else is the significance of the titular pool. From a visual that evokes desire in Venkatesh simply because of its unfamiliar beauty, the pool goes on to symbolise his aspirations, and the distance between those like him and those like whom he thinks he wants to be. And it evolves further from there, too. In my final understanding, the pool hints at the untold tragedy of Nana and Ayesha’s family, becoming, at once, a symbol that unites all the characters in their personal misfortunes, but also distinguishes between them in its complete dispensability to the rich.

The Pool isn’t the kind of film that follows a traditional story arc. Of all the narrative threads running through it, only one—that of the relationship between Jhangir and Vankatesh—undergoes overt transformation. Everything else remains just as it was at the beginning, except for that vague feeling that something has changed under the surface and that actually, nothing is the same as before. The film is a narrative of survival, not triumph; of life, not drama. It is insightful, light, even funny in parts—the only real tragedy the film openly addresses is the one involving Ayesha and Nana’s family. And yet, the ending manages to deliver the heaviness of the larger unchangeability of things, and does so with grace and sensitivity.

Watch The Pool. It’s probably not running at a theatre near you, but you can find it on your favourite online store for a small fee that is absolutely worth it.