On a particularly sunny morning in Bandra, I woke up one day to a phone call from my mother. She and I conversed in our native language, Tamil. After a hasty breakfast, I left for a meeting. Almost at my destination, I was lost, and I asked a security guard for directions in my broken but functional Hindi. When I arrived at my meeting with Sunil Shanbag, one of Mumbai’s city’s most well known theatre veterans, we spoke in English.

As a researcher who has been studying the role of language in Indian theatre, I continue to be amazed by the number of languages most Indians speak, not least among them English. India is believed to be the world’s second-largest English-speaking country in the world, second only to the United States. Most of that English is spoken in and around urban centres. English newspapers and magazines enjoy wide circulation around the country, and contemporary English novelists such as Chetan Bhagat and Preeti Shenoy have a large readership in India.

While literature and theatre might be considered cousins by some, unlike the former, English theatre does not have as strong a foothold amongst Indian audiences. English theatre can sometimes be construed by critics as being a symptom of the “colonial hangover”—an extravagant medium that does not suit its surroundings nor its time.

Studying the role of language in theatre reveals a lot about India in a post-colonial, globalised world, fraught with many complexities and nuances. As part of my yearlong research project, I spent a month in Mumbai, watching plays and interviewing some of the many theatre practitioners in the city. What I wanted to understand was the role of language. What language did these practitioners think in, write in, and perform in? How did that influence their art and the content of their productions?

English theatre won a place for itself in India with the advent of the British East India Company in the 19th century. Colonial officers and employees of the Raj would perform plays in proscenium playhouses, often selling tickets to audience members. This was different to how theatre, typically of the Sanksrit variety in the North, was performed. As the British Raj continued to exert its influence in India, the three Presidencies, Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta, gained the most exposure to this new form of theatre, and slowly, the locals also started performing in English.

Sunil Shanbag’s Gujarati adaptation of All’s Well that Ends Well was staged at the Globe in England.

According to Sunil Shanbag, a protégé of renowned theatre director Satyadev Dubey, “What language you work in is not so important as the work you do.” In 1985, Shanbag founded Arpana, a theatre company that performs plays by both Indian and international playwrights. While Arpana continues to work mainly in Hindi theatre, the company did stage a Gujarati adaptation of Shakespeare’s All’s Well that Ends Well at The Globe in England. The choice of language, according to Shanbag, was prompted by the backing provided by the large Gujarati population in the Diaspora. “It wasn’t so much the language that mattered. It came down to the adaptation of the play to a Gujarati aesthetic, making it commercial and melodramatic,” said Shanbag.

When playwright Ramu Ramanathan wrote the play Cotton 56, Polyester 84 for Arpana, he wrote it in English. At the insistence of Shanbag, the play was translated to Hindi by Chetan Dadar, set in verse, with songs performed in Marathi. The reason, he told me, was because this play was about low-income mill workers, most of whom would not, as real people, have any command of the English language.

This amalgamation of various languages in one production is a symptom of Mumbai’s multilingual society. While Cotton 56, Polyester 84 manages to successfully consolidate its different linguistic influences, not every theatrical production in Mumbai manages to do so.

Theatre in Mumbai is diverse and eclectic. While it may seem like Gujarati, Marathi, Hindi and English productions jostle for the attention of the locals, willing them to pick their play over the various others being performed on the same day, that is not actually the case. The audience crossover between languages is not very common, and patrons usually tend to watch plays of one language. “Even venues are different,” Ramu Ramanathan told me. For instance, Gujarati plays tend to be performed at specific venues, as do Marathi or Hindi plays, with some locations providing discounted rates to plays of certain languages.

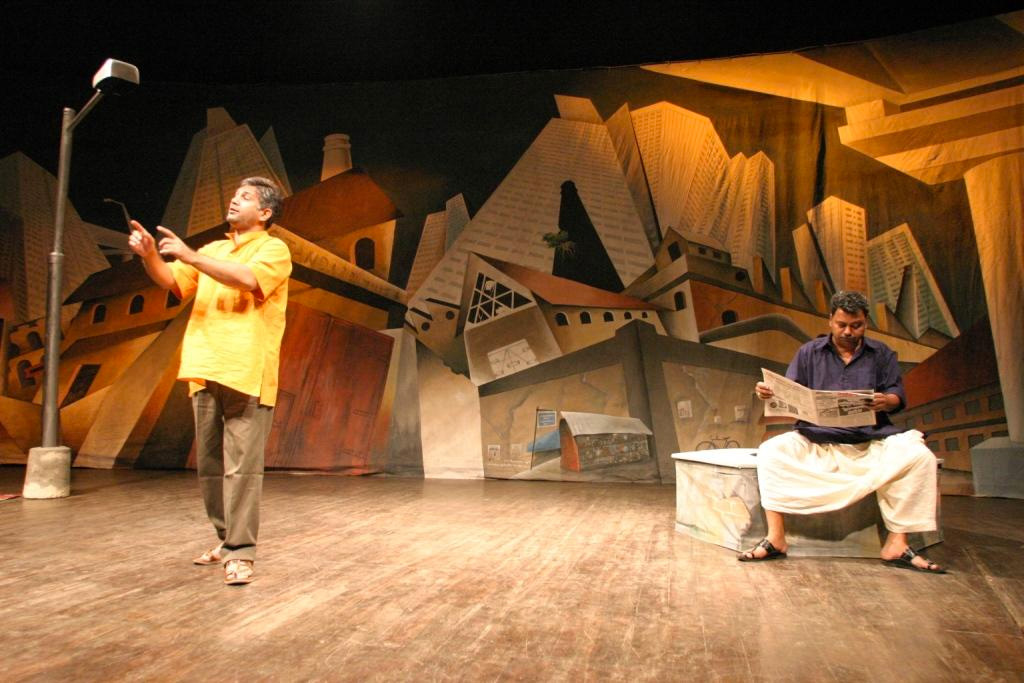

A scene from Arpana’s Cotton 56, Polyester 84. Photograph from Wikipedia.

Shernaz Patel is an actor who works in both theatre and film. She is a founding member of Rage Productions, a theatre company that organises the Writers’ Bloc festival in conjunction with the Royal Court Theatre in London. Writers’ Bloc invites playwrights from across India to participate in an 18 month workshop process, at the end of which their plays are staged at a weeks-long festival at Prithvi Theatre.

Patel, who works primarily in English theatre, is quick to point to the limitations of the language, and agrees with Shanbag that the language of the play has to be natural. “English theatre is much more urban. If you produce a play set in a village in India, and you write it in English, it just sounds weird. But, of course, if you were doing the same play in the U.K., you would have to give it a translation. And somehow, then, you transcend the fact that it’s from another country, that these characters would not be speaking this language in real life. It’s like watching Chekhov—we don’t insist that it has to be in Russian. We’re happy watching it in English, even though I’m sure in Moscow, they would much rather perform it in Russian. It’s the same thing.”

When Akash Mohimen developed his play Mahua for Writers’ Bloc in 2012, he wrote the first draft in English. The story is set in a tribal land, and tells the story of a man fighting to protect it. As he continued to write the play, Mohimen was encouraged by Patel to translate it to Hindi. Hindi, Patel told me, seemed like a more natural choice, especially considering that a man like the protagonist would probably not speak English in real life. The play was eventually performed in Hindi to positive reviews.

The issue of language is at the core of English theatre in India. Can/ should one write a play where characters speak a language that they wouldn’t speak in real life? In this post-colonial and globalised era, a generation of South Asians have grown up speaking English as their first language, and when they put pen to paper, they write in English. By doing so, are they necessarily precluding themselves from writing about certain topics and people? Does their writing alienate audiences?

Not in fiction. Indian novelists from both the Diaspora and the country are able to narrate stories about people from every corner of the country while writing in English. Even Indian plays in English performed abroad are able to transcend the scrutiny of credibility, as Shernaz Patel points out, because it is often performed to an audience that would not understand the language that the characters would originally converse in.

In her book, Theatres of Independence, Aparna Dharwadker provides an interesting explanation to this confounding issue. She suggests that Indians are more likely to read English novels by Indian authors than watch English plays by Indian playwrights because the naturalisation of English is more effective in the printed word, and not the spoken or enacted word. This is also why, Dharwadker claims, despite having the largest film industry in the world, India does not produce many English language films.

Why does this distinction in preference exist? Because language tells us so much about the structure of the world we live in. Theatre and other visual media represent a lived experience, wherein a viewer is invited to enter the world of the characters. Unlike in fiction, accents and local dialects are not left to the imagination. When those characters are from similar backgrounds as the viewer, but speak a different language, it creates a dissonant experience, and can be alienating to the viewer.

To some theatre practitioners, this means that English plays can only portray the lives of people who would speak English in their daily lives. And yet, both in India and abroad, we are happy to watch productions of Romeo and Juliet, set in Italy, with actors performing in British accents. The alienation and the dissonance tend to happen only when the subject material is close to home, literally speaking.

Up until twenty to thirty years ago, most English plays performed in India were either plays written by Western playwrights, or plays translated to English from other regional languages.

“When we started doing plays in the ’80s and ’90s,” Shernaz Patel says, “We were only doing plays from abroad. And we were happily doing it, because it was great writing. It was only in the ’90s that adaptation really began. In our first adaptation, we localised the English, and it was a huge success. That’s when we realised that this is what people identify with—talking the way they talk. We asked ourselves why we’re so burdened with western language rhythms.”

While Rage Productions still does straight, unadapted western plays (when I met Shernaz Patel, they were about to leave for Dubai to perform William Tennessee’s Glass Menagerie), they also perform English plays set in Indian settings, often written by Indian playwrights. As Patel says, “A play is a play. For me, as an actor, we want to explore some of the greatest texts that have been written with fantastic and iconic characters. But we are definitely doing a lot more local work.” While the Writers’ Bloc festival supports productions in various Indian languages, English is the overwhelmingly popular choice. The fourth Writers’ Bloc festival ended in May 2016, leaving the world of Indian-English theatre richer by a few more original plays.

Joy Sengupta and Suchitra Pillai in a scene from Dance Like a Man, directed by Lillete Dubey. Photograph by Lynn Fernandes.

Today, there is a cohort of contemporary Indian writers challenging the notion that English theatre is not ‘Indian’. Chief amongst them is Mahesh Dattani, a prolific playwright who has authored successful plays such as Dance Like a Man and Final Solutions, which have gone on to be performed around the world. Over the course of two meetings with Dattani, we spoke about his role as one of the preeminent English playwrights in the country.

In his foreword to the script of Final Solutions, Dattani writes, “I am practising theatre in an extremely imperfect world where the politics of doing theatre in English looms large over anything else one does.” After the first few performances of his play, Dance Like a Man, he received widespread criticism for his choice of language: English. It was, according to some, quite “un-Indian”.

“English as a language of communication is deeply rooted in India,” Dattani said, “because you want to make yourself competitive in the international market. However, English as a language of expression has not really taken root in India, and hasn’t changed much in the past 35 years. But it’s changing: with cultural cross-pollination and inter-community marriages, more people are speaking English with each other. It has become a very urban language, taking on the flavour of the region. How English is spoken in Mumbai is somewhat different to how it is spoken in Chennai or Calcutta. It’s almost as if English has become a regional language, where we have ‘Englishes’ rather than just one universal Indian-English.”

Depicting the lives of mostly middle-class urban Indians, Dattani is unabashed and unapologetic about his choice to write in English. He defends his writing by stating that the language of the creator (i.e., the playwright) and the language of the character do not have to meet. He writes in English because it is the language he speaks best. “Some people are okay with it, some are not,” he shrugs, with a smile on his face.

English theatre in India continues to evolve and forge an identity for itself, as Indians continue to revise their complex relationship with the language. As the capital of theatre in India, Mumbai is home to various theatre groups, both fledgling and established, who are exploring new ways in which English can be used as the language of medium. From established veteran director Alyque Padamsee, who has staged grand and opulent productions from the west such as Evita and Jesus Christ Superstar, to less renowned and more experimental theatre groups staging plays in very ‘Indian English’, this multilingual city is home to passionate artists who care about the medium of theatre and are finding and creating their own language to communicate with audiences. As Sunil Shanbag reminds us, “As Indians, our ears are accustomed to so many languages. We have to take advantage of it in the theatre that we create.”