Annie Zaidi reminds one of a gypsy whose adventure unravels as you count the number of colourful hats she has donned. A journalist, playwright, essayist, poet, and storyteller, her ability to express variedly in multiple voices is laudable. It also reflects her honesty and sense of commitment to the subjects she explores.

In her latest anthology Love Stories #1 to 14, Zaidi’s short stories are much like her in the vast landscape they tread. They are facets of love, characterised by chilling precision, debilitating restlessness, and naivety of dream and wish. Zaidi craftily canonises insignificant everyday characters and their emotional seesaws in a way that evokes both pity and pleasure. The characters’s invisibility in the everyday scheme of things assumes a certain grandeur in these stories as they hinge on a delicate thread, one that bridges the gap between hope and disconcerting failure.

This collection offers no catharsis; it is as real, poignant and uncontained as the discerning mind’s monologue. The author spoke to us about this and more in an exclusive interview. Read on for excerpts—

“It is always the story that must determine its genre.” Photograph by Faiz Tajuddin.

You’ve dabbled in multiple forms of writing. Was short fiction a genre you wanted to explore or was it just most suited to express your characters and their worlds, as you saw them?

It is always the story that must determine its genre. Not every idea or character that you write can be drawn out to novel length. And not every narrative can be squeezed into the sharp, intense contours of a poem.

Is Love Stories a culmination of many years of observations and experiences? It is highly perceptive and nuanced, precise even, when it comes to articulating elusive emotions.

Yes, it is. Although, I think almost all good writing is a culmination of sorts. Not only of our own lives up until this moment, and those of others who are in our worldly and imaginative orbits, but also the culmination of our reading, our conversation, and consumption of other arts. Ideas take years to write, but they take a lifetime to occupy our minds.

The quirky, numbered titles are misleading; I expected a funny, rom-com take on love! Is there a story to how you arrived at them?

I had begun to write the stories sans title. For the sake of convenience, I began to number them. The only story for which I did have a title was The One That Was Washed Up by the Tide. That was written to be entered in an anthology (which never materialised), and I knew what the story was about—a city by the sea and the beach as a symbol of freedom and peace and unattainable longings. So I came up with a title. When I decided to use it as part of my own collection, its title showed me a way to build a series of titles, each starting with ‘The One …’. Eventually, we decided to stick to the pattern of dual titles for all the stories.

The lack of names or fully etched out characters stands out; was it a deliberate attempt to communicate the universality of love/lack of love and its symptoms as manifested in everyday characters—the migrant maid in a city, the middle-aged woman who travels by the local train, a couple in a failing marriage?

I started writing #1, which is a very self-contained sort of story. It is about a man and a woman, and their home. Almost nothing intrudes into this relationship and so, it was natural to just write it as ‘he’ and ‘she’. I did not feel the need to give them names. But as I wrote more and more, I realised that the lack of names was bringing freedom with it. The protagonist could be everyperson. In my own head, of course, they did have contexts—they wore a certain kind of dress, they talked with definite accents. But with this collection, the only thing I was sure of was that I must focus on my characters’s feelings. Like catching a brief glimpse of the inside of someone’s mind, feeling what he/she feels. Social contexts may have gotten in my way, so I kept them out.

The characters only seem like a medium for the ruminations of the mind, for the characters are only what they think.

Yes, that is what I wanted to do. I wanted to tell these stories from the perspective of one central character, and to examine their experience of love or heartache. So, it had to be mainly an internal dialogue. I allowed the characters to act on their feelings as well, but the time capsule is mostly small, so the dialogue and action is limited by their present situation.

Sometimes, through interior monologue, the prose spirals into a delirious ramble. It is an affliction of love, the anxiety that comes with it, the contradictions. But can prose always bear the weight of that effectively?

You’ll have to tell me which portions of the book sound like a delirious ramble, and perhaps I can decide how much of it was intentional. But on a serious note, prose can bear the weight of almost anything. If a certain delirium is being communicated to the reader and it is not boring, then that would be effective prose. That’s my view, anyway.

In a culture where ideas of love are fashioned by Bollywood and historical epics, and where love is plagued by grandeur, where would stories of real people in their immateriality, particularly in an ephemeral form, stand?

I don’t know, really, if my work will stand. But I grew up on an insane Bollywood diet, so there’s a fair bit of romanticism stuffed inside my head. And I love historical epics, myths and legends, folk romances. Yet, these are the kind of love stories I ended up writing. How did that happen? Perhaps because my reading was so diverse. Perhaps because I began to watch a different kind of cinema. Perhaps because I took inconvenient decisions, or because my work shaped my politics, which in turn shaped my writing. That’s how it works from a creative perspective. Honestly, I am more worried about whether my work will stand for me, rather than for others.

The way I see it, the 14 stories could easily reshuffle themselves into one. The voice has a certain consistency to it. Wouldn’t that have been easier to draw readers into?

Do you mean to ask why I didn’t write a novel instead? It never felt like a single story to me. Besides, I don’t like to think about how readers will react. It is my job to tell the story. If it fails to draw readers in… well, then it fails.

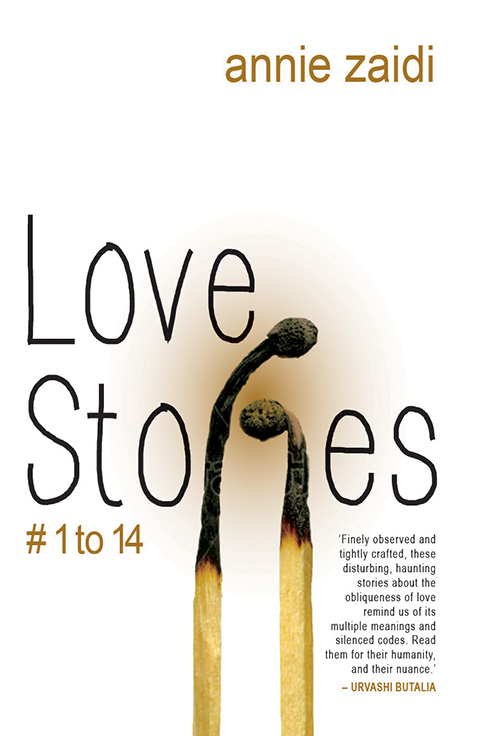

The motif on the cover captures the essence of the book for me. Fluid, shifting, amorphous—the nature of love.

Indeed, it does come close to the essence, at least in several of the stories. I had wanted a simple cover, with a single design idea or pattern. The designer Arijit [Ganguly] came up with some other options but this cover appealed to me immediately.