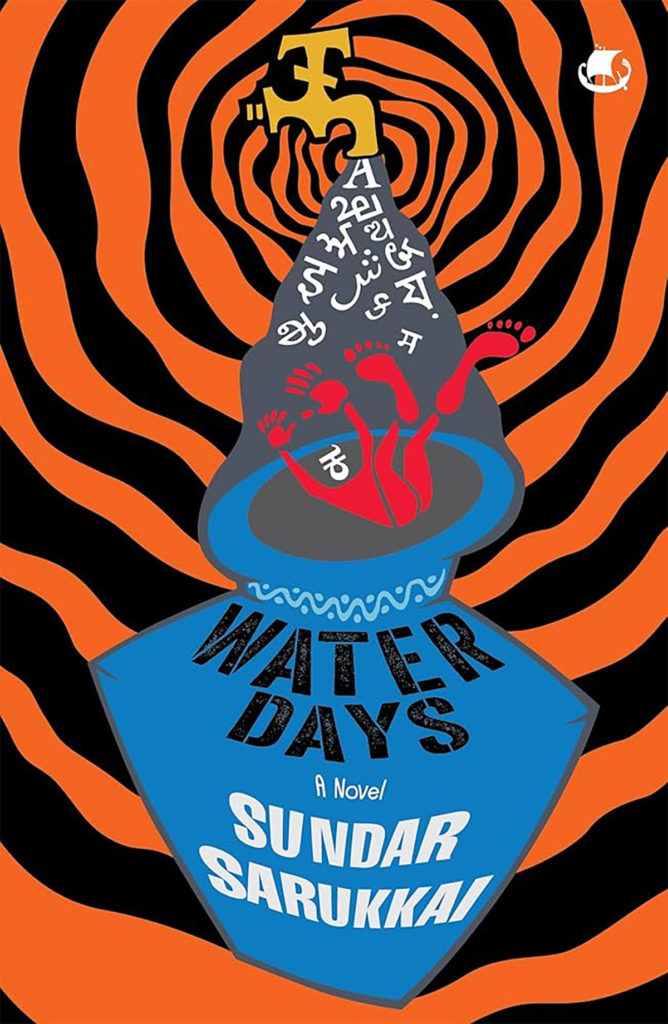

In Sundar Sarukkai’s Water Days, the millennium is fast approaching, and Bangalore is on the precipice of change. In Mathikere Extension, Raghavendra dreams of opening his own grocery store, but finds himself unable to extricate himself from a shady business partner. When a sixteen-year-old girl in the neighbourhood dies, Raghavendra and his wife, Poornima, find themselves in the middle of it all, tasked with uncovering the truth.

Water Days, Sarukkai’s follow-up to his debut novel Following A Prayer, is many things—a search for truth, a meditation on justice (and injustice), and a portrait of Bangalore in all its multiplicity. In a “pre-logue” to the novel, Sarukkai writes, “I recorded what the city told me… within these human sounds, perhaps there lies one true story of Bengaluru.” In this book, language feels alive.

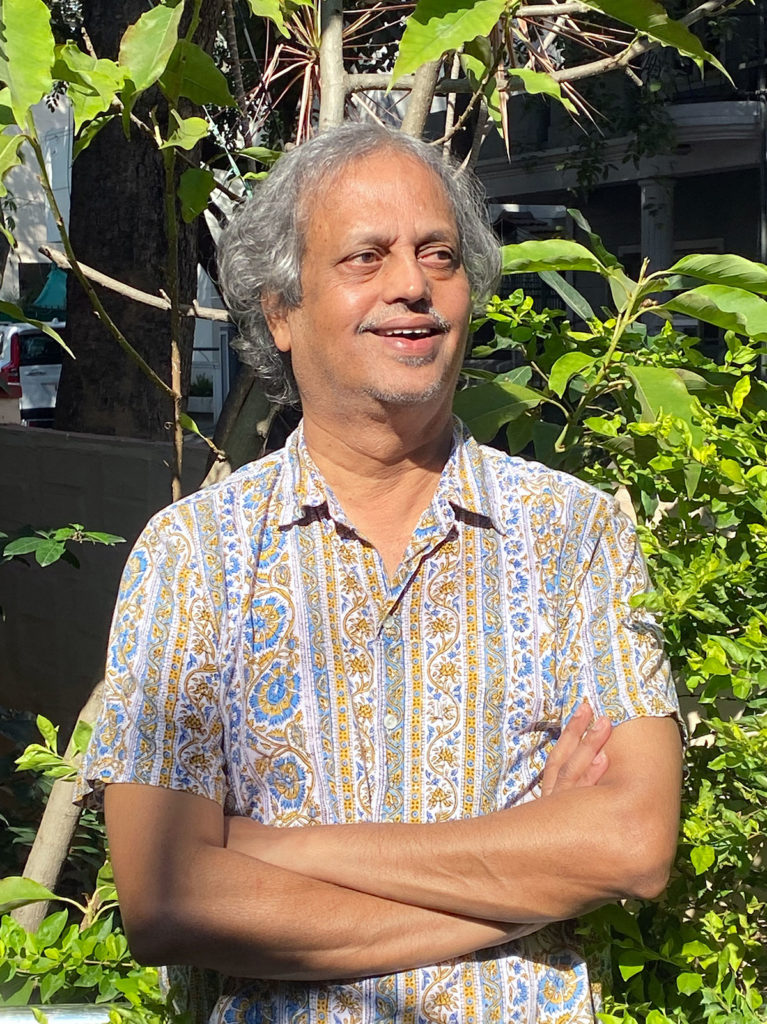

We spoke with Sarukkai about the novel, the philosophy present in the everyday, the languages that make up cities, and the wonder and joy of mysteries.

Water Days is set in late-‘90s Bangalore, a time that seems to have foreshadowed much of the city’s present-day reality. You’ve said you’re attempting to record a true story of Bengaluru. Could you expand on how you think about a city’s language?

The words Kannadigas, Tamilians, Malayalis, or Gujarathis have come to stand for cultural identity and not merely those who speak these languages. This is not surprising, since our nation is made up of linguistic states, and language offers the first framework for identifying differences. Today, in Bangalore, there is growing unease about the disappearing presence of Kannada in the public space, which is being replaced more and more by Hindi, leading to tensions that seem to rest on linguistic differences. Thus, stories of—and set in—Bangalore will have to engage with these dynamic linguistic tensions.

In asking what is the mother-tongue of a city, I am highlighting two aspects: one, how does a text written in one language, say English or Kannada, deal with this multiplicity, and two, is it possible to imagine the language of a city that is always more than the sum of the spoken languages in it? Since this story is about the everyday functioning of a community in a congested locality, it had to necessarily deal with people from different parts of India, most of whom are only trying to make a basic living and are not using language for other ends.

It is not a surprise that this spectre of language haunts Indian literature as well. With the growing availability of translations of Indian language texts, the old debate on the authenticity of Indian literature has resurfaced. The most important component of the authenticity argument is the link between a linguistic milieu and a story. Underlying this belief is the assumption that stories have their native language, that there is something called a Kannada or Tamil story. When these stories are written in another language, particularly English, there is the assumption that there is some inauthenticity involved.

This has become such a common assumption in this debate that its naivety surprises me even now, especially at a time when there is great value placed on translations into English. The authenticity claim depends upon the belief that a story has its ‘own’ language, a language that can ‘best capture’ the story. What does it even mean to claim this? A story is made up of characters as well as places; it is not a play which, in the traditional form, consists only of dialogues. The story is populated by non-speaking things, which also play an important role in the narrative. What is the language of the land, of the rivers and mountains, of the animals which enter into a story? What is the language of the things in the story? What is the language of a city that is not reduced to just talking heads?

How has this understanding shaped the way in which this story of Bengaluru came to life?

Bangalore adds another level of complexity. What should the authentic language of a story set in a locality in Bangalore be? People speak in Kannada but also in other languages. The land, the water taps and pipes, the cracked roads, the broken sewage produce their own sensorial language. And that is not Kannada! Nor other spoken languages. This is what I mean when I ask what the mother-tongue of a city is. So what is it to write in one monolingual register of a world that is multilingual, which includes the spoken languages of the people but also that of the world they inhabit? If at all one wants to push the authenticity argument, then they should demand that all our stories be written as multilingual texts, that is, books that will include different languages as part of it. That is why I believe that writing a story is an act of producing and discovering a language, rather than assuming that we have the readymade resources of ‘proper’ English to do it. This ‘proper’ English, too, cannot do the job.

When a writer writes about a city, she has to do things with the English language to make it yield the expression of the city. You have to mutate the language in order to discover the expressions of a place, but when we write in English we are often constrained by the possibility that our experiments with English may be seen as ‘mistakes’. What are mistakes for us is seen as creativity for ‘native’ English speakers (or should we say ‘monolingual English speakers’).

“What is the language of the land, of the rivers and mountains, of the animals which enter into a story? What is the language of the things in the story? What is the language of a city that is not reduced to just talking heads?”

Both Following A Prayer and Water Days appear, at first glance, to be mysteries, but both books may complicate a reader’s expectations of the genre, and become something much more questioning and complex. What does the genre or the idea of mystery mean to you? I’m especially interested in how your books engage with ideas of truth and justice, both important to the mystery genre, and how these shape your approach to endings and resolutions.

I find the enormous fascination with the genre of mystery to be mysterious in itself. I sometimes feel that this is a reflection of the leisure that accompanies the act of reading such books. There is a fundamental impulse in humans to search, to discover, to explore. All our disciplines are actually like mysteries. They search for some missing truth; knowledge, concepts, and ideas. Fiction is a search for missing stories. Mysteries in the conventional, popular sense today make the mystery element more obvious and in your face because every step is presented as such. So we have police procedurals that have become very popular but what they do is not just solve a mystery but also exhibit the method of doing it in explicit detail. Science too can be seen as a mystery story, resolving multiple puzzles and mysteries about the universe. It is not surprising that Edgar Allan Poe’s mysteries were deeply influenced by his interest in the science of his time.

You are absolutely right when you note that I complicate the genre of mystery. The mystery genre is the easiest way to keep readers interested. Conventional mysteries depend upon a clear articulation of the mystery and an expectation that a clear answer will emerge in the end. In Following a Prayer, there is a fundamental mystery—who listens to the words in a prayer? When I wrote that novel, I was, in a sense, trying to solve the mystery for myself. I could have done that as a philosophical text, but that would not have been as much fun as writing a story. Sometimes, there are no clear answers at the end.

Water Days began as an idea in the detective genre, but within a couple of pages of writing it, I knew I could not stick with its conventions. The world in which the story is set intrudes; it demands to have its say. The detective genre becomes infused with street life, neighbours, shop keepers, tailors, and most importantly family—in this case, the pervasive presence of a wife and two children.

With all these distractions, what is the fate of a mystery? That is the point that I am exploring in Water Days. Mysteries are not only about dead bodies or hidden treasures but also about our everyday life; they are not merely dark and brooding, but also the source of wonder and joy. In Following a Prayer, the story is about the mystery of language. How can we solve the mystery of how some sounds produce not just meaning but, in essence, a new world? How does this mystery sound through the voices of inquisitive young girls? In Water Days too, the mystery of language is an essential aspect. How do we know that we have found the language to tell a particular story? In both my novels, I stay within the genre of mystery in order to find some ‘solutions’. Another level of mystery in Water Days is that of patriarchy. How is it that these patriarchal practices have become so common that they can impact the lives of girls in such a drastic manner?

You mention writing to solve mysteries for yourself. I’m curious about how surprise, research, and curiosity itself play a role in how you write. How much do you plan or plot in advance? How does the story itself unfold to you?

I don’t think that I am a good planner in general, and definitely not of plots. Both in my fiction and academic writing, I let language and ideas take over without interfering in their journey. There is a displacement of my ego in the act of writing. That is the reason I don’t care too much for the reactions to what I write.

In Following a Prayer, I began with the basic question of where prayers go. The real plot there was to discover the world of the three girls and the narrative trigger was of a girl following a prayer to see where it goes. I couldn’t make much headway since there were too many different ways of dealing with this until I hit upon the image of the girl coming back after three days, lost in the mountains, but refusing to speak. Once that fell in place, then I just took a pen and started writing. I didn’t anticipate where it would go, didn’t know which characters would be needed, and most importantly, what the end would be. The only time I got stuck was with the ending. I wasn’t satisfied with the ending I had, until one morning when I got up with the image of what happens in the end. And then it was just a matter of a few days to finish it. This is not to suggest that this is all a mysterious process, since many of the themes in the novel were my preoccupation for many years. While it was not a plot driven exercise, writing was, nevertheless, a product of many sedimented ideas and images.

This was so for Water Days also, where the catalyst was not a question as such, but the world I lived in. It was a world that was begging to be written about. I respond very sensorially to places, to food, etc. I had vaguely heard that a girl had died somewhere in the locality. Years later, that sudden sense of feeling sorry at that moment became this story. It needed a visual, sensorial image as the background and collecting water at 3 a.m. became that. Then all else flowed, just like water in Bangalore taps, sometimes with a gush, sometimes murky and spluttering, sometimes only with the sound of air. I didn’t plot the story as much as I imagined living in the world of the novel and discovering something new with each page I wrote. In both these novels, I would say that I lived the life of the novels and through living in that world discovered what each new day would bring. Writing was perhaps nothing more than living in that fictional world as if it were real.

Something I love about this book is how language and silence often take a physical form. Words move like water; at one point a character complains about pickles and “the complaint was spread […] on the slice of bread”. This animation and movement with language is playful and evocative of how language is lived and experienced. How do you think about the experience of language while you’re writing, both when you write about it and in how you use it yourself?

You are right in that when I write it is often with a feeling about the language. Language is embodied and material in so many different ways. Sometimes the feel ‘with’ the language is more than that of the content or its meaning. Language has such a great power to manipulate our emotions, much of which begins from the very sounds of the language. The sounds of a language matter a lot to me. Perhaps that is also why I listen to a lot of classical music as I write, music that captures the essence of pure sounds. Languages have a relation to the place and time in which they are produced. That is the materiality of language, but each time we speak in English in Bengaluru or Chennai or Kozhikode, the ‘sound’ of English changes. Even the way our mouth is structured through speaking other languages influences the sounds we produce in English.

I like to think of the ‘scents’ of English as an image to capture the sensorial world of English when it is spoken in different parts. When English is spoken in Kerala, for example, the words travel with the scents of coconut oil and fried fish. It carries the feel of the sea and the swaying movements of the coconut trees. Are these descriptions too fanciful? Not at all. The point is to imagine language in this manner and then see how that transforms into written words.

Another embodied image of language that I often have is that of water, particularly waves on a beach. When you stand on the beach, water reaches you in waves, waves after waves. Sometimes they lap at your feet, sometimes swirl. Then there are currents that will pull you deeper into the water. Language is really like water. The words in a novel have the capacity to tickle you, hold you, smother you, suck you into their world. That is the feel of language that is most important to me as a writer. I want the words to speak to you, to touch you, to hold you in their embrace. I am not only writing a story but writing this language.

Writing seems to escape the accents and the scents of a spoken language, but a writer has the freedom to capture these sounds by playing with a ‘given’ English. Writing is the medium which produces authority, since it is through writing that one can begin to control and define what correct usages are. This is especially so for English in non-English speaking cultures. You have so many different styles and experiments with English in the U.K. or the U.S., but when we experiment, it has the potential of being declared as ‘wrong’. This pressure of writing English ‘properly’ does not allow us the freedom to pay attention to the way English begins to sound in the world around us. Perhaps this is the reason why quite a bit of Indian English writing sounds so British, so proper.

“You have so many different styles and experiments with English in the U.K. or the U.S., but when we experiment, it has the potential of being declared as ‘wrong’. Perhaps this is the reason why quite a bit of Indian English writing sounds so British, so proper.”

Water Days is a book about the ways in which we think and express in languages that we borrow or adopt; how we live between languages. It is a book written in English, for example, but many of its characters speak and think in many different languages, as Bangalore grows to accommodate more and more. You have previously spoken about translation and the “matrix of touch”, of two languages touching each other. How did that idea of translation (or communication between languages, more generally) come into play in writing Water Days?

Translation is an essential part of my writing, even though I write primarily in English. My first academic book was on translation in the context of scientific and mathematical texts. Since then, the question of translation—which has deep philosophical themes behind it—continues to interest me. In a keynote I gave in New Delhi for Bhashavaad, a national conference on translation (which you referenced in your question), I wanted to address a major misconception that has plagued the idea of translation—that there is always a gap when we translate from one language to another. This view has become so enshrined among translators and has led to various claims on which language is ‘better’ than another. One of the consequences of this is the view that English writing about Indian realities is potentially missing something. My writing, both in Water Days and Following a Prayer, was an attempt to produce a text that has the ‘voices’ of different languages in it, even though the written product is recognised as English. So one could see this as an already translated text.

In fact, I was deeply tempted to publish Following a Prayer as a translated text from Kannada. I think it would have been received differently, primarily by Kannada speakers. This is not a new idea; in the history of translation, there was a genre called pseudo-translations, which were basically original texts that claimed to be translations. My novels, in this sense, are not pseudo-translations—they are translations, except that the translation happens within me. It is a translation of speech to writing, where speech (the inner dialogues within myself, including that of the characters) may be in Kannada, Tamil, Hindi, or English. The reason why we do not think of this as an act of translation is because there is an assumed deliberateness in translating from an original text to the translated text. However, this is not the essential meaning of translation. In my keynote, I spoke about how language and translation have to be in a touching-touched relation, and how this view changes the way we think of translation. I see my act of writing—particularly fiction—as a simultaneous act of writing-translating. Another way to see this is as a pre-translated text, as an already translated text.

How do you see this play out on the global stage like when, for example, Heart Lamp wins the International Booker Prize?

Your question about Heart Lamp reminds me of the politics of the global world regarding translations of non-English texts. It is that the dominant English world can only accept mutations and modifications of ‘their’ English if they occur through translation. This is why it would be so difficult to get published if a writer not from the anglicised West wrote like Joyce or even in the language of black and Caribbean writers in the U.K. If we wrote in this manner, it would be a difficult task to get it passed by an editor—as much in India as elsewhere. If you write these mutations and modifications as a translated text, then it becomes acceptable.

Both my novels play with English to produce new sounds and forms, and it needs an open minded editor to allow this. I was lucky to have had V. K. Karthika as my editor, but it is not a simple task to convince mainstream publishers to take a chance on these styles. Copyeditors routinely try to sterilise a text so that it is ‘correct’, but according to which canon? While such constraints may be needed for some purposes, it cannot be a norm for creative fiction.

“I see my act of writing—particularly fiction—as a simultaneous act of writing-translating.”

If you look at the mainstream publishing of Indian English writing, by publishers both in India and abroad, you don’t see strikingly original texts. Is it that we are ‘allowed’ to do these experiments only under the excuse of translation? The praise for the translation of Heart Lamp is very important, but it seems to me that there is a bit of condescending acknowledgement that new idioms and sounds of English are allowed only because it is a translation. Even Bhasthi, the translator of this volume, says in an interview, “When one translates, the aim is to introduce the reader to new words.” Yes, but how does one introduce new words without the crutch of translation? Why and when do we need translation to produce these new forms of the language? Is it because writers in non-English societies are not seen as having a ‘right’ over English?

While it is great that Indian language texts are becoming globally accessible through translation, I wish the discourse on translation in India goes beyond the repeated clichés about translation, and instead engage in this project with more critical rigour and political awareness of both the nature of language as well as translation, such as can be found in the writings of Rita Kothari and Srinivasan Ramanujam, who have both engaged deeply with the theoretical as well as the practical aspects of translation.

I find the idea of writing a “pre-translated text” fascinating. You’ve talked about a lot of different ways to think and write about language here. I’d love to know if there are any writers, translations, or books that you think have used language in interesting ways?

I am doing something different in that my literary experiments are influenced by my philosophical perspectives but without being in your face. My first influence was James Joyce, whom I encountered as a teenager. My first short story, which was published in Deccan Herald when I was a college student, was deeply influenced by the freedom of writing that I imbibed from Joyce. But my basic interest is in detective and spy genres, and even here there are examples such as John Le Carré, as well as a plethora of international detectives whose personal life intrudes into their profession and vice versa. Most T.V. serials I see now have this kind of ambiguous, sometimes tortured, detectives. There are Tamil writers like Mouni, Puthimai Pithan, Nagulan, and more recently, Charu Nivedita, who have all been conscious of how to use, control, and play with language. Rushdie’s chutnification of English has led to various terms like Hinglish, Kanglish, Chinglish and so on. However, these coinages were more playful in nature, and most often did not arise from the kind of philosophical questions about language and of everyday life that really drove both my novels. In spite of all these attempts to ‘liberate’ English, mainstream publishing in India still tends to play it safe.

In your work with education, especially with children, you bring philosophy outside of the classroom and out of dense texts. What do you think is the usefulness of bringing it into fiction?

Firstly, I must say that I would hesitate to categorise my fiction as somehow bringing philosophical ideas into fiction. Philosophical themes are present in our everyday life and everyday actions. When we write about these events, do we allow these ideas to be explicitly articulated in the story? Too much of fiction has been reduced to psychological descriptions. It is rarer to find fiction that engages with the life of the mind, with the conceptual confusions of their characters. Some reacted to Following a Prayer by saying that children don’t ask such questions. They meant that village girls speaking only in Kannada could not ask such questions. I don’t know which children they have interacted with. Children ask far more difficult questions and it is the adults who don’t know how to respond to them. Did I use the girls in Following a Prayer as a way of discussing philosophy or teaching philosophy? Absolutely not. These questions arose as part of their everyday reactions to the world around them.

“Some reacted by saying that children don’t ask such questions. They meant that village girls speaking only in Kannada could not ask such questions.”

As the author, I do not bring in theories of language or religion into the innocent world of these three girls. Whatever philosophy there is in this novel, it arises from within these girls. It cannot be more than what these girls have the potential for—that was the challenge of writing that novel.

Why does fiction shy away from exploring in depth the cognitive and the reflective world of their characters? So much of Indian language writing is ethnographic; it is descriptive of social and psychological states but rarely explores the nuances of beliefs, thoughts, and arguments that characterise these states. So, to answer your question, I think that perhaps an exposure to philosophical thinking might make a fiction writer recognise those elements in the ‘ordinary’ stories of individuals. If so, then writing about those themes entirely within the context of the story is a literary move and not a philosophical one.

On the other hand, there are also attempts to explore the philosophical as the central theme through the mode of fiction. Here the philosophical dominates the story and the narrative, as in having historical characters who were philosophers. In both my novels, the philosophical does not assert itself and the story can only produce a philosophical space for reflection. In other words, philosophy exists in my writing not as a concrete presence but as a real and pervasive absence that has to be filled by the readers themselves. The philosophy you read in these novels is actually present in you, but catalysed by the text. As a fiction writer, I am merely a catalyst for your reflection and not a communicator of philosophical doctrines.