When Shakespeare wrote King Lear, he deviated from his source (Holinshed’s Chronicles) in two ways—he changed the climax from a happy one to a tragic one and he added the subplot of the Earl of Gloucester and his sons Edgar and Edmund.

In the Holinshed timeline of events, King Leir (Lear) is reinstated to the throne by his youngest daughter Cordeilla’s (Cordelia) army. King Leir goes on to rule the kingdom for two years after which Cordeilla takes over before she is finally overthrown by her nephews. In Shakespeare’s retelling, Cordelia and Lear die sorrowful deaths to make what is now known as one of the greatest tragedies to have ever been written.

If you lay down the spine of King Lear in Pixar-like fashion, it is the story of a wealthy, patriarchal monarch, who decides to give his kingdom to his daughters. The youngest daughter refuses to pander to her father’s needs, she is disinherited, mayhem follows, someone’s eye is gouged out, there is a storm, and lots of people die. However, to strip down a story to its bare skeleton without giving due regard to its holistic intent, social conditions, and pathos is unkind and ungainly.

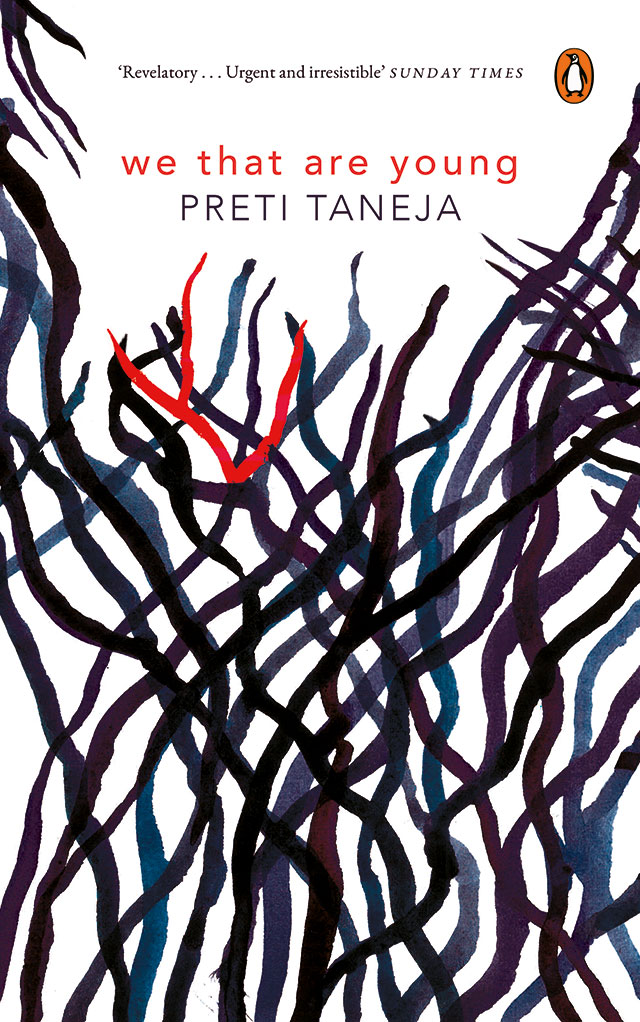

Adapted by Preti Taneja, and set in contemporary Delhi and Kashmir, We That Are Young is a modern-day, desi retelling of King Lear that was inspired by a sequence of events that originally took place in 847 B.C.E. Giving credit where it is due, the author, in retelling a widely adapted play, with its gender-based and power-hungry elements, made a good choice by setting it in Delhi. In We That Are Young, Taneja’s Delhi efficiently embodies the streaks of her story—sustained subterranean anger, abundant misogyny, and the superficial glory of unimaginable wealth.

“It took just three weeks to shut up America,” narrates Jivan, the novel’s Edmund, who returns to India to claim a share of “land, and not money” after the death of his mother. Despite living in America for over a decade, without as much as any connection to anything Indian, Jivan’s internal monologue is in Indian English, scattered with local Delhi slang. Not to mention, Jivan is extremely brand-conscious. “Jivan puts on his shades (Raybans, vintage),” and “His spare suit is Hugo Boss wool,” and he wears “an 88 Rue du Rhone chronograph Double 8 Origin”, and he drinks “black label (sic)”. If one makes concessions to the characterisation, it is as if Jivan is still clinging on to the version of himself who grew up in Nizamuddin, went to Gurugram to work in an Indian-version of Pierce & Pierce, and now he can’t help but think of how he is going to get himself some of Devraj Bapuji’s (Lear’s) inheritance because the Gurugram traffic is killing him.

When Jivan arrives, after a long drawn-out and tedious tour of the grounds where his father lives alongside Devraj Bapuji’s family, Jivan finds out that Bapuji’s youngest daughter Sita has left the house after refusing to proclaim eternal and boundless love to her father. All the members of the family and the subjects in Bapuji’s kingdom are subdued. “Don’t. Please. We cannot let a soul outside know what is going on. Not a whisper, not a single sound. Until I can fix it. Or it is done,” says Gargi, Bapuji’s oldest daughter, to Jivan, when he is sitting with her in a large, red, personal cinema theatre, itching to hold her hand, but making do with gazing at her body in minute detail. Gargi is the dutiful eldest who has spent most of her life trying to win the approval of her difficult father and sacrificed small pleasures in life all along to come across as the perfectly primed rose. “Even when a girl in her batch had leant (sic) Gargi a cassette tape of Alisha singing Madonna, she was not allowed to put it on.” And now, after spending Friday after Friday of her life reporting to Bapuji on how her sisters had behaved during the week, and painting a peerless picture of Sita, Gargi is furious at her youngest sister for having left the house in spite of following the script, marrying the man chosen for her, taking her share of the inheritance so that Gargi can get hers as well. And then, there is Radha, the party-animal version of Regan, who, quite honestly, is painted as a woman who wouldn’t know what to do with her share even if she got it. Radha is intertwined in her social life, living in royalty, having kinky-bordering-on-gross sex with her dominating husband, and then, consensual-sensual sex with Jivan, dominating him this time around. “His head is so solid, a coconut under her hands.”

The sections in the book alternate between the points of view of the three daughters and Jivan, each one of them having long internal monologues, secretly hoping to get the lion’s share of Bapuji’s company, aptly titled Company, and describing in painful detail the inner workings of the empire and those whose lives are stitched with it. The plot of We That Are Young follows the story-spine of King Lear perfectly, and then, a freak storm arrives in Amritsar one night, in which Bapuji goes missing and is found three days later. The daughters find out from the news reports that are splashed across newspapers all over the world, “even Dawn, for God’s sake, Dawn.” Overall, the story is predictable and tedious, and one begins to wonder what could be a better use of one’s time. It could have been engaging, had it been written well.

In the entire text, it is very hard to pinpoint the narrator of Taneja’s ambitious work. The third-person narrator, the first-person narrator, and the omniscient narrator are interchangeable. Following the plot, thus, becomes a chore and a conundrum all at once. The book is divided into five sections with multiple points of view, and a question readers may constantly find themselves asking is: who is narrating this story? Additionally, Taneja has written the book in what one might call extremely Indianised English. The book is generously loaded with Hindi words and local slang, so much so that it is hard to distinguish between an English-speaking omniscient narrator and the internal monologue of an Indian character, who thinks and talks in Hinglish. In some parts, it is hard to tell if the novel is being narrated by a schizophrenic narrator and then meanders into the mind of a stereotyped Delhi character and then, back again to the narrator. While this is not a bad thing, it just takes a long time getting used to (and not even entirely, at that).

In Maryam Mirza’s book Intimate Class Acts, she has dedicated a chapter to discuss the telling of postcolonial stories in the English language and whether characters can be given agency of self-expression when the language used is not theirs. In an essay on the subject, Chinua Achebe weighed the pros and cons of using a foreign language to tell African stories. Quoted in that very essay, James Baldwin says that one ought to make the English language one’s own instead of imitating it. In her book, Taneja seems to have made English her own, and how. While the language used may technically seem like a leap forward, it is up for debate whether it enhances or deteriorates the reading experience. While the inclusion of local slang, Hindi words and phrases may be a stylistic choice, the text shows that there was very little copyediting involved before it was published. Suffice to say, the book could have done with a lot of editing, copyediting, and a fresh pair of eyes by someone impartial.

* * *

“Who has our dearest Radha to manage, he says. Poor Bubu.”

“Now he is face to baldspot with Gargi’s husband, Surendra, in thick-rimmed glasses, an embroidered silk kurta.”

“I asked her where she wanted to go, and she said the Sunderbans, in the tiger infested mangrove forests and mudflats of west Bengal.”

* * *

King Lear is known for its themes of gender roles, appearance versus reality, generational conflict, hierarchical structures, and madness. The Bard’s play also uses metaphors of animals across the text. The setting of Taneja’s novel allows a peek into the intensely patriarchal and toxic relationship shared between the father and the daughters. And this is why, setting the novel in India seems to have worked for some readers, because it embodies the gender roles entrenched in Indian society such that the women in the novel have to find constant ways of building their self-worth because they are treated as second-class citizens. In King Lear, there are hints of reverse Oedipal behaviours, while in Taneja’s novel, the sexual tension is present on both sides, of the father and of the daughters, and very overtly so. As a confession to her father after returning home, Sita tells Bapuji in detail about her sex life back in the U.K. To a reader, it seems dissonant that despite the deeply patriarchal relationship shown, a daughter can speak so freely to her father about the sex she had. Taneja has also used animal metaphors across the book in a, let’s just say, interesting way.

* * *

“You girls are like two diseased owls, unnaturally taloned, freakishly beaked with your make up so much and your nails all painted. These things you think so beautiful do not cover your stink. Nari nari bohut hogaya, Sarkar mat bano.”

“He smells sweet—the way baby monkeys do after milk.”

* * *

In an interview at the 2015 New York Indian Film Festival, Professor James Shapiro of Columbia University and Vishal Bhardwaj had an engaging, insightful discussion about Shakespeare. While discussing Haider, arguably his best work in the Shakespeare trilogy, Bhardwaj said, “I always remain very true to the soul of the play rather than the text of the play.” Taneja has not only acknowledged Bhardwaj’s inputs for her book, but her character Sita also makes a passing reference to him in the novel when she is in Kashmir. The comparison of a film to a book is unequal, but it remains true that Haider was truly Hamlet in an Indian setting and it might well serve as an Indian benchmark for Shakespearean interpretation. All things considered, it is safe to say that We That Are Young is as far away from the soul of King Lear as modern civilisation is from 847 B.C.E.

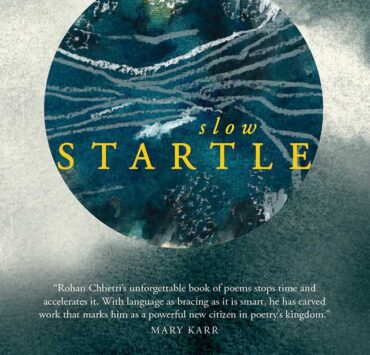

[Penguin Random House India; ISBN 9780670090464]