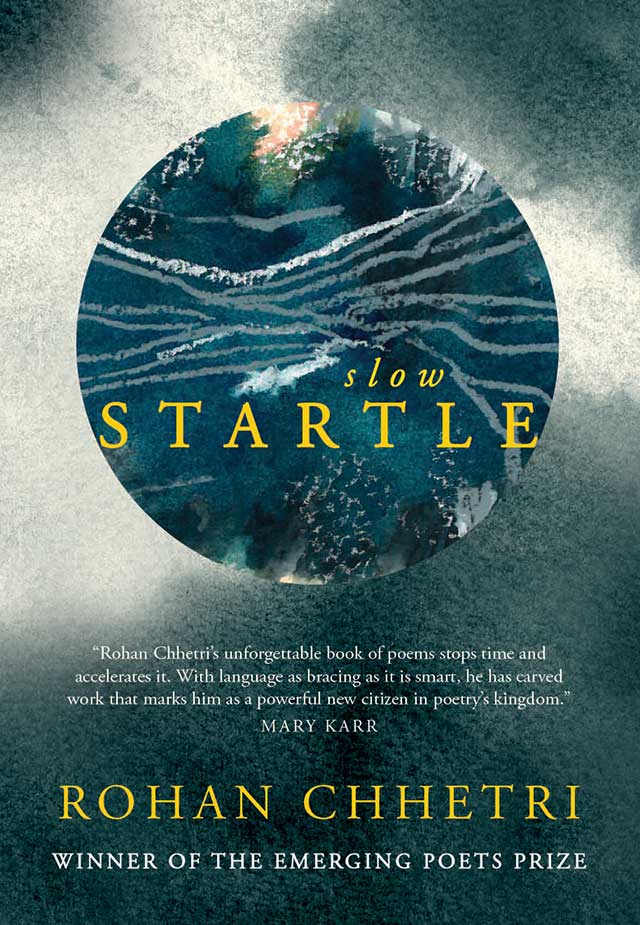

First off, Slow Startle is a book about death. Rohan Chhetri does not make any bones about it.

Chhetri’s poetic world is a hologram of memory, it shudders with a wind breaking on his face, and enters his poems (like violence enters his poems), they seem as though they’ve been written across a youth well lived (sometimes several childhoods, some beautiful, some rife with terror) that glow with beauty, with sensitivity, with contrition, and pain, poems that finally gain momentum, to settle, and slow-dance with a past interminably negotiated with the ongoing present.

The poem ‘A Difficult Mountain’ is a delicate portrayal of the speaker’s relationship with his mother, evidenced in the intimate uneasiness of never having money, or never having enough anyway, not even to visit her son. Yet, yet. Something even more private emerges—a clandestine conversation over the devastating family event: theft taking place as his mother was presumably alone. (In another poem, the speaker confesses that his father crosses the border to go to work.) The intensity of all the ‘what ifs’ in the speaker’s imagination, simultaneously looming over in his mind as he talks to his mother on the phone, like a black cloud, is physically palpable to the reader. This reveals a familiar proximity between mother and son, and is compounded by her confession about a dream, where she is climbing an ‘infinite’ flight of stairs, going up a mountain, constantly ‘falling short of footholds’, as he apprehends the dream (obviously) better than she does, afraid that she’ll ‘understand their immensities one day’. A palpable sigh escapes my mouth, in the end.

The tour de force in the text is, paradoxically, also the most tender. ‘Elegy to the Year of the Wood Sheep’ opens with a softness that it admits to at the very end of the first paragraph. It exposes the certainty of the speaker, as well as the poet, choosing perfect metaphors: a hair in his blueberry pie, pebbles smoothened over by the timeworn caress of water, his intention sharp in the opening, and deliberately dwindling as we go along.

This poem lunges at us punctiliously, as one finds that it is, perhaps, the most faithful to the poet’s voice. Chhetri neither claims nor aims to be older or younger than he is in the speaking voice; he confesses that there is an aspiration towards the romantic by alluding to the Romantics and their personal tragedies, even in and despite, his sombre articulations of death throughout the book. There is a seething sense of paranoid aging and imminent death, cautiously sitting next to poetry’s immortality, in this elegy. A carefully intended reference to the migrant starlings as he turns twenty-eight gathers in him an ‘unmirrored sentience’, the metaphor falling short for words, in describing the changing current of location, concomitant with time, that he attempts to (but can’t) recreate, or ‘mirror’ in recapitulation; a confirmed infancy—‘I was new here’. As poets tend to contemplate their own death, the speaker invokes Shelley at twenty-eight, missing his friend Keats, who died at twenty-five. A sorrow washes over the reader, if they have ever, even once, been touched by the humane, sweet, kindly words of either poet. This is what the speaker feels, too. All the way, until the end, struggling to remember (though aware of the impossibility of that task), to recall the language one cried in ‘at that first clamour of the universe’. Wondrous words, unfurling as they smoothen the abrasions, inflicted on us by the surgical invasion of existence.

Slow Startle begins by establishing the affective location of the speaker, who is an inward looking being, markedly and suddenly disturbed by news of death. Again and again. He might get used to it, but one never gets used to it. Never. At the end of the last poem in the book, he is ‘already wishing to return’. This desire might mean something in the poem, and an entirely different thing as it is said at the end of the book.

To gather some insight into this collection of Chhetri’s poetry, one must meditate on the Hindi word ‘Thehraav/Thehraao’. There is no holistic translation that comes into mind. At first, the word ‘restraint’, is followed by ‘quietude’, then to ‘stillness’, go ahead and flit between ‘gravitas’, ‘equipose’, ‘composure’ and arrive at ‘observant mindfulness’. All are good adjectives for Chhetri’s work. There is a searing, riotous, and yet a calm ordinariness that is apparent at the fore.

There is perhaps, one complaint: the themes are a tad repetitive. In the construction of a book, one retrospectively arranges the poems in a way that may carry the reader through the text at a digestible speed, but that means a certain sense of a forward movement, a progress. If grief is grief, then poetry is poetry. This, however, does not do any damage, which is brilliant.

Overall, Slow Startle is a wondrous book, the gift of 2016 to Indian Poetry in English.

[The Great Indian Poetry Collective; ISBN 9780986065248]