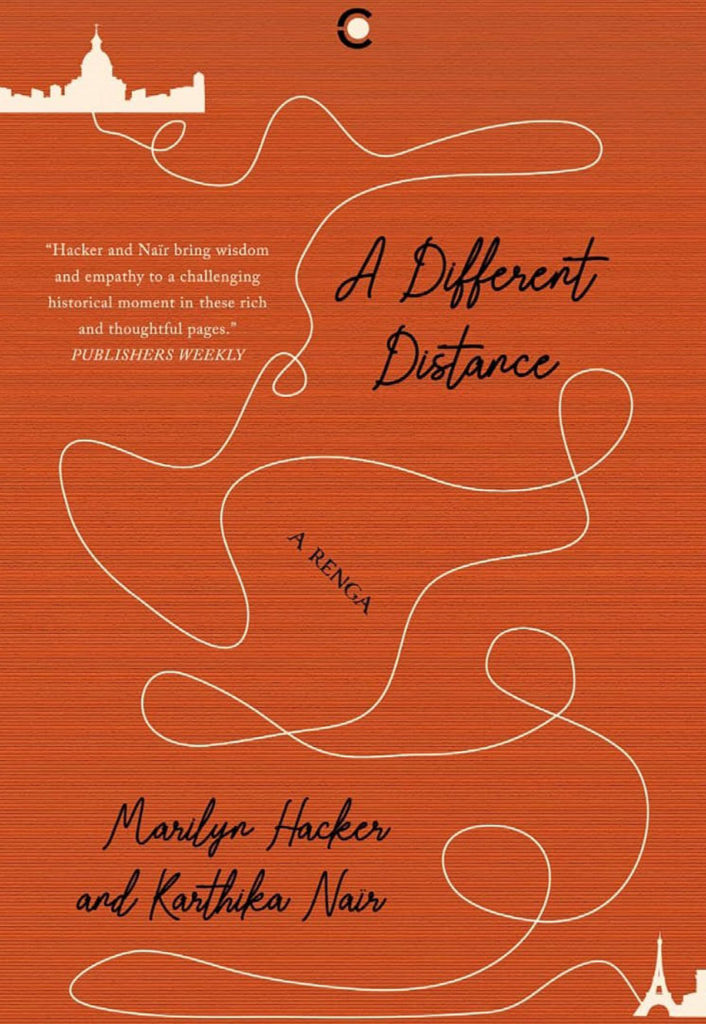

In 2020, as the world went into lockdown, poets Karthika Naïr and Marilyn Hacker found themselves isolated from their surroundings and each other—despite being in the same city. In this strange new world, Naïr and Hacker decided to start a daily practice—writing renga, a Japanese form of collaborative poetry, over email. Naïr likens the form to the game of antakshari, each new poem taking off from a word or syllable from the previous one’s ending. What emerges is a vast, linked poem, spare in its syllables, and both specific to the poets’ experiences and universal, a beautiful record attempting to make sense of a time that was destabilising for all. In these poems, isolation and community exist side-by-side, evident in the ways in which these poets speak to one another.

The result, A Different Distance: A Renga, was published in the U.S. by Milkweed Editions in 2021. Now, four years later, the book reaches us in India, in a new edition published by Context. Karthika Naïr and Marilyn Hacker answered our questions about A Different Distance over email—a fitting medium for a book that was borne from that very same method of writing.

A Different Distance is such a beautiful book, and it was most striking for me in how vivid the world it conjures is—a world that seems both a lifetime ago and like it just happened. What has it been like for you both to have this release in India so many years after it was written, and at a time when we’re “out” of the pandemic in some way? How do you look at it now?

Karthika Naïr: The U.S. edition of A Different Distance was published four years earlier, in December 2021, when we were still in the later stage of Covid-era restrictions and precautions, when travel was very much predicated by Q.R. codes of vaccinations, and the world divided into yellow, orange, and red zones. In fact, for the first nine months, all the book-related events we did were online!

The Indian edition means so much, all the more so because India is very present in the book, the way an absent love is never far from the mind: for two years, like many others, I could not travel to India, but conversations with kith and kin, news reports, all continued in real time (and are documented in the book). It has been hugely gratifying to see the Indian edition of the book become a reality. This has arrived three years later, when—at first glance, at least—the world seems to have moved on. But, as I realised during interactions with readers through the book tour in January 2025 organised by the French Book Office in Delhi and our publishers at Context/ Westland, we have all been marked by the losses and the radical changes that flooded those years, and those scars remain fresh: there is no family untouched by grief, no city without casualties. And at each event, people shared their own stories, stories of heartbreak and hope, solidarity and solitude.

Marilyn Hacker: As Karthika noted, when the book was published in the United States, at the end of 2021, we—the world and the two of us—were still living with many of the restrictions of confinement and fear of infection. To see this beautiful new edition now makes the experience vivid, alive again—not the fear of infection by the disease, to which each of us was particularly vulnerable, but the pleasure of collaboration, the impetus to write, to make something concrete of each isolated day. A reason to get up in the morning! To re-read it now is to experience again that welcome energy. The new edition’s existence, following the American editor’s enthusiasm, several years later, reifies my/ our conviction that we were doing something more than getting through another confined day. I learned a lot from Karthika—for example, I listened to Iqbal Bano playing and singing the verses of Faiz numerous times because she’d referenced it. And it entered my response.

“India is very present in the book, the way an absent love is never far from the mind.”

Structure and form—and experimentations with both—are something both of you are drawn to in your poetry. How did the constraints of both the form and those caused by the pandemic influence how you approached these poems?

Karthika Naïr: The biggest constraint to the renga we wrote was pandemic induced: the inability to meet! The renga—through the centuries—has been marked by the premise of shared time and space: whether in a monastery, court, or garden, the sessions were defined by a gathering, the presence of a group. And there we were, in our respective apartments, unable to leave our neighbourhoods, to sit around a table and write.

And though we were just five kilometres or so away from each other, the immediate realities of our respective environments were also quite different, which is indicative of how even neighbourhoods felt like distinct planets during that time!

At the end of the day, the inherent rigour of the renga allowed us to parse our concerns or experiences, and focus on the highlight of a day or an experience, and share it through the correspondence.

Marilyn Hacker: In a (perhaps) paradoxical way, the form and structure were liberating to me just because they informed my choices: they gave me a place to start and finish each tanka-response to Karthika, if only in the choice of repeated word, for each starting point, and the termination the syllabic/ line framework required, often with, in the back of my mind, the desire to end with a line Karthika might pick up, in response or counterpoint. The constraint of the pandemic was, on one hand, not so different from any collaboration undertaken at a geographic distance—but we were artificially separated. We could have walked to each others’ homes in an hour; we could have met midway; but we couldn’t—we were experiencing and exploring something similar in our very different lives.

You’ve both engaged in collaborative works before. What was different about the effort of collaboration this time, in the actual writing of these poems? I’m wondering how the experience of the pandemic influenced your writing in a way different from previous collaborations.

Karthika Naïr: For one, the regularity of the exchange: we were writing with far greater frequency than in my previous collaborations. Also, all the previous collaborations (whether on the page or the stage) were thematically circumscribed—we were writing about the urban rail networks, or narrative around Bangladesh, or, or, or—whereas there was complete freedom regarding content, this time. The rules or constraints were only predicated by the formal structure of the poems, but we were “talking” about whatever thought occupied our respective minds on a given day: a memory, fear of infection, a painful chemo session, a chat with kin, a dance performance, the explosion in Beirut, an air crash in Kerala, refugee camps being demolished in Calais…

Marilyn Hacker: The other collaboration I worked on was also at a distance, a significant geographical one, with the Palestinian-American poet Deema Shehabi, who lives in California. It centred on, yes, differences, in particular, the Palestinian diaspora experience in many places—a lived experience for Deema, while more a recounting of other peoples’ experiences, told to me or read about, and my interactions with them, for me. But, when not working on this, we were both free to go about our separate lives. We’ve just a few months ago written another exchange, about Gaza .

“These poems are about what mattered most at that given moment.”

I’m always curious about published diaries and diaristic poetry, and books like these that are a record of a specific time. All diaries are selective, which means that the memory or record of that time is selective. And then, of course, these poems are spare and tight, narrowing even further. What was that like, to zoom in to a moment or a feeling? How did you think about what gets left out of this particular record of time, in these poems?

Karthika Naïr: Something will always be left out, even in the most exhaustive or meticulously detailed of memoirs. In A Different Distance, it’s actually the converse: it was much more a process of distilling the day into the one, dominant, or remaining thought or memory: whatever seemed most immediate at that moment (since we were writing in real time, and never changed the “entry” of that day afterwards, except perhaps a word or a line break).

These poems are about what mattered most at that given moment. A lot of other things would have happened the day my colleague Ron died, and they were important too: I might have gone to hospital, had treatment; I definitely called a host of colleagues and friends to let them know, spoke to other friends… but those instants in the poem—the moment Larbi called me to inform me of Ron’s passing, the text message from Ron’s husband comforting me—were the ones that accompanied me into the day’s writing. They were the ones that shaped that day. On another day, when the political news was grim and unnerving, Iqbal Bano’s rendition of Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge was what I had on a loop, for solace, for courage. And I wanted to document that, just the experience of listening, or what Faiz’s words had meant to me, since childhood.

Marilyn Hacker: Poetry is meant to “condense”, but this was condensation taken to an extreme. I was possibly more isolated than Karthika was, and I hope she knows what a lifesaver the renga was for me. I had been in Beirut, with a year’s chair at a university, discovering a country and city I already knew I loved, and when classes stopped, and everything closed down, I flew back to Paris leaving everything behind—thinking over-optimistically that I’d be back in a month. I finished teaching my class by email, not even Zoom (I’m a computer dinosaur). Back in Paris, a city that’s usually so sociable, I didn’t know what would come next—nobody did. The chosen isolation that makes writing possible wasn’t so generative when it was forced. But that wasn’t something on which I wanted to focus, and having an interlocutor helped me center the moments of connection and joy—trees budding, a walk with a friend by the river, even going to the supermarket—that reified the conviction that life was continuing. And it was a vital connection to someone else’s life, Karthika’s, as well.