The square in front of the Kasbah in Chefchaouen comes alive in the evenings. As I arrived in the little-known Moroccan hillside town with my parents that afternoon, I had taken a quick look around the square, known to the locals as the Outa Hammam. Most shop fronts were drawn shut; empty plastic chairs sat fading in the steely autumn sun. The Kasbah—a fifteenth century al qasr, or castle, which now houses the Museé de Chefchaouen—was closed, stray dogs lolling at the entrance in the shade of a tree. It was Friday, a customary holiday in many predominantly Muslim regions.

Chefchaouen is a tiny town nestled in the Rif Mountains outside Tangier. Photograph by Neha Chaudhary-Kamdar.

When we stepped out later in the quest for sliced bread—my dad, an avid traveller, has remained rather inflexible about his food habits—we weren’t expecting the Outa Hammam to be swarming with people, their voices rising like the frenzied chirping of birds settling into a tree for the night. Locals selling antiques and fossils lined the lane leading up to the square, an old man bending over his display of cephalopods so he could haggle more efficiently with a group of tourists. Further into the Outa Hammam, a pottery store displayed brightly decorated miniature tagines at its entrance, the conical pots balanced precariously atop one another to form a honeycomb-like pattern. Next to this was a large grocery store, its bins of fruit and rows of biscuit packets bringing to mind the kirana shop my mother still uses in Hyderabad.

The store, however, wasn’t the only thing that transported us back home that evening. In the heart of the Outa Hammam, where the tourists went to eat, restaurant managers had arranged for musicians to perform for the guests. As my dad looked over the fossils, the tagines, and the baskets of fruit, I was distracted by the music, accompanied by the ebullient humming of what I immediately identified as a Shah Rukh Khan song. “Come, come, please,” a man standing outside one of the restaurants said to us, waving a menu softened from wear. “You from India? Shah Rukh Khan? Yes? Kareena Kapoor? Le ja le ja, soniye le ja le ja!”

This invocation of Bollywood wasn’t entirely surprising. Since our arrival in Morocco, many locals conflated India and Bollywood in their interaction with us. Technically, it began before we had even set foot in Morocco. On the hour-long ferry from Andalucia, Spain, to Tangier, Morocco, our passports were checked by a Moroccan border patrolman the moment we crossed the international maritime border. I was nervous as I stood in line for this check: while our visas were all in order, I couldn’t help but notice that the travellers a few places ahead of us in the queue had got into what seemed like a heated discussion in Arabic with the immigration officer. When our turn arrived, I reached for the dregs I’ve retained from my college French lessons, since that was the only language the agent spoke besides Arabic. I conveyed to him what I believed to be all the relevant details about our trip: I was a writer; we were tourists; the silver-haired couple with me was my parents.

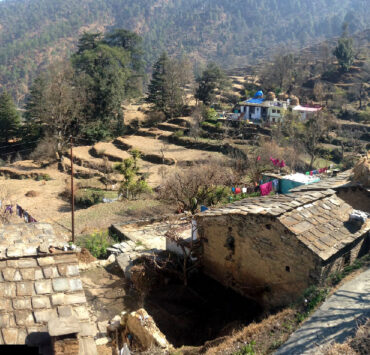

Combined with the views of the Lower Rif Mountains, Chaouen compared, to the author’s mind, with hill towns like Mandi or Dalhousie in north India. Photograph by Neha Chaudhary-Kamdar.

The man looked over his nose at our passports. “Vous-êtes Indienne?” he asked.

“Oui,” I replied; yes, of course we’re Indian. Our passports are in your hand.

A smile appeared on his face. “Tere liye?” he asked. “Veer-Zaara?”

“Yes,” I ventured cautiously. “Veer-Zaara, yes?”

He spent the next few minutes telling us that Veer-Zaara was his favourite film; that he loved Bollywood because unlike anything else he had watched, Bollywood films could be enjoyed with his entire family; and that Shah Rukh Khan was his favourite actor. Ignoring the people shuffling in line behind us, the officer began to sing the song Tere Liye, his “words” a close approximation of the Urdu lyrics he believed he had memorised. He paused when he was done with Veer’s lines, then looked expectantly at me. I froze—I must have misunderstood, he couldn’t possibly be asking me to sing Zaara’s part of the chorus. But my mother—the dignified lady with salted hair and travel-weary eyes—joined the duet without missing a beat. I stared at the tableau in disbelief, my mother singing a Bollywood number with a Moroccan border patrol officer. When he finally handed us our stamped passports, the officer asked me what “tere liye” meant. The joy that bloomed on his face when I replied made me want to hug him.

I don’t usually react this way. When you live in a predominantly white country for a while, you start to bristle when people talk about aspects of your culture in ways that seem reductive or that strip it of context and treat it like a consumer commodity. (Besides, I have learnt to be wary of Shah Rukh Khan. The first time I unexpectedly encountered someone fawn over him, it was two local girls in Cusco, Peru. I was a greenhorn then and I allowed myself to be carried away, only to realise later that the girls were also expert pickpockets. So while I love Shah Rukh Khan as irrationally as the next person, he did cost me a flip phone and some loose change.) Somehow, talking to Moroccans about Bollywood—or having them talk to us about it—didn’t feel affronting in the same ways. In every city I visited in Morocco, it seemed as though the locals couldn’t go fifteen minutes without talking about Bollywood and I was taken aback by the mellowness of my reaction to this. I was judging the reduction of “Indian” to “Bollywood” by Moroccans differently from the way I judge similar tendencies among westerners, where Bollywood is often replaced by yoga, “curry”, or Hare-Krishna Hinduism. The Moroccans’ interest felt more authentic, and I hadn’t fully worked out why.

Chefchaouen is a tiny town nestled in the Rif Mountains outside Tangier; I stumbled upon it accidentally while researching things to do around the port city. It was established in the fifteenth century as a fortress to protect against the Portuguese onslaught and the original settlers were Moors, Jews, and people from the Ghomora tribe. Today, the modern, urbanising sprawl of ‘Chaouen’, as the locals call it, resembles any of several small towns in developing nations: plenty of construction activity, a park with families relaxing on the lawns, uneven roads, A.T.M.s everywhere. Combined with the views of the Lower Rif Mountains, Chaouen compared, to my mind, with hill towns like Mandi or Dalhousie in north India. The part of Chaouen that transports you to another world is the medina—the old center—which, like most historic Moroccan cities, is preserved in pristine condition from centuries ago. The Chaouen medina shares its labyrinthine streets and clustered houses with the medinas of other Moroccan cities like Fes or Meknes. What sets it apart is that every single part of the Chaouen medina—doors, ceilings, stairs, walls—is painted blue. No one seems to know for certain why this is. Some speculate that Jewish refugees in the early twentieth century chose the colour because it was meaningful to them, others suggest that the colour simply repels mosquitoes.

Every single part of the Chaouen medina—doors, ceilings, stairs, walls—is painted blue. No one seems to know for certain why this is. Photograph by Neha Chaudhary-Kamdar.

While the medina is still home to a few families that have lived there for generations, large parts of the architectural preservation are merely cosmetic. Entrails of the once-clustered houses have been gutted and revamped into boutique hotels for tourists; craftsmen hawk Berber carpets and jewellery in every store, warning against escalated prices in bigger cities like Marrakesh. Tourism in Morocco runs like a well-oiled machine. Later, as I travelled further into other parts of the country, I couldn’t help noticing the polish and uniformity with which craft cooperatives presented themselves, their wares, and their culture to tourists. The Kingdom invests heavily in tourism and those working in the industry exercise a representational rigour befitting cultural ambassadors. In the warren of the Chaouen medina, however, the practised spiel of salesmen slips at the sight of an Indian family. The polite small talk and interesting historical tidbits that tourists are offered as a hook at the end of a fishing line are instinctively replaced by the effusive praise of Shah Rukh Khan or Amitabh Bachchan, and a warm familiarity towards you for hailing from the same part of the world as these demigods. Gone is the professional veneer and genteel sentences reserved for European tourists. Most people immediately wanted to know more about us and what our lives were like.

This sense of engagement is perhaps this is why I found myself less inclined to take umbrage at people in Chaouen conflating where I come from with Bollywood than I would in a comparable situation in, say, America. I wouldn’t assume for a moment that their love for Indian movies gives the Moroccans I encountered a particularly deep understanding of Indian plurality, or that Bollywood’s superficial cultural skimming could present a meaningful idea of India in the first place. Even in their enthused engagement with us, I recognised the desire to confirm their idea of what an Indian life must be like.

Still, when I think back to the border security agent who talked to us for several minutes about his family and about where we come from—despite the fact that we had practically no shared language—I see an attempt to establish some sort of commonality in the most unlikely situations. That night in the Outa Hammam, when my dad finally abandoned his quest for sliced bread and agreed to try some Moroccan khobz with a hearty tagine, it was because he was amused enough at the spectacle of a burly young man waving a menu at him while attempting Kareena Kapoor’s moves in Le ja le ja. For all its breathtaking beauty, Chefchaouen presents the challenge of navigating through a completely unfamiliar culture, history, and language. And while running this gauntlet is one of my favourite things about travelling, every once in while it is fascinating to see a point of entry open up into a different culture in the most unexpected of ways.