It’s not an easy task to introduce Byomkesh Bakshi to the general reading public. As a publishing house and as a translator, you’d have to factor in the large number of fans Sarandindu Bandyopadhyay’s fictional detective already has; or even tougher, grapple with introducing such a cult character to a reader for the first time.

That would perhaps explain why The Rhythm of Riddles—a collection of three short stories translated from Bengali into English by Arunava Sinha—is so securely padded with a brilliant introduction and a translator’s note on both sides. That way, should the book “fall”, any bruises will only be borne by either an overhyped introduction or an inept translation. But does the book fall?

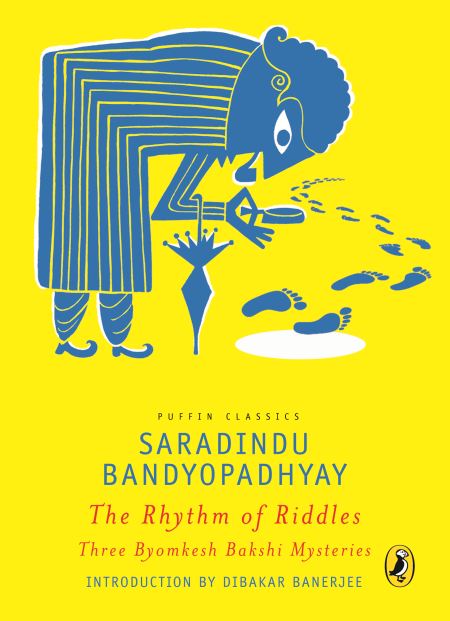

The Rhythm of Riddles book cover.

The blurb insists the stories are “action-packed”, “breathless”, and “thrilling”. Dibakar Banerjee’s introduction to the stories, let it be known, is nothing short of spectacular. If you had no prior experience with Byomkesh Bakshi and his cultural footprints in Indian literature (in English and other Indian languages), Banerjee’s your man. In a Hitchcockian vein, Banerjee builds the atmosphere for reading such a book. At once deeply personal and general, the introduction is deliciously wicked with its slowly building, but relentless sense of foreboding and mystery.

Banerjee ushers you into a room with a couch next to the window and as you settle in and pick up the book, he shuts the door behind him politely, insisting you will have nothing short of an epic time.

Unfortunately, you don’t. The three short stories, The Rhythm of Riddles, Byomkesh and Barada, and The Death of Amrito struggle to work up to the sort of pace you’re promised in the blurb. The Rhythm of Riddles is the shortest adventure, and the most disappointing. Perhaps because of its length (30-odd pages), there is simply no time to gather any tone or atmosphere of the world the gruesome murder has occurred in. The time it takes to get from socialising-murder-shock to problem solved is pitiful and by the time Byomkesh waltzes in with the news that he knew the murderer all along, you lose any invested interest in the story.

Byomkesh and Barada is marginally better, but for a story that could do so much world-building with the supernatural, eerie elements in it, it does little to tantalise. It’s not all bad, however. We’re let into a little more of what Byomkesh sees and analyses around him and you’re genuinely curious towards the end of the story to find out both who and how of the murder.

The Death of Amrito is by far the best-written of the three stories. It is also the longest, but the length is not a factor as much as Sinha’s translation in this one. In both The Rhythm of Riddles and Byomkesh and Barada, Sinha’s translation comes across as extremely stilted and abrupt. Although he preempts such criticism in his note by letting us know that he was trying to translate through both language, and era, you can’t help but wonder if ‘formal’ necessarily needs to mean ‘awfully staccato’. As a reader who hasn’t read the original in Bengali, even arming myself with a translator’s note doesn’t help me in approaching what Byomkesh Bakshi is or was if the language he is introduced to me in paints him as a smug genius in words that are trite and dull. The Death of Amrito manages to absolve some of Sinha’s pitfalls with the other two stories. Right from the first few lines, there is an atmosphere, a thick, velvety air of mystery that you’re immediately sucked into. The plotline is both dense and believable, something The Rhythm of Riddles tends to lack in.

The problem with The Rhythm of Riddles is that it assumes a certain amount of nostalgia on the part of the reader: either based on early memories of reading Byomkesh Bakshi stories, or induced by that elaborately constructed introduction. It certainly isn’t a disaster, but is it any better to sit through a book that won’t necessarily leave an impression on you? The Rhythm of Riddles is a beam of weak sunlight on your arm as you sit next to the window. It is non-intrusive, mildly interesting—at times, pleasant—but ultimately tepid.

[Penguin Books India; ISBN 9780143331827]