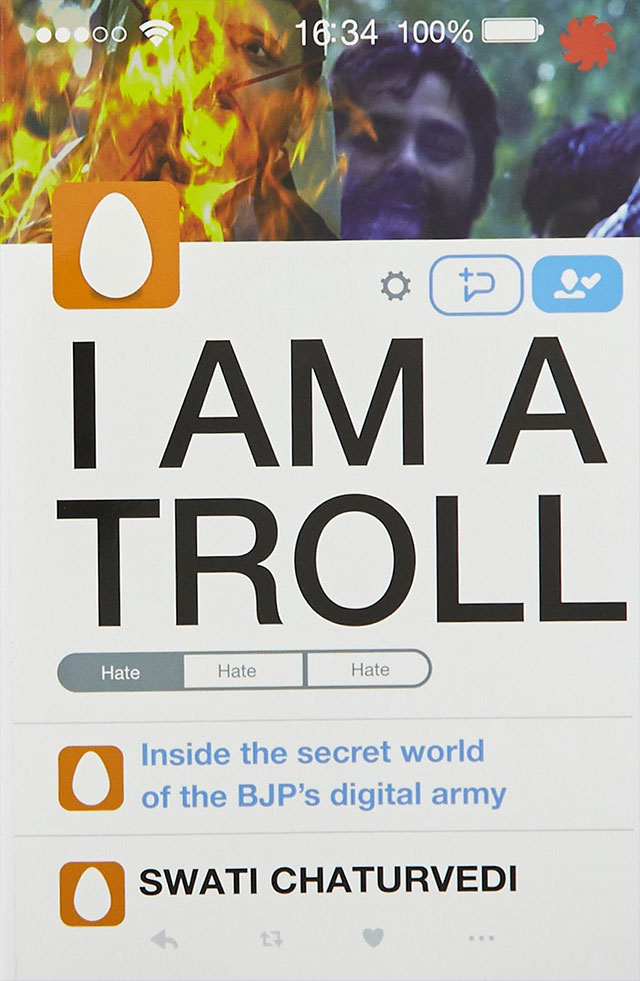

Swati Chaturvedi, in her introduction to I Am A Troll: Inside the Secret World of the B.J.P.’s Digital Army, lays out her professional background and experience as an investigative journalist who has been fighting hard for her freedom of expression, while also being at the receiving end of vicious and slanderous online trolling. She goes on to describe trolls as “the goons of the online world” belonging in the Indian context to the Hindu Right-wing and professing highly nationalist views. Her frustration with the lack of police sensitivity or support for sufferers of troll-harassment is what prompted her to turn her journalist’s eye towards deeper questions about the identities of anonymous trolls, their link with Prime Minister Modi and the ruling party, B.J.P., and the meticulous planning and organisation of this sinister activity.

Her engagement with this phenomenon, as a female journalist with independent political opinions, then, is a very personal one. In preparation for her book, she apparently spent two years meeting trolls, B.J.P., R.S.S., and Opposition leaders, government officials and bureaucrats, and I.T. cell chiefs of B.J.P. and A.A.P., the two foremost political parties with a considerable online presence. (A.A.P. I.T. head Ankit Lal, who has recently been engaged in a battle of words with current B.J.P. I.T. cell chief Amit Malviya, tells the author that although A.A.P. too uses similar propaganda tools like hashtag campaigns, the cell is composed entirely of volunteers and stops short of rape and death threats, unlike their rival B.J.P.)

The first chapter, ‘Blessed to Be Followed by P.M. Modi’, dives headlong into the mindboggling and well-known information that Prime Minister Modi (who is known to operate his official Twitter handle himself) follows several of these trolls despite the slew of F.I.R.s registered against them—the appendix lists these 26 accounts that regularly sexually harass women, make death threats at, and abuse Opposition politicians, journalists, and minorities, and spread conspiracy theories. In this and the fifth chapter, Chaturvedi lays out the shrewd use of the digital space by the R.S.S., with its “Internet shakhas“, and later the B.J.P. with its I.T. cell at its 11, Ashoka Road office. Both affiliated organisations feeling persecuted by mainstream “sickular presstitutes” capitalised on the huge opportunities that the digital world put at their disposal.

Chaturvedi traces this online hate-mongering to the coarse discourse of several B.J.P. ministers like Giriraj Singh and Anil Vij, for inevitably, “… if you peddle lies and violence online, what does it say about your behaviour in the real world?” In another chapter, the author refers to “forty-rupee tweets” that are being paid to agencies to attack anti-Modi individuals like Arvind Kejriwal, even though such mails have not been successfully traced. The author also remarks on the worrying frequency with which various government ministries and bodies (Culture Ministry, Digital India Project, All India Radio, Press Information Bureau) and senior B.J.P. politicians like Piyush Goyal and Rajnath Singh are tweeting out false claims, Photoshopped images, and hateful messages, even if this may be more a case of carelessness than deliberate deceit. But putting the hilarity ensuing from falling for parody accounts aside, the author highlights the far-reaching and dangerous consequences of such casual online behaviour. However, she also notes the more productive and laudable use of social media by the likes of B.J.P. Ministers like Maneka Gandhi, Sushma Swaraj, and Suresh Prabhu.

The most powerful component of the book is the testimony of former troll Sadhavi Khosla, a suave and well-off entrepreneur, whose enthusiastic involvement in the party’s social media campaign turned into a sudden and painful disillusionment that led her to cut her ties with the B.J.P. She provides significant insight into the systematic operations of the party’s social media campaign, its permanent combative stance, from meeting daily hashtag and trending targets, to spreading fake news and Photoshopped images, orchestrating hate campaigns, bullying and threatening corporate giants, etc. Khosla also provides the author with WhatsApp forwards from the then-active B.J.P I.T. Cell Chief Arvind Gupta with instructions about all of the above, and she testifies to the seriousness with which this work is closely monitored by the Prime Minister himself. One is reminded of the B.J.P. I.T. Cell founder Pradyut Bora quitting the party, with a four-page allegation about the undemocratic ‘madness’ that had come to drive the party’s functioning, an important thread Chaturvedi fails to pick up.

The strength of this slim book is its extended engagement with Khosla, and the elaborate report about B.J.P.-created Modi hashtags being operated from Thailand, investigated by Ankit Lal (reviewed and confirmed by independent technical expert Siddharth Bhaskar) and reproduced in the book’s appendix, even if the study is obviously politically motivated. Her interview with Ram Madhav, one of the influential General Secretaries of the B.J.P. and a seminal architect of the Sangh’s social media strategy, though, turns out to be less insightful and more evasive. Chaturvedi does not look for existing theorisations of this phenomenon in India or even anywhere else in the world. By way of suggested reading, she only includes references to three newspaper articles. The only other opinion piece she refers to is a rather facile newspaper column by author Chetan Bhagat, who describes Right-wing trolls as typically male, lower middle-class, sexually frustrated, and pro-Hindu, but also ashamed of Hindu identity, insecure about weak communication skills in English, and suffering from an inferiority complex. Chaturvedi concurs, adding that they are rabidly anti-Muslim and each of them “is the guy you would never look at again”.

This kind of simplistic social and physical profiling, summarised before the presentation of interviews with three trolls, smacks of the class elitism that she brings to the book. Such a stance, though possibly emotionally gratifying for a sufferer of online trolling and difficult to avoid in face-to-face interaction with one’s abusers, serves little towards understanding the equally big demographic of highly educated, eloquent B.J.P. members and supporters who cheerfully support and share the rabid views of these trolls. Though she protects their anonymity, she is transparently at a moral, though vulnerable, high ground while she is interacting with them.

Despite all this, hers is a worthy venture into the deep, dark world of Indian cyber-terrorism that should attract more detailed investigations and the placement of legal safeguards online. The book points to the need for all social media users to be critically alert about our sources of information, and the lies and hate rampantly circulating in the online world, forever ready to incite violence. The book gestures towards discussions about the larger role of the digital media towards the negation of nuance and dissent in popular discourse, and the polarisation of democratic societies. Though it was published two years ago, this book is frantically relevant in the immediate present, as evidenced by vigilante hacker Elliot Alderson’s tweets about third-party misuse of Aadhaar data, whistleblower Christopher Wylie’s allegations connecting Cambridge Analytica to the Congress and J.D.(U), the Cobrapost sting operation revealing mainstream and online news websites agreeing to publish propagandist Hindutva material, and the arrest of fake news peddler Mahesh Vikram Hegde who runs the website Postcard News.

This, apart from the several leaks of sensitive data—the C.B.S.E. Class 10 Board and Staff Selection Commission exam question papers, and the announcement of the Karnataka Assembly election dates by both B.J.P. and Congress and a few news channels before any official announcement by the Election Commission—are all good reasons to be very suspicious about digital media as new tools of hegemonic discourses and the urgent need of digital safeguards, like the ones mentioned to the author by former Chief Election Commissioner S M Quraishi. The author leaves us with the disturbing image of the growing “monster” that is the B.J.P.’s social media cell, attacking non-conforming and dissenting citizens, with inevitable consequences for the 2019 General Election in India that is barely a year away.

[Juggernaut Books; ISBN 9789386228093]