How does a television show based on a cult fantasy series become a mainstream success? By faithfully following the writer’s vision, not just in terms of the story and pace, but also in its tone.

Game of Thrones, based on the first novel of George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire cycle, is brutal, to say the least—just like the books. 15-year-old boys are forced to lead armies to battle, women are routinely raped as part of ‘war’, and sometimes just the simple act of not actually doing anything can get you strung up to serve as food for crows. As one of the characters puts it, in the game of thrones, you win or you die. There is no middle road.

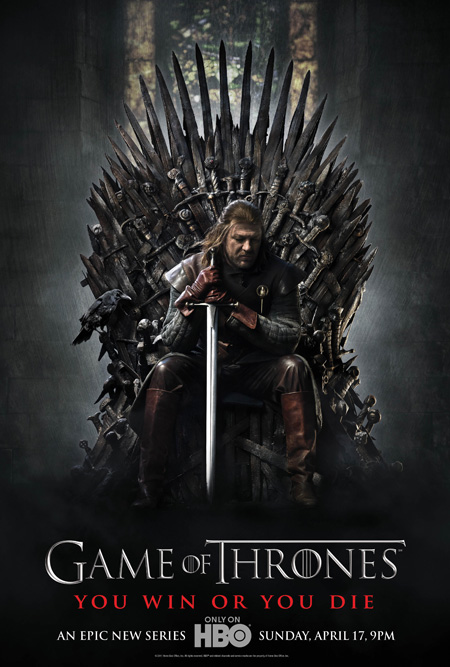

H.B.O.‘s Game of Thrones.

Don’t make the mistake of dismissing George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire cycle as just another medieval fantasy series with wizards and dragons and swords with names. For ‘just another fantasy series’ is exactly what it isn’t. You thought real life is complicated? Read A Game of Thrones, and your head will feel muddled, what with the number of characters, their complex motives, the strange-yet-familiar universe that they inhabit, and the fact that you simply don’t know who to root for. And that’s just the first book. To put it simply, this is no simple, black-and-white tale of good versus evil. This is a many-layered story, told by a multitude of fascinating and enigmatic characters, all with inscrutable intentions.

Set on the continent of Westeros, A Song of Ice and Fire weaves together three story lines. One is the dynastic civil war featuring various noble houses, chiefly the Starks, Baratheons, and Lannisters. This struggle for the Iron Throne is going on at the capital, King’s Landing, and elsewhere in the seven kingdoms. At the same time, Daenerys Targaryen, the exiled daughter of a king who had been slaughtered along with his family 15 years ago, is trying to stake her own claim to the throne. She has married a horse lord, Khal Drogo, a fearsome Dothraki warrior, who commands 40 thousand men and who has promised his bride that their son will one day rule from King’s Landing. While all this is happening, the long summer of Westeros is ending and a generation long winter is setting in. In the far north of the kingdom, beyond the massive wall of ice, which was built to keep out uncivilised wildlings and unnamed, terrifying forces, something dark and terrifying is rising.

Such a complicated storyline is never easy to adapt for the screen, which is why it is amazing how seamless the transition seems to have been for Game of Thrones. The producers have taken great pains to achieve what Martin had envisioned (the writer was consulted throughout the making and even wrote one of the episodes): they’ve even used actual animal corpses in some scenes. In fact, in Tywin Lannister’s introductory scene, it’s no prop that he’s so expertly skinning. That’s a real dead stag.

This being an H.B.O. production, plenty of nudity is expected. What is pleasant, though, is that not all of it is gratuitous. Certain scenes featuring skin convey the character’s situation and personality more effectively than pages of dialogue. An apt example is Emilia Clarke as Daenerys Targaryen. When we first see her, her nudity is a symbol of how vulnerable her position is. She’s to be sold to the Dothraki lord by her brother Viserys, in exchange for an army which will help him storm King’s Landing. This scene is painful, as Viserys looks his sister up and down, like she’s not a person and tells her to be womanly in order to please the Khal. We then see Daenerys being raped by her new husband. There is nothing titillating about the nudity in these scenes and Dany’s anguish is heart-wrenching. However, as she slowly gains confidence in her new role as Khaleesi, and begins to grow fond of her husband, the effect of her nudity changes. There is a new tenderness, as Dany tells her husband that she wants to see his face as they make love. By the end of the first season, in the final scene, Dany stands proud and naked as her people bow before her power. Her nudity now has become a symbol of her self-assurance and her complete acceptance of her destiny.

The acting throughout is top-notch. Maisie Williams as the feisty Arya Stark is splendid, as is Sophie Turner as Sansa Stark. Turner has a particularly difficult task here, since Sansa isn’t a character the viewer can understand or sympathise with instantly. But the actress does a wonderful job of essaying Sansa, showing her transformation from a typical, dreamy teenager to a mature adult on the verge of cynicism. But the real star of the show is Peter Dinklage as Tyrion Lannister. You can see that his Golden Globe win was well-deserved.

Having covered the first book, the show moves on to the second book this year (April 1). What was already a complicated story, with dozens of characters, is set to get even more so. Martin himself has admitted that his epic has become so complex and unwieldy that he often makes little errors that his fans point out to him. Maybe the show can avoid doing the same.

love this :)

Thanks Stuti!

good stuff

Thanks, Krishna!

Woah! Good writing here, great read!