I. REMEMBERING

The first time I was afraid of our love was when you disappeared for three whole weeks. Your phone told me it was an invalid number; your workplace was shut and your flat wasn’t where I remembered it to be. I stared at the walls of the building, willing it to turn into a red-bricked, two-storeyed house in which you baked your warm garlic bread and made your homemade cheese sticks. It stared back at me, blank and blue. By the end of those three weeks, I almost forgot about you. If someone were to mention your name to me, my stomach wouldn’t lurch and my face wouldn’t melt into a grin. Almost.

I wish I could say that there was one exact moment in which I knew I was in love with you: a factual event that made it real, a memory I could recall and say, this was it. A kiss, perhaps. You and me sitting by the lake in stealth, our cold bottle of whisky and our warm bodies in Delhi’s December. Your fingers were numb, looking for warmth inside my scarf. Our breath was misty, my teeth were chattering, and we were trying to laugh as softly as possible. But I knew by then. I knew when I let you run your hand over my eyebrows, I knew even before I kissed you first. I knew before we jumped over the short wall into the Deer Park to sit by the lake and get drunk on our cheap whisky. I knew before you grinned cheekily and said you knew just the place. I always knew. I’ve gone back there only once, since. I took a walk there last February to look at the deer. I walked along the west wall, by the jogger’s path, over the ducks’ lake, and through the funny exercise equipment. I didn’t think of you at all.

The first time you disappeared also resulted in our first fight. When you came back, I was angry, so angry. I was confused and anxious, convinced you were scamming me somehow. You had tears in your eyes, but you didn’t scream and you didn’t think I was crazy. You were hurt, but you didn’t say anything to make it my fault. You tried explaining yourself to me. I can’t remember what you said that first time to pacify me, but I remember sitting next to you with my knees knocking against yours. It was the only contact we had that day, the only contact that we’d had in three weeks: but it was enough for me to trust you. It was enough for me to remember how much I loved you.

Some memories of you feel like they never belonged to me in the first place, like a book stolen inadvertently from a café or a library.

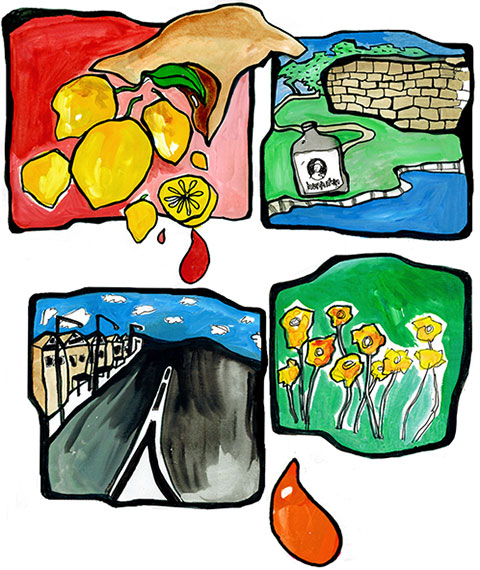

Do you remember the day we jumped over the wall into Penny Lane? You bought me a raspberry ice lolly and we spoke about everything in the world. We lay on our backs and watched the clouds go by, there, beneath the blue suburban skies. We could hear the trumpets at the roundabout and smell the poppies on the tray. From a distance, we watched a banker and wondered if today was the day he’d rush into the pouring rain. We mused about everything, shook our heads, and said, very strange. When we left, we knew we’d probably never find our way back again. It would remain that special place we stumbled into, but never found again.

But soon, you disappeared again. I don’t know how long you were away for. I can’t remember what I did during this time. It was time that wasn’t time, for me. It was as if I was in suspended animation; as if I had no real body, no sense of being; as if I wasn’t. A singular feeling had taken over me: an implacable loss. It was as if I was the thing that was lost; truly lost, as if I had disappeared off the face of the earth. Unmapped. Forgotten.

And, as always, you brought me back: you, with your brilliant smile and your perfect toes, your smell of freshly baked bread and old books. Your fingers caked with the grime of dusty libraries and a hundred thousand cigarettes, your knees knocking against mine, your hands holding mine firmly.

II. FORGETTING

It took me a long time to figure out what was happening, that it wasn’t you who was disappearing, it was I.

I couldn’t have done it without your help. By the sixth or the seventh time, I learnt how to recognise the signs. Insecurity. Paranoia. Anxiety. Grief. I learnt to diagnose what was really happening. I learnt to tell what I was missing. Specifically, I learnt how to tell who I was missing. All my answers led to you, love. Everything I didn’t understand about me was you. Me, flitting between nothing and everything. You, keeping me focused. Me, holding on to you.

You were keeping me real. I was being real for you.

Eventually, I came to understand my condition: I constantly disintegrate and reintegrate myself with the world. Yours, to be precise. For a few moments, sometimes days, weeks, or even whole years, I cease to exist for you. It is, of course, difficult for me to know this—it is difficult to time things that are out of sync, so to speak, with what we perceive as reality.

For me, it begins with nothing but panic. My whole body starts to shake with anxiety and confusion. The ground pulls at my stomach, as if tugging at it. Everything goes out of focus. The world feels like a distraction, like a set of keys that I forgot inside the house before I locked it. Before I can blink, before I can orient myself to this feeling, before I know what it is that I am missing, I think of you. Sometimes I feel you, instinctually, as if I know who is calling me before the phone even rings. I try to grab at this, as though it is a real thing. It is the only thing keeping me in focus, the only thing keeping me here.

III. PAPER CUT ON MY TONGUE

You once told me about the first time you spoke to your best friend about the issues we were having. It was the first time you gave me a glimpse into how much it was bothering you. You told me you were questioning yourself: you didn’t know what to think and whom to believe anymore. You didn’t think I was real, you thought you were making me up. Of course, you had your reasons. Real people don’t disintegrate into nothingness when you stop thinking about them. Not the way I did, anyway.

You said you thought you were going insane. “But then you turn up,” you told me, “with your crooked teeth and that dreadful sense of humour. I couldn’t make you up if I tried.” You paused for a second and said awkwardly, “Um, and then there’s that fabulous sex.” I laughed, and I agreed. There was that fabulous sex.

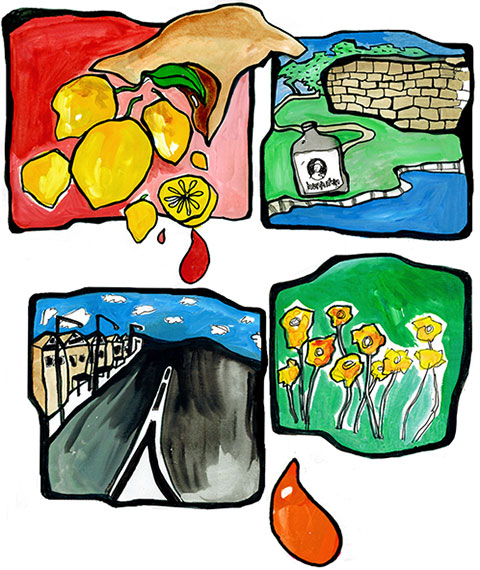

In response, I told you about an afternoon many years ago when I got a paper cut on my tongue. On a day in the middle of August, my house was filled with lemons that came in sacks: fresh from the farm, sharp with the smell of citrus, rich with the promise of pickle. I was leafing through a glossy recipe book, sucking on sugared slices of lemons, looking for something interesting to cook. I don’t quite remember how I did it, but as I was turning a page, I gave myself a paper cut on my tongue. As quickly as I could, I found some ice cubes and popped them in my mouth. I ran to the bathroom and stared at the side of my tongue. It was bleeding bright red. As I stared at my bleeding tongue, a remarkable thing happened. It lasted for all of a moment, this strange, remarkable thing, but on that moment hinged all of how I understood my reality. In that singular lemon-stung paper cut moment, with a bleeding wound less than a square millimetre in size, my world changed.

You were justified in giving me an almost patronising look, though I wasn’t being dramatic. That day, it changed my life. In that singular moment, I flickered like an old television set coming on, and for what may have been a whole minute, I wasn’t there anymore. I couldn’t see myself in my mirror, I couldn’t feel the wound on my tongue, I simply wasn’t there.

I told you that story to explain to you how thin the line between what we think is real and not is. I told you the story because I wanted to explain the origins of my problem: I wanted to tell you about the first time I suspected the truth about myself. Of course, as I was telling you the story, I didn’t stop to think about the ramifications of my doing so. I didn’t comprehend the bigger picture. I thought I was being clever, but really, I was only making it worse for you.

IV. THE END

Inevitably, we broke up. It wasn’t a sustainable relationship. Not for you, at any rate.

I was distraught when we did. I couldn’t understand why my reality was allowed to be an obstacle to our relationship. I searched all over the world for people with my condition. I found someone with a sister who wasn’t real. I found someone with a six-year-old child who didn’t exist. I even found a kid who knew a friendly tiger with the same maladjustment to reality as me.

The human mind has an infinite capacity for imagination and lies, but very little for truth or fact. Everything we see, do, hear, feel, say, believe in, and remember is made up in our head most meticulously and systematically, using layers and layers of sensory perception through a process that is nearly impossible to map or replicate. All of it is assembled together neatly by our brain, dumbed down to the level we understand, and handed to us on a platter. Essentially, as a species, we are constantly lying to ourselves.

In most of my endeavours, I try to understand why my entire self decides to unravel and disintegrate. Most of the human body is made up of space, so the obvious assumption is that the physical body dissipates and comes together seamlessly enough. What interests me more is the suspension of the human mind. I assume that people like me, with minds that are much less capable of lies and imagination, are unable to grasp reality and recreate it for ourselves. I assume that truth, essentially, sets us free.