Most of us know Nilanjana Roy from her compelling essays on writing and gender, and her novels about imaginary cats in an old neighbourhood of Delhi. Her first book, The Wildings (2012), about a fearless band of cats in Nizamuddin, won the Shakti Bhatt First Book Prize and became a critically acclaimed bestseller. Its sequel, The Hundred Names of Darkness, released in 2013 to positive reviews.

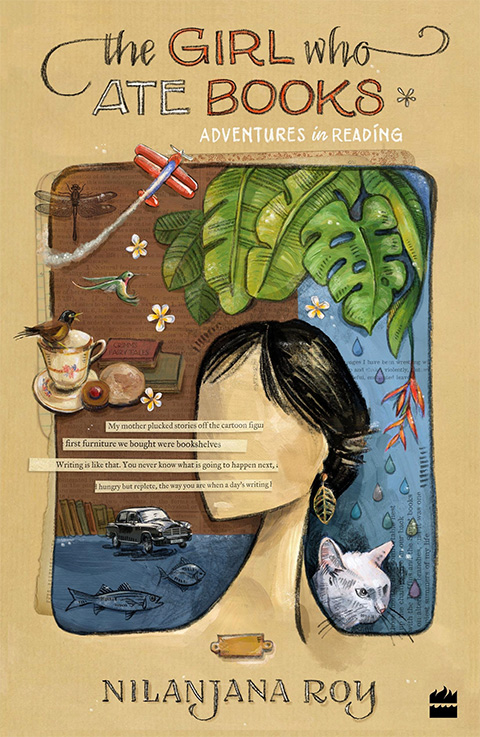

A little over a month ago, she brought together two decades of essays and interviews on Indian writing in English in The Girl Who Ate Books. Few critics have paid attention to the lives, dilemmas, and influences of Indian writers in the way that Nilanjana Roy has. Her work is accessible and sympathetic rather than academic, and she makes a point of noting that her book is far from a comprehensive history, but instead a personal chronicle of reading in Delhi and Kolkata.

In this exclusive interview, we speak to her about the process of writing, traditions, final drafts, and the tragic side of plagiarism.

“Sometimes you write out of empathy, but sometimes you write to try to grasp something that is completely foreign to your experience.” Photograph by Kavi Bhansali.

When the girl who ate books was growing up, was this the kind of book she envisioned herself writing?

I imagined reading and travelling, and tried to figure out adult-world jobs that would let me do both, but it was only in my late thirties that I realised writing was a possibility. I’d thought there was a permit system for writers: you had to be really good or the people at The Bureau For Licensing of Writers wouldn’t stamp your papers. It was a great relief to belatedly discover that I could just go off and write about imaginary cats, or write a thank-you letter to authors and books. That’s what The Girl Who Ate Books is: a very long thank-you note.

There is a particularly striking image in the book of a continuous taar between the old writing and the new. As a journalist who has paid close attention to Indian writers for two decades in the form of reviews, interviews, and essays, would you say there were writers or traditions you were following in these writings?

We all are, even when we don’t know we’re mirroring someone from the past. Awadh Punch’s satire

reminds me of All India Bakchod and the stand-up comedy scene today. The work that Amit Chaudhuri, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, and Ira Pande, for instance, do as critics and translators is a continuation of the work of recovering and celebrating our common history across Indian languages that was so important to 19th century Indians. I write unconsciously in the manner of the 18th and 19th century Indian editors who mixed political and social commentary with their booklove. It feels good to claim kinship in retrospect, to be part of the same family that includes the eccentric editor of Mookerjee’s Magazine or Rokeya Begum’s spirited polemics, for instance.

In the prologue to the book, you acknowledge that your homage to books in India is focused on two cities and two languages. You invite writers from across the country to write their own memoirs of reading in other parts of India. It conjured up the image of a map with a dot for every place whose unique reading experience had been written about. Would you say this book is a dot on the map?

Two tiny dots, Delhi and Calcutta. And even there—my experience of reading in 1970s-1980s South Delhi would not be the same as a reader growing up in 1990s West Delhi borrowing books from the Anaj Mandi public library. Writers on writing is still a very Western genre—even in India, it’s the Indian writer in English who’s interviewed about their writing lives, far more often than writers from all of India’s other languages. I would love to see that change and see many more dots on that map.

Nilanjana Roy’s The Girl Who Ate Books (Purchase)

Nilanjana Roy’s The Girl Who Ate Books (Purchase)It was interesting to me that you mentioned the multiple years in which some essays had been written. It felt like you removed a wall between the work itself and the process, and challenged the idea of a final draft. What drove you to include the years at the end of each piece?

My editor, Somak Ghoshal, suggested that we should include a rough chronology. The essays in The Girl Who Ate Books had grown out of columns that were written for the moment, and I hadn’t realised how often I’d gone back to an event in literary history, or to a particular writer’s story, sometimes returning after years. It seemed more honest to let readers see the slow discoveries, the gradual and often humbling realisation that I knew so little about my own country’s literary history, than to pretend that each essay came forth perfectly formed.

I read like a curious, open-minded amateur, not with a scholar’s expertise and focus. I’m not big on final drafts. Some writers are meticulous perfectionists—think of Coetzee’s 19 drafts—and I respect that, but I probably write more the way an artist doodles: you explore themes over a series, and you might come back and doodle some more years later. Agha Shahid Ali’s poem Rooms Are Never Finished is up on my wall as an artist’s credo of sorts. Books are never finished, either.

What drew you to the stories of plagiarism? When you imagine Indrani Aikath Gyaltsen writing in the hills, copying page after page of another author’s book—it made me view plagiarism differently.

These are such sad stories, the plagiarism ones, aren’t they? I think they helped me understand an anxiety I would otherwise have had no insight into: the fear, terrifying for some writers, that they will never be seen or given public recognition. I have other fears—the constant nagging worry that the writing is not good enough, the anxiety that comes from feeling I don’t know the worlds of Bengali, or Hindi, or Persian literature as well as I should—but I don’t understand how someone might fear invisibility so much that they would actually steal another writer’s work rather than leave an empty space. That vulnerability is so human, and so tragic. Sometimes you write out of empathy, but sometimes you write to try to grasp something that is completely foreign to your experience, and that was the root of the three plagiarism essays.

You say, at more point that one, that words matter more than the paper they are on. At another juncture in the book, you talk of cheap paperbacks published in Kolkata where the pages were so thin you could read two pages at once. Could you tell us more about your relationship with paper?

You don’t have to eat books to know that the first relationship we have with books and writing is tactile. I read on the Kindle as well, and it’s profoundly dislocating. E-reading keeps the writer’s voice intact, just as sharp or as murmuring as it is on the page, but you lose your sense of geography, and I lose my ability to hold a “map” of the book in my head. Briefly: paper matters to me. I don’t fetishise books as objects, but a well-made book is like a well-made meal, and bookfeel can be as pleasurable as mouthfeel.

You have interviewed writers from Kamala Das to Jeet Thayil, from Agha Shahid Ali to Vikram Seth. Who else would you interview, if you could?

Andal, the women of the Therigatha, Sei Shonagon, Harper Lee. (I assume you’re not anti-dead-writers.)

How does having books published affect your relationship with writing?

It’s changed the way I read. Three books in, I am very slowly learning craft, voice, technique. I read other writers now with an acquisitive hunger that feels different from the previous two decades of reading for pleasure or for information.

Writing is a lot like photography or art in that it teaches you to slow down, to pay attention to what you understand about the world, to what you don’t understand and find compelling anyway, and to claim what you love. I didn’t plan to write books about cities, ambiguity, empathy, writers, the secret lives of cats and cheels, but it turns out that’s what I was paying attention to most all these years. These are not large or grand subjects, but they were unexpectedly rich territory, very satisfying to explore.

What are you working on at the moment?

A big untidy sprawling crime thriller set in the Delhi and Haryana of the 1970s and 1980s. I always wanted to write a book that managed to link buffaloes, corpses, baroque farmhouses and revolutionary poets, and this is my chance.

———

Click here to purchase The Girl Who Ate Books.