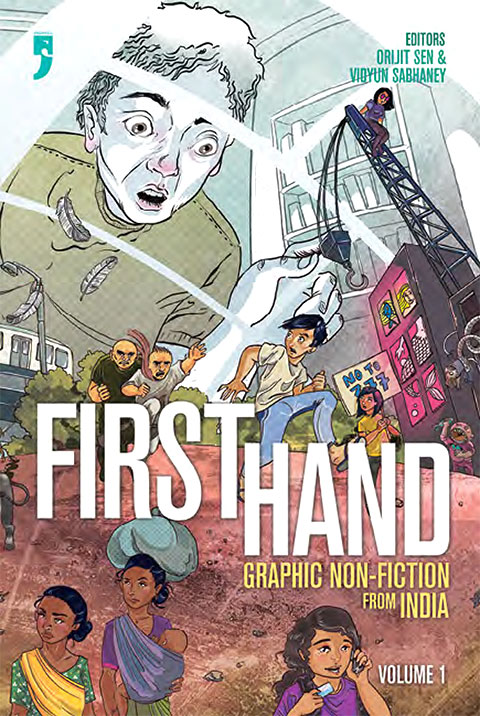

First Hand, a graphic non-fiction anthology, is a work of narrative density, comprising 22 stories from a diverse selection of researchers, journalists, filmmakers, designers, anthropologists, and academicians, which are then further presented in the six sub-genres of Oral History, Autobiography, Commentary, Reportage, Biography, and Documentary.

While these divisions may seem inherently dry, the sequential nature of the artwork provides a unique scaffolding for what are unusually perceptive narratives of the socio-political zeitgeist of modern India. The structure and pacing of the anthology is such that readers remain active and engaged through what are ostensibly subjects more often seen in academic journals. Delhi-based co-editors Vidyun Sabhaney and Orijit Sen have taken great advantage of the visual nature of the medium to present complex, challenging, and often subversive stories that are all the more vivid for having their roots in real, lived experiences.

Read on for excerpts from an interview with Vidyun Sabhaney about First Hand, nonfiction narratives, and graphic novels in India.

Vidyun Sabhaney: “Creators have to spend a lot of time building interest in the medium.”

Graphic novels are extremely liminal mediums of expression. However, there is a degree of homogenisation involved when we speak of an ‘industry’ on the creative front. What is your take on that?

I think that the field is still growing in India, and we’re quite far away from referring to it as an industry. The fact that it is largely creator-driven at the moment means that the work that is being produced is varied and content is quite dynamic—this is a very good thing. On the flip-side, creators have to spend a lot of time building interest in the medium.

Most of the storytelling in First Hand depicts characters in varying stages of rebellion, be it against systemic oppression or otherwise. Was your intention to anthologise such narratives?

There is a lot of power in illustrating real life, a lot of agency that process creates. From that perspective, anthologising narratives that address social and political injustice has been an important dimension of the editorial process of the comic book. Particularly, stories that may not make it to mainstream media, or have not been done justice in their telling, or received the kind of platform that they should. Being a visual narrative, the medium gives the sense of having seen many of these stories and their characters, first-hand. I think the knowledge that these are stories of real lives, makes the message of these stories more urgent for the reader. This is an important motivator for the project, to bring these narratives closer to the reader.

What were the criteria for selection when you went about collecting stories to compile in this volume?

For us, they needed to reflect, document, or comment on the social and political milieu of contemporary India in some way. Simply ‘nonfiction’ would not do. The quality of the scriptwriting and the artwork, of course, played a role in the selection as well.

How and why did you choose these particular authors and artists? What was the process of assimilation like?

What we did first when we began this process two years ago was to start gathering stories, and begin working with the artists to bring them to completion. In fact, we started quite small with just a handful of stories. When we realised that the number that we’ve gathered may not do justice to the scope of nonfiction, we opened it up through an application process and selected works from there as well.

From here, the process began in earnest, i.e., looking over and responding to preliminary sketches, fleshed out plots, storyboards, rough drawings, pencils, and ultimately, the final drafts of everyone’s work. We also organised talks and sessions with artists to create a more public conversation around the idea of nonfiction.

Mythology is often considered to be a way of ‘making sense’ of the worlds around us, though pinning sociological causes to myth-making can be quite reductive. For the sake of the question: what sociological purpose do graphic novels serve, especially for the reading population?

Here, we’re talking about specific situations that could change within the next six months, or even tomorrow. We can revisit First Hand a few years later and try to find out what the characters are up to—how their circumstances and ideas have changed. These are stories that are evolving as our world changes. That’s an important part of the project, for these stories to bring us closer in our understanding of each other. This understanding most often comes to us as reports, or in the form of books, but rarely as a visual story that can bring them alive with details, characters, locations, etc. Because of its ability to create time and space through images, the medium of comics has always been used to tell real experiences, incidents, and ideas, and place them within a larger context, whether they’re journalistic, historical, stories of individual and collective struggle, narratives of traumatic incidents, stories of hope, or larger social and political ideas. The medium of comics is an ideal one to do this—it allows you to move very quickly between emotionally complex inner worlds and a wider, macro perspective.

First Hand was a crowdfunded project. Such narratives are not necessarily the most popular—even the graphic novel as a medium hasn’t gained that much traction here. How receptive were audiences in India when asked for support?

I think the idea of a graphic novel is quite new to even regular readers, so from that perspective the response has been positive.

In First Hand, there are narratives amply backed by research, and even footnoting in one case. Can you comment on this practice? Does it serve to legitimise the narratives?

A key dimension of the project was to explore different kinds of nonfiction writing in comics, and understanding how research fits into comics is an important part of that. At one level, footnotes and references do legitimise the narratives, especially for those readers who are looking at them as lasting knowledge rather than stories. I think several of the contributors have made these works with a purpose in mind, and tools like references and footnotes help locate them in our history or contemporary life.

As these are ‘nonfiction’ narratives (the first attempt to compile them in this form, particularly in India), what demarcates nonfiction in the graphic novel, a medium that borrows amply from the fictional and personal?

This was a central question of our editorial process: what qualifies as nonfiction comics? It was particularly difficult to answer, because unlike film or photography, a comics creator would always have to re-create a scene in order to document it. The relationship with the work—for the comics illustrator—in the making of a fiction or nonfiction work would be similar. Both involve sitting at a desk with a pen and paper, and the task of creating a drawn reality.

For that reason, each attempt will have to evolve a different criteria. Joe Sacco, for example, uses the rules of journalistic ethics to navigate his understanding of what ‘nonfiction’ is. Art Spiegelman relied on interviews with his father for his work Maus but used ‘anthropomorphisation’ to visualise his characters, blending visual fantasy with biography.

Looking back, I think we relied on the writers’ process as a filter for this book, as well as the ‘contemporariness’ of the narratives. ‘Process’ here refers to how the material that forms the base of the narrative was gathered—for example, if it was through research, interview, or personal experience.

Is there a central thrust to First Hand, as an anthology sometimes provides? I suppose one could observe certain motifs and such; however, patterns can be enforced anywhere, hence the question.

I think for the first volume of First Hand, the thrust has been simply exploring the genre of nonfiction in India and understanding its scope and possibilities, both from a visual and scriptwriting perspective.