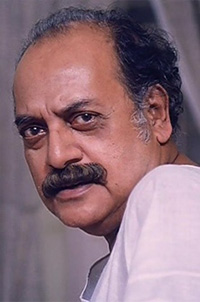

The immensity of certain incidents in the history of colonisation is such that there remains no room for subtlety. “Everyone is equal in America with a gun in hand”—Utpal Dutt says it loud and clear in the prologue of Rights of Man. The play reconstructs the trauma of the Scottsboro trials of 1931, inflicted on the collective conscience of the Africans settled in America and outside. In a scathing voice, Dutt revisits the horrors of racial discrimination, injustice, and denial of human rights.

Words like ‘propagandist’ and ‘revolutionary’ have been widely used as descriptors for Utpal Dutt.

The attitude of an ordinary Alabama citizen towards the ‘nigger’ reflects in the character of Paint Rock’s station master, Edward Crosby, in act one. The racial superiority of the white man is emphasised through social structure, with blacks hired as slaves. Crosby’s assistant Philip is repeatedly snapped at with words like: “Don’t stare at the engine, niggers don’t drive trains. The union has laws. You wanna be dead?”

The fact that Alabama is not New York is mentioned repeatedly. Alabama was profoundly intolerant towards Jews and Negros. One of the characters explains how Alabama revels in the idea of slow and brutal torture, narrating an incident where a black was tied to a lamppost, lashed and slithered in front of his wife, who was conned to kill her husband. These passing anecdotes, well crafted by Dutt, run shivers down the reader’s spine.

In act two, the court trial of Haywood Patterson is described as some kind of spectacle. A member in the audience remarks that he has got lunch to enjoy the agony of a “negro rapist”; a woman excitedly states that her husband works at night and it was hard to come but she still came. The atmosphere in the court room reminds you of the law systems in Athena in Greek mythology, where the misdoer was thrown off to lions, much to the crowd’s uproar and excitement.

Dutt’s clever one-liners are impressive. In an interview before the trial, chief prosecutor Thomas Knight quips “We’ve got a strong case, I can say this with my faith in God. And God is white.” In the same scene a reporter says, “Are you saying that nigger women are ladies?” The trial is written as the greatest parody of justice. Even before the trial begins, the chief defense attorney objects to the absence of a Negro juror in the panel. This is only a subtle glimpse at the faulty law system of the United States.

The six-year-long trial is effectively condensed into a few pages, lending some critical insights into the American law. By the end of the book, one has sufficient reasons to believe that the trial is nothing but a farce in the name of justice—one big circus. The striking aspect of Rights of Man is Dutt’s use of language, which is both clever and sardonic. The verbal exchanges between Knight and Leibowitz are immensely captivating, so much so that you are reminded of contemporary writers Harper Lee and Jeffery Archer for their proficiency in legal lingo.

By the end of the book, one has sufficient reasons to believe that the trial is nothing but a farce in the name of justice—one big circus.

The contrasting attitudes towards white and black are adequately portrayed by the writer. White women command respect, whereas a black woman is nothing more than a nigger. White men don’t lie but niggers are instantly perceived to be thieves. Witnesses, the judge, and prosecutor are corrupt and morally bankrupt while Paterson and his mother are emblems of moral strength. Dutt obtusely brings the reader’s attention to the work of Martin Luther king through the character of Leibowitz, who says that America is a kind of nation where white men fought for the black men. In fact, Leibowitz, to a large extent, is his interpretation of Martin Luther king.

However, the play is not entirely free of ambivalences that exist via the dilemma of characters like Joseph Brodsky and Leibowitz. The two, inspite of showing an ideological tilt towards communism and equality of whites and the Negro, are portrayed as helpless minorities in the courtroom circus. They repeatedly come across as incapable and dejected though the course of the trial.

Words like ‘propagandist’ and ‘revolutionary’ have been widely used as descriptors for Dutt. His strong communist ideology is pervasive in his writing. Through this plays, he resurfaces the scars of the Scottsboro trials through the eyes of a victim’s family in the ’60s. Through this time-leap, he establishes the immortality of the event in the colonial history of the blacks.

[Seagull Books; ISBN 9788170463313]