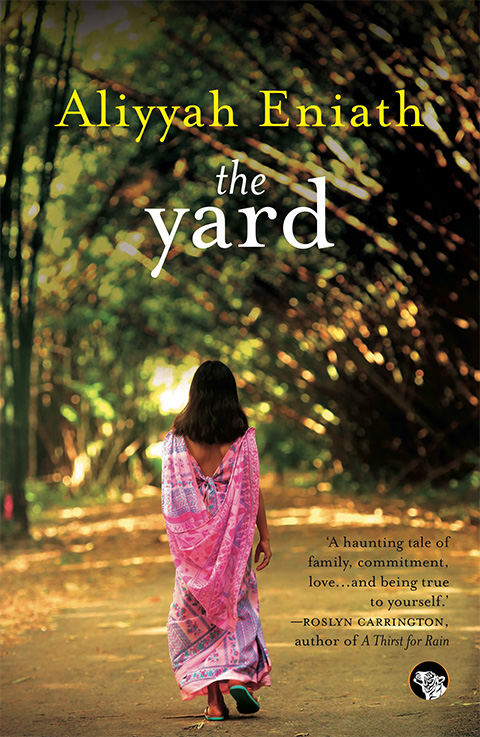

Early in Aliyyah Eniath’s debut novel The Yard, we come across “callaloo”, a quintessentially Trinidadian word, which for me is the summation of both the stylistic and narrative choices employed in this debut work of fiction. Callaloo, being a Caribbean creole word for a soup or stew made with mixed greens and crabmeat, is often used to describe a jumbled or chaotic state of affairs, and it is certainly a very strange mix that Eniath serves up to us in this book.

The Yard is the setting for the proliferous Ali clan, who are the descendants of East Indian Muslims who came over to Trinidad in the 1900s as indentured labour. According to the author, there are multiple personal experiences that wound up being fictionalised within the world of the Yard. Living together in a family compound—the eponymous Yard—the individual struggles of the various members of the family are narrated by Eniath, with the relationship between protagonists Maya and Behrooz forming the primary narrative thrust.

It begins, most surprisingly, in the tradition of the best Victorian Gothic fiction: the arrival of a strange orphan boy, Behrooz, who has no memory of his past. Behrooz is rescued and adopted as a son by a charitable father figure Khalid, who risks the possibility that under Islamic law, the boy would never be mahram and consequently free of the dangers of consanguinity to pursue his own daughters romantically.

The addition of this stranger to their close-knit and often claustrophobic family dynamic upsets several relatives, and this displeasure is vented upon Behrooz at periodic intervals throughout the narrative. He is never more keenly aware of his status as an outsider when his passion for Maya, Khalid’s second daughter, blooms uncontrollably. Despite his best efforts to redirect his attention towards Sara, a more suitable match, a rift in the family arises. Maya in particular is as capricious and self-involved as Scarlett O’Hara from Gone with the Wind, prompting a character to exclaim in exasperation at one point, “Maya, don’t you see? Not everything is about you.”

When their attraction is perceived as behaviour antithetical to the tenets of Islam, there eventually grows a multi-generational divide, with a great deal of tribulation for the thwarted lovers.

Eniath’s perspective on the rites of Islamic life in Trinidad is certainly engaging, but although she does address growing radicalisation in the perspectives of the family, there is not much consideration given to the socio-political forces working in the larger world beyond it. In that sense, the Yard is an island within an island; a deeply insular community in which some characters seek to isolate themselves further and others yearn to leave.

Maya and Behrooz both assume the role of the family prodigal at different points in the narrative, leaving and then returning; for the pull of the family seat is such that “they knew they’d been swallowed up and spit out”.

There are many parallels that can be drawn here, from the Dickensian “adopted orphan” trope to the central love story mirroring the savage and destructive magnetism between Heathcliff and Cathy in Wuthering Heights: “Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same” becomes “[…] that girl (sic) going to destroy their marriage. She’ll never get him out of her soul.” There are elements too, of the patient self-denial of Jane Eyre, another Brontëan co-relation that’s hard to overlook. Portentous dreams, sudden deaths, and high melodrama round out the tableau of their family turmoil.

These are the most incongruous parts of the book for me—there is a quality of deus ex machina in the arrival and departure of certain characters that feel particularly heavy-handed in the narrative. For instance, when Maya attempts to get even with Behrooz for pursuing Sara, a conveniently buff beau shows up for the span of a chapter. There are members of the protagonists’ immediate family that never get more than a few lines of dialogue and then are conveniently sent away abroad for the remainder of the book.

It’s instances like these that make one wonder whether Eniath might not have been better served by judicious editing. Casual readers might not notice the many strained sentences that are scattered throughout the book, but it was a trial for this reviewer to read phrases such as “he crashed his lips against hers” and “she watched him get into his car and dissolve”.

Elsewhere one encounters errors such as the inability to differentiate between blond and blonde and euphemisms such as “Maya released her anxiety on the cabin floor”. (She vomits.)

Where The Yard does work, is in its intimate descriptions of family life and how race, place and religion factor into the emotional decisions made by the characters. Eniath works in a few poignant details of the travails of parenthood that are particularly vivid: Sara struggles with post-partum depression and emotional dissociation from her marriage and children. In a culture where being a mother is considered a supreme virtue, she visibly struggles with the role, while Behrooz assumes the mantle of gentle, involved father with quiet ease, willing to do whatever it takes to keep his marriage intact.

Bereavement, grief, and mourning are also the background for some affecting scenes, where funerals are seen from the perspective of the women excluded from the rites of burial itself. It is difficult to say the same for the many weddings that feature in the book, one of which has a bizarre description of the family at a bridal shower moulding penises out of plasticine. Wherever Eniath gives us the native patois spoken by some of the members of the older generation, the dialogue roars back to life from the platitudes it is riddled with most of the time.

Most of what happens in The Yard will be deeply familiar to readers that have grown up in a large joint family themselves, and it is for them that this book will be most rewarding. The delicate negotiations of respect and taboo remain the same whether in India or Trinidad, even down to the casual misogyny that prompts an attempted honour killing. Themes of sexism and prejudice, it seems, are truly universal, even separated by the distance of half a world.

Ultimately, where The Yard succeeds, is in becoming the fictional personification of what Derek Walcott describes in his Nobel lecture, that “there are still cherishable places, little valleys that do not echo with ideas, a simplicity of rebeginnings, not yet corrupted by the dangers of change. Not nostalgic sites but occluded sanctities as common and simple as their sunlight.”

[ISBN 9789385755088; Speaking Tiger Books]