I received a link to this beautiful poem a few days before I was due to visit Delhi, my hometown, to spend Diwali with my family. Reading the poem transported me to my childhood and I was overcome by an urge to run towards our terrace. And I did. Only this time, instead of the familiar feeling of liberation that I associated with terraces, I was met with an extreme sense of isolation, coupled with an unfamiliarity that I didn’t expect to encounter in a space that had always been the most comforting and welcoming part of the house I grew up in.

I currently reside in a 500 sq. ft. apartment in Mumbai (a luxury and privilege that I have only now started to acknowledge), in what is called an ‘old’ building here. All three of its storeys are constantly being eyed by multiple developers to be razed for redevelopment into a high-rise apartment complex. My flat is on the second floor, with the building’s terrace accessible to me through the day. When I moved in three months ago, I was extremely excited about the terrace, and made instant plans around rekindling the lost relationship that I had shared with terraces in my formative years. Since then, however, I have only been to the terrace twice and neither of the visits have been anywhere close to ideal.

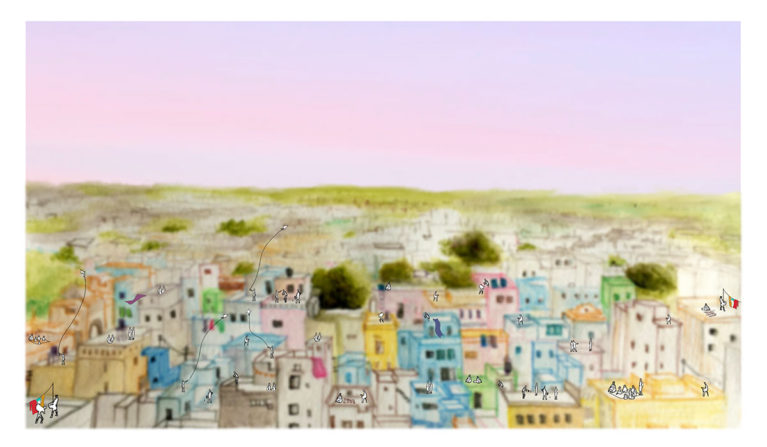

When I looked out from the terrace during my first visit, I saw no lovers trying to communicate between translucent sarees, no children playing ghar-ghar, no uncles gossiping under that garb of discussing world affairs, no aunties sun-drying potato chips—wherever I looked, I only saw concrete and glass staring back at me. I had forgotten that a terrace cannot exist alone. A terrace needs other terraces around it—without that, it remains an uninspiring and empty structure made out of bricks, concrete, and mortar.

There are no terraces in Mumbai; even the standalone houses referred to as bungalows don’t have them. It is difficult to explain my extreme love for terraces to people who have grown up in this city, though it is hard to blame them for their lack of terraces—tropical climates with high rainfall require sloping roofs for the water to drain quickly. Terraces, even ‘water-proof’ ones, end up collecting water on rainy days, which eventually seeps into the rooms below. Unlike in the north of India, where we use terraces to soak up sunlight during the winters and sleep under the stars during the summers, Mumbai stays hot and humid all year round and its heavy, unpredictable rains leave terraces unusable for at least four months in a year.

Our terrace turned down no-one.

My family’s house on the outskirts of Delhi was built on 900 sq. ft. of land bought by my grandfather in the late ’70s, when the cost of construction used to be much higher than the price of the land. The house has been rebuilt multiple times since then to accommodate our growing family. The low-rise neighbourhood has mostly comprised of two-storeyed houses with abutting terraces. In the past five years, however, most of the houses around us have been rebuilt into five-storeyed multi-apartment buildings—some to accommodate the rising population and others to accommodate the developers’ greed. My father and uncle didn’t want to be left behind and decided to embrace the trend.

By the time I was born, the house had changed shape and form at least five times, but it was never fully demolished until two years ago, when my father and uncle decided to build an apartment complex on the family land. Before the demolition of the house began, I went up to our terrace one final time to say goodbye to my silent yet solid companion—one that saw me through a rebellious childhood and a relatively calmer adolescence, one that would soon cease to exist outside of my memories. The terrace was no longer what it used to be—the sheesham tree that used to shade it was long gone, replaced by a cold concrete wall. I could see that the terrace was struggling to make sense of its surroundings—just as I was—and in that moment, it made sense for it to go away, rather than be cursed to a life of irrelevance.

We were a family of 10, and there was a constant flow of relatives and friends who were always lingering in our courtyard or the baithak (a sort of public drawing room). There were always urgent matters to be discussed and gossip to be passed over steaming cups of chai in the winter and cool glasses of roohafza in the summer. The entrance gate of our house that opened into the courtyard was always open and would only be bolted for a few hours in the night.

I have always thought of my home as a public space because none of the rooms would ever be empty. I shared a room with both of my siblings and it was only when I turned 23 that I discovered the joy of having a room of my own. Every wall in the house was an avid listener and talker, so I often retreated to the terrace, where there were no walls to reflect my thoughts and words—they were safely absorbed by the expansive sky. The terrace was the only ‘private’ space where I could think, cry or sulk without being bothered or questioned.

It wasn’t just me—every other person under the roof of our house looked towards the terrace for their own moments of solace and secrecy. The rules of engagement on the terrace were different from the rest of the house, and understood by all its residents: on the terrace, we left each other alone unless we communicated otherwise. Any matter that had to be kept away from the grapevine was discussed and dissected on the terrace. It was the terrace where I broke the news of having my first period to my father. It was the terrace where I cried away the night after my dog disappeared and my cat was found dead on the street. It was the terrace where I told my mother about the boy I was madly in love with. I remember the terrace of my home as boundless and infinite, where tears were shed, hopscotch was played, slices of raw mango were dried, and assuring glances were exchanged across the streets.

Our terrace turned down no-one. It was a living paradox, both public and private at the same time. Even though it was the only private space I had, I had no special access or rights to it. There were no doors or walls to hide behind in the terrace, and yet I could always find solitude and hide from the world.

Apart from hosting my inner dilemmas and heartbreaks, for me, terraces were also vibrant community spaces. Terraces were where kites were flown, teenage romances bloomed, grandmothers lined up children to remove lice from their hair, and all kinds of happy, sad or bizarre pieces of news were shared haunched over the parapets. I can hardly remember the interiors of my neighbours’ houses but distinctly remember their terraces. In our neighbourhood, we seldom went to neighbours’ houses for dinners or lunches, except for awkward birthday parties, but terraces needed no invitations.

Maybe terraces are not functional anymore in an increasingly commodified world, where more and more people need to fit on to ever-shrinking pieces of land. In the last decade or so, I have seen them quickly disappearing from Delhi. Apartment complexes are replacing low-rise neighbourhoods, and even people with private residences (like ours) are converting their single-storey homes to multi-floor buildings that can be rented out to make more money. Terraces seem like a small sacrifice to make in the face of this rapid development, and balconies are now presented as the alternative to terraces. Seriously, who are we kidding?